The 911 operator heard panic in his voice.

“She’s still breathing,” Michael Peterson gasped into the phone at 2:40 that December morning. “Please hurry. There’s been an accident.”

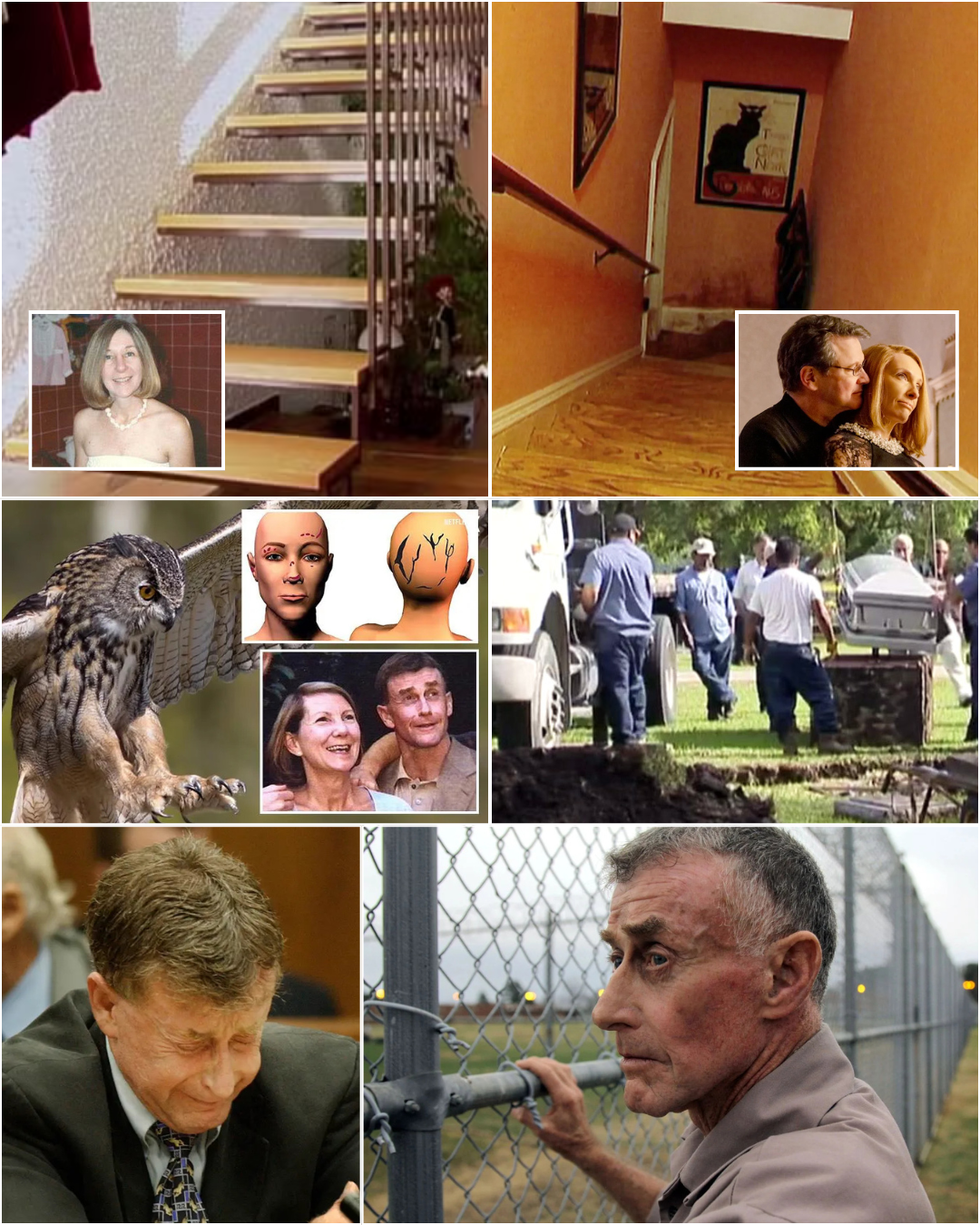

But by the time paramedics reached the mansion on Cedar Street in Durham, North Carolina, Kathleen Peterson was gone. She lay at the bottom of the back staircase, forty-eight years old, her body motionless.

What the first responders saw that night would haunt them for years. What investigators would uncover in the months that followed would tear a family apart and launch one of America’s most bewildering legal battles—a case that, more than two decades later, still has no definitive answer.

Because the question that December night wasn’t just how Kathleen died.

It was whether anyone could ever truly know.

The Woman Who Had Everything

Kathleen Hunt Atwater didn’t just break barriers. She shattered them before most people even knew the barriers existed.

In 1971, Duke University’s School of Engineering had never admitted a woman. Not one. Kathleen walked through those doors anyway, the first female student they couldn’t say no to. She was brilliant, driven, the kind of person who made excellence look effortless.

By 2001, she was pulling in $145,000 a year as an executive at Nortel Networks. She sat on Durham’s Arts Council board. She hosted elaborate dinner parties where conversation flowed as freely as the wine. Friends described her as magnetic—someone who made you feel like the most interesting person in the room.

Her home was a testament to success. A sprawling $1.4 million mansion in Forest Hills, Durham’s most prestigious neighborhood. Fourteen rooms. A pool. Surrounded by woods that seemed to swallow the city noise.

But houses, no matter how beautiful, can’t hold secrets forever.

The Blended Family

Michael Peterson had charm. The kind that made people lean in when he spoke.

A decorated Vietnam veteran. A novelist whose books drew from his wartime experiences. At sixty-three, he carried himself with the confidence of someone who’d lived multiple lives.

He and Kathleen had married in 1997, both on their second attempt at forever. They brought complicated histories to the altar.

Michael’s two sons, Clayton and Todd, from his first marriage to Patricia. Kathleen’s daughter Caitlin from her previous husband, Fred Atwater. And then there were Margaret and Martha Ratliff—two young women Michael had adopted years earlier after a tragedy in Germany.

Five children. Two parents. One household that friends described as chaotic in the best possible way.

Laughter. Wine-soaked conversations that stretched past midnight. A family that had been broken in different ways, now trying to be whole together.

Or at least, that’s what everyone saw.

The Night of December 9, 2001

They were celebrating.

Michael’s latest manuscript—a World War II thriller—had caught Hollywood’s attention. A studio was interested. After years of struggling to make his writing career profitable, this felt like vindication.

Kathleen had come home from work exhausted. It was Sunday evening, and she had emails waiting, a conference call looming on Monday morning. But Michael had champagne. The night was cold for December, but they sat by the pool anyway, bundled in jackets, talking about what a movie deal might mean.

Maybe the financial pressure would ease. Maybe the credit card debt—which had crept past $140,000—would stop feeling so suffocating. Maybe Kathleen wouldn’t have to worry about the layoffs happening at Nortel, the whispers that her job might not be safe much longer.

For a few hours that night, none of it mattered.

Around two in the morning, Kathleen stood up. “I need to sleep,” she told Michael. “Work tomorrow.”

She kissed him goodnight and walked into the house, her flip-flops slapping against the stone path.

Michael said he stayed outside. Finishing his wine. Smoking his pipe. Watching the illuminated water ripple in the December wind.

That was his story.

Forty minutes later, he was screaming into a phone that his wife had fallen down the stairs.

What They Found

The scene didn’t make sense.

Kathleen lay at the bottom of the narrow back staircase, the one that led from the kitchen to the second floor. Her body was still. The injuries visible even to untrained eyes.

But it was everything else that made the paramedics stop.

The staircase looked wrong. The walls showed impact patterns. The steps had smears and drops. Even the doorframe bore marks that didn’t align with a simple fall.

One of the paramedics would later tell investigators he’d worked emergency response for twenty years. He’d seen falls. Car accidents. Industrial injuries. He’d never seen anything like this from someone tumbling down stairs.

Michael stood in the foyer. His shorts bore stains. His bare feet tracked prints across the hardwood. But his demeanor struck the first responders as oddly controlled for someone whose wife had just died.

“I was outside by the pool,” he explained. “I came in and found her. I tried to help her. I called you right away.”

It sounded plausible. Tragic accident. Woman slips on steep stairs. Hits her head. Terrible, but these things happen.

The medical examiner would later tell a different story.

The Autopsy

Dr. Deborah Radisch had performed hundreds of autopsies. She knew how to read what bodies couldn’t say.

Kathleen Peterson’s injuries told a story, but it wasn’t the one Michael had described.

Seven lacerations on the back of her head. Deep. Distinct. Each one parallel to the others in a way that falls don’t usually create. Her scalp had been penetrated multiple times, but her skull—remarkably—wasn’t fractured.

That detail bothered Radisch. People who fall down stairs hard enough to cause that kind of bleeding usually have broken bones. Shattered skulls. Catastrophic trauma to other parts of the body.

Kathleen had defensive wounds on her hands. Bruising on her arms. Marks on her face and neck that suggested a struggle.

And then there was the time factor. The scene suggested she’d been upright and moving for an extended period while injured. Her heart had been pumping. The evidence indicated this hadn’t been quick.

On December 20, 2001, eleven days after Kathleen’s death, Durham police arrested Michael Peterson.

The charge: first-degree murder.

The Man Behind the Mask

Search warrants revealed what Michael had been hiding.

His computer contained years of communications. Emails to male escorts. Arrangements for meetings. Photographs. Evidence of a life Kathleen—and everyone else in their circle—knew nothing about.

Michael Peterson was bisexual. He’d been maintaining relationships with men throughout his marriage to Kathleen, meeting escorts in hotel rooms, paying for encounters that he’d carefully concealed from his family.

The revelation detonated through Durham’s social scene.

Prosecutors seized on it immediately. Their theory came together: Kathleen had discovered her husband’s secret that December night. Maybe she’d opened an email she wasn’t supposed to see. Maybe Michael’s phone had buzzed with a message. Whatever the trigger, she’d confronted him.

The champagne celebration had turned into something else. An argument. A fight that escalated until Michael couldn’t let her walk away.

At trial, the testimony was devastating. A male escort named Brad took the stand and described his encounters with Michael in clinical detail. Hotel rooms. Cash payments. A relationship that had continued right up until the week before Kathleen died.

Michael’s children sat in the courtroom and learned about their father’s hidden life in front of television cameras and a packed gallery.

His defense attorney, David Rudolf, argued that sexual orientation was irrelevant. That the prosecution was engaging in prejudice. That bisexuality didn’t make someone a murderer.

But the damage was done. Michael’s secret life had been exposed. And prosecutors now had a motive.

If Kathleen had threatened to leave, Michael stood to lose everything. The house. His reputation. His comfortable existence funded by Kathleen’s six-figure salary.

Unless she died first.

The Ghost From Germany

But there was another secret. One even more chilling.

Sixteen years before Kathleen’s death, Michael Peterson had been living in West Germany with his first wife, Patricia. They’d become close friends with another couple—George and Elizabeth Ratliff.

The two families were inseparable. Their children played together. They celebrated holidays at each other’s homes. When George Ratliff died suddenly of a heart condition in 1983, Michael stepped in to help Elizabeth, now a widow with two small daughters.

On November 25, 1985, Elizabeth Ratliff was found at the bottom of the staircase in her German home.

She’d been alone with her young daughters that night. Michael Peterson was the last adult to see her alive. He’d been at her house earlier that evening, helping her put the girls to bed.

German authorities ruled it an accident. A cerebral hemorrhage that caused her to collapse and fall down the stairs. Tragic, but not suspicious.

Michael became the legal guardian of Elizabeth’s daughters, Margaret and Martha. He brought them back to the United States, adopted them, and raised them as his own children.

For sixteen years, Elizabeth Ratliff’s death remained a footnote. A sad story that had shaped the Peterson family but raised no questions.

Until prosecutors in Durham learned about it.

The Exhumation

In April 2003, Elizabeth Ratliff’s body was exhumed from her grave in Texas.

Dr. Deborah Radisch—the same examiner who’d autopsied Kathleen—performed a second examination of Elizabeth’s remains nearly two decades after her death.

The findings were shocking.

Elizabeth’s head injuries were almost identical to Kathleen’s. Multiple lacerations. The same pattern of trauma. The same absence of skull fracture. The German investigation had missed it—or simply hadn’t looked hard enough.

Elizabeth Ratliff hadn’t died from a cerebral hemorrhage and a fall, Radisch concluded. She’d been struck repeatedly on the head. She’d been murdered.

The prosecution’s case suddenly had a terrifying symmetry.

Two women. Two staircases. Two deaths ruled accidents, then reconsidered as homicides. Sixteen years and thousands of miles apart.

And Michael Peterson was the last person to see both women alive.

The judge ruled that evidence about Elizabeth’s death could be presented at Michael’s trial. The jury would hear about both cases and decide: Was this the most unlikely coincidence in modern criminal history? Or was it a pattern of violence that Michael had gotten away with once before?

The Trial

The summer of 2003 brought national attention to Durham.

Court TV set up cameras. Reporters from across the country descended on the courthouse. The trial stretched across three months, every day revealing new details that made the case more complicated, not less.

Prosecutor Jim Hardin presented what seemed like an overwhelming case.

The autopsy evidence. The blood patterns at the scene. Michael’s hidden life and the motive it provided. The financial pressures—Kathleen’s company was failing, layoffs were coming, they were drowning in debt. The life insurance policy worth $1.4 million that Michael would collect if Kathleen died.

And then there was Elizabeth Ratliff. The jury heard about the German staircase. The identical injuries. The adoption of her daughters. The eerie repetition of circumstances.

The prosecution’s portrait of Michael Peterson was damning. A desperate man. A skilled manipulator. Someone who’d killed before and believed he could kill again.

David Rudolf, Michael’s defense attorney, fought back with experts who challenged every piece of evidence.

The scene was consistent with a fall, they argued. Kathleen had been drinking. The stairs were steep. She’d slipped, hit her head, tried to stand, fallen again. The extended time frame explained why there was so much evidence at the scene—she’d been conscious and moving for a while before she died.

The lack of skull fracture actually supported the accident theory, defense experts testified. A beating would have shattered bone. These were injuries from impacts against wood, not from a weapon.

And Michael’s bisexuality? His hidden relationships? Irrelevant character assassination by a prosecution that couldn’t prove their case with facts.

Michael’s children testified for their father. All five of them, including Kathleen’s daughter Caitlin, stood before the jury and said the same thing: Michael Peterson was gentle, loving, incapable of violence. He’d adored Kathleen. He was devastated by her death.

But as the trial wore on, something shifted.

Caitlin Atwater sat through testimony about her mother’s injuries. She looked at crime scene photographs. She listened to experts describe what had happened in that staircase.

The accident story her stepfather had told her stopped making sense.

The Verdict

October 10, 2003.

After four days of deliberation, the jury returned their verdict.

Guilty of first-degree murder.

The courtroom reaction split along family lines. Clayton and Todd Peterson collapsed into each other. Margaret and Martha Ratliff sobbed. They couldn’t believe this was happening to the man who’d raised them, who’d been there for them after their own mother died.

But Caitlin Atwater sat still. She’d stopped believing her stepfather weeks earlier. For her, this was justice.

Judge Orlando Hudson sentenced Michael Peterson to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

As deputies led him out in handcuffs, Michael turned to his family one last time. His lips formed words: “I’m innocent.”

The story should have ended there.

It didn’t.

Eight Years Behind Bars

Michael Peterson refused to accept his fate.

From his prison cell, he maintained his innocence in letters to family, to journalists, to anyone who would listen. David Rudolf continued working on appeals, convinced the conviction had been built on flawed science and prejudice.

Michael’s sons visited regularly. So did Margaret and Martha, though they struggled with questions about their biological mother’s death that they could never fully answer.

Caitlin Atwater never came. She’d severed all ties with the man she’d once called Dad.

The years passed slowly. Michael aged in a North Carolina prison, his appeals rejected again and again.

Then, in 2011, everything changed.

The North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation became embroiled in a scandal that would shake hundreds of cases across the state.

An internal audit revealed that Duane Deaver—one of their senior forensic analysts—had been lying for years. He’d misrepresented his credentials. Fabricated evidence. Provided misleading testimony in case after case.

Deaver had been a star witness in Michael Peterson’s trial. His testimony about the scene at the Peterson home had been central to the conviction. He’d told the jury with absolute certainty that the evidence could only indicate murder, that an accident was impossible.

But Deaver’s credentials were fake. His experiments were poorly documented. His conclusions were based on methods he didn’t fully understand.

Defense attorneys across North Carolina began reviewing every case Deaver had touched.

Michael Peterson’s conviction was near the top of the list.

Freedom, Conditional

December 16, 2011.

After eight years in prison, Michael Peterson walked through the gates a free man—sort of.

A judge had granted him a new trial based on the Deaver scandal. But Michael wasn’t exonerated. He was released on bail, fitted with an ankle monitor, and told to wait while prosecutors decided whether to retry him.

He returned to Durham. Not to the mansion on Cedar Street—that had been sold years ago to pay legal bills. But he stayed in the area, living quietly while his case hung in limbo.

The prosecution insisted they would retry him. They believed in their case, Deaver’s testimony notwithstanding. They still had the autopsy. The financial motive. The secret life. Elizabeth Ratliff.

But as months turned into years, their confidence began to crack.

Key witnesses had died. Evidence had been in storage for over a decade. The cost of another trial would be staggering—millions of dollars for a case that was no longer the slam dunk it had seemed in 2003.

And then there was the problem of the owl.

The Theory No One Saw Coming

Larry Pollard couldn’t stop thinking about the photographs.

He was a lawyer, a neighbor of the Petersons, someone who’d followed the case closely. But he was also a nature enthusiast, someone who’d spent years studying the wildlife in Durham’s wooded neighborhoods.

After Michael’s conviction, Pollard had obtained copies of the autopsy photos. Something about Kathleen’s injuries bothered him. They didn’t look like hammer wounds. They didn’t look like impacts from falling.

The lacerations on her scalp were too precise. Three parallel gashes, evenly spaced. Deep and clean. And then another set, slightly offset from the first.

Once Pollard saw the pattern, he couldn’t unsee it.

Those weren’t weapon marks. They were talon marks.

He began researching barred owls, a species common throughout North Carolina. The birds were territorial, aggressive, especially during nesting season. And they’d been documented attacking humans with increasing frequency in recent years.

The attacks followed a pattern. Silent swoops from above. Talons targeting the head and face. Victims often had no warning until they felt the strike.

Pollard’s theory came together piece by piece.

The Peterson property backed up to dense woods where barred owls nested. Kathleen had been outside by the pool that December night, her blonde hair potentially visible in the darkness. If an owl had attacked her as she walked back to the house, it would explain the injuries that had baffled everyone.

The talon-shaped lacerations. The defensive wounds on her hands as she tried to fight off the bird. The lack of skull fracture—owl talons penetrate skin and muscle but don’t break bone. The pine needles and tiny feathers that had been found in Kathleen’s hands, noted in the autopsy report but never explained.

Pollard theorized that Kathleen had been attacked outside, stumbled into the house bleeding and disoriented, and then collapsed on the stairs. In her confusion and pain, she’d tried to stand multiple times, striking her head on the wooden steps and doorframe, creating the scene that investigators had interpreted as evidence of murder.

It sounded absurd. Like something from a dark comedy rather than a serious legal defense.

But when ornithologists examined the theory, they couldn’t dismiss it.

Barred owl attacks matching this description had been documented. The talons were sharp enough to cause the injuries Kathleen had sustained. The bird’s behavior—territorial aggression toward perceived threats near nesting areas—fit the circumstances.

Dr. Deborah Radisch, the medical examiner who’d been so certain about murder, was asked to review the owl theory. She couldn’t conclusively disprove it.

Neither could prosecutors.

And that became their nightmare.

Reasonable Doubt

By 2016, the case had been in limbo for five years.

Michael Peterson was still living under house arrest, his ankle monitor tracking his every movement. He’d turned seventy-two. The man who’d once hosted elaborate dinner parties and traveled the world was confined to a small radius in Durham, waiting for a decision about whether he’d spend the rest of his life in prison.

The prosecution knew they were in trouble.

If they retried Michael and his defense team presented the owl theory, they’d create reasonable doubt. The jury wouldn’t have to believe an owl had killed Kathleen—they’d only have to believe it was possible. And possibility was enough for acquittal.

The defense had another advantage now, too. Duane Deaver’s discredited testimony meant the blood spatter evidence—the foundation of the original conviction—was worthless. Without that, what did prosecutors really have?

A secret life that didn’t prove murder. Financial troubles that millions of Americans faced without killing their spouses. And Elizabeth Ratliff, whose death had happened so long ago in another country that proving anything about it now was nearly impossible.

In early 2017, both sides began discussing a compromise.

The Alford Plea

February 24, 2017.

The courtroom was packed again, but this time there would be no trial.

Michael Peterson stood before the judge and entered an Alford plea to voluntary manslaughter.

It’s a peculiar legal mechanism, the Alford plea. It allows someone to maintain their innocence while acknowledging that prosecutors have enough evidence to likely secure a conviction. The defendant doesn’t admit guilt—only that fighting might result in a worse outcome.

For Michael, it was the least bad option on the table.

He didn’t admit to killing Kathleen. He simply acknowledged that if the case went to trial again, a jury might convict him, and he wasn’t willing to risk another life sentence for a crime he insisted he didn’t commit.

The judge sentenced him to time served—the eight years he’d already spent in prison, plus credit for the five years under house arrest.

Michael removed his ankle monitor in the courtroom. After sixteen years of legal battle—incarceration, house arrest, and limbo—he was finally, completely free.

He hugged his sons. Embraced Margaret and Martha. Walked out into the February afternoon.

“I’ve maintained my innocence from the beginning,” he told reporters on the courthouse steps. His voice was steady but tired. “This doesn’t change that. But I’m an old man. I want what’s left of my life back.”

Caitlin Atwater wasn’t there. She’d released a statement through her attorney saying the plea changed nothing. Her stepfather had murdered her mother, and no legal technicality would alter that truth in her mind.

The Peterson family remained fractured. Some believed Michael. Some didn’t. The case that had dominated their lives for sixteen years was over, but the damage would last forever.

The Unanswered Questions

What really happened on the staircase at 1810 Cedar Street?

After two trials, countless expert witnesses, documentaries watched by millions, and legal proceedings that stretched across sixteen years, America is no closer to a definitive answer than it was that December morning in 2001.

The evidence is contradictory. The theories range from plausible to bizarre. And the only two people who know with certainty what occurred that night are Kathleen Peterson—who’s been dead for over two decades—and Michael Peterson, who has never changed his story.

Consider what we know for certain.

Two women died at the bottom of staircases sixteen years and thousands of miles apart. Both deaths involved significant head trauma. Both were initially ruled accidents before being reconsidered as potential homicides. Both women knew Michael Peterson intimately. And in both cases, Michael was the last person to see them alive.

Is that coincidence? The kind of astronomical bad luck that defies probability? Or is it a pattern—evidence of something darker that Michael has hidden behind respectability and charm for decades?

The answer depends entirely on which narrative you choose to believe.

The Case for Murder

Those who believe Michael is guilty point to a compelling collection of circumstances.

The injuries to Kathleen’s head don’t match typical fall patterns. The scene was too violent, too extensive for an accident. Michael’s calm demeanor when first responders arrived struck many as inappropriate for someone who’d just lost their wife.

His hidden life with male escorts provided motive. If Kathleen had discovered his secret that night and threatened divorce, Michael faced financial ruin. Kathleen’s salary funded their lifestyle. Her death meant $1.4 million in life insurance. Simple, ugly math.

The Elizabeth Ratliff connection is impossible to ignore for this camp. Two identical deaths separated by sixteen years, both involving Michael? That’s not bad luck. That’s a pattern.

And Michael’s behavior after Kathleen’s death raised eyebrows. He began a relationship with Sophie Brunet, a French documentary editor who was working on a film about his case. They exchanged letters while he was in prison, then began dating after his release. Some saw this as a man moving on. Others saw it as someone who’d never truly loved his wife.

For Caitlin Atwater and those who agree with her, the evidence is overwhelming. Her stepfather murdered her mother. The justice system failed to keep him in prison. That’s the truth she lives with every day.

The Case for Innocence

Michael’s defenders see a different story.

A man who loved his wife found her after a tragic accident. In his panic and grief, he tried to help her, contaminating the scene in ways that later looked suspicious. The blood patterns that convicted him were interpreted by a discredited analyst who’d lied about his credentials for years.

The lack of skull fracture is significant to this camp. Someone beating another person hard enough to cause seven deep lacerations would almost certainly break bone. Kathleen’s skull was intact. That suggests falls, not strikes from a weapon.

Michael’s secret relationships with men were private matters that had nothing to do with whether he killed his wife. The prosecution weaponized his sexuality, engaging in prejudice to paint him as deceptive and dangerous. Bisexuality doesn’t make someone a murderer.

As for Elizabeth Ratliff, her death happened eighteen years before Kathleen’s. German authorities investigated and found no evidence of foul play. The later exhumation and reexamination happened in the context of Michael’s trial, with American prosecutors looking for anything that would support their case. Coincidences do happen. Tragic ones, but coincidences nonetheless.

Michael’s sons, Clayton and Todd, have never wavered in their belief in their father’s innocence. They’ve stood by him through everything. That loyalty, his defenders argue, means something.

The Case for the Owl

And then there’s the third possibility, the one that seems too strange to be real but can’t be definitively disproven.

What if Kathleen Peterson’s death wasn’t murder or a simple accident? What if it was something no one had considered because it seemed too bizarre?

The owl theory has scientific support that’s hard to dismiss. The talon patterns match. Barred owl attacks on humans have been documented, including cases where people suffered serious head injuries. The birds hunt at night, targeting the head, and their strikes are silent.

Pine needles and microscopic feathers were found in Kathleen’s hands and hair. The autopsy noted these but offered no explanation. An owl attack would explain them instantly.

The lack of skull fracture fits this theory perfectly. Owl talons are sharp—they penetrate but don’t fracture bone the way blunt force trauma would.

And Kathleen’s behavior after the alleged attack makes sense if she’d been disoriented and bleeding. Stumbling inside, collapsing on the stairs, trying repeatedly to stand, striking her head on the wooden surfaces each time. It explains the extended time frame, the multiple impact sites, the blood patterns.

Ornithologists who’ve reviewed the evidence say it’s plausible. They can’t prove an owl attacked Kathleen Peterson that night. But they can’t rule it out, either.

For some, this theory offers the only explanation that fits all the evidence without requiring Michael to be either a murderer or impossibly unlucky.

Where They Are Now

Michael Peterson is eighty-one years old as of 2024.

He still lives in Durham, not far from the home where Kathleen died. He gives occasional interviews, always maintaining his innocence. He participates in documentaries and true crime discussions about his case, his voice steady as he recounts the story he’s told for over two decades.

The Cedar Street mansion has changed hands multiple times. New owners have renovated extensively. The staircase where Kathleen died has been rebuilt. The house is just a house now, its history known but not haunting the current residents.

Clayton and Todd Peterson remain close to their father. They’ve never doubted him. The trial, the conviction, the years in prison—they believe all of it was a miscarriage of justice.

Margaret and Martha Ratliff have been more private. They were children when their biological mother died in Germany. Michael raised them from ages two and four. Questions about Elizabeth Ratliff’s death have shadowed their entire adult lives, and they’ve chosen to stay largely out of the public eye.

Caitlin Atwater has never reconciled with Michael. She filed a wrongful death lawsuit against him in 2003 and won a $25 million judgment, though she’s never collected most of it. She believes her stepfather murdered her mother. Nothing that’s happened since has changed her mind.

Sophie Brunet, the documentary editor who began a relationship with Michael while he was in prison, eventually ended things. They dated for several years after his release, but the relationship didn’t last. Michael is currently single.

David Rudolf, Michael’s defense attorney, went on to become one of America’s most prominent criminal defense lawyers. He still speaks about the Peterson case, using it as an example of how faulty forensic science can lead to wrongful convictions.

Dr. Deborah Radisch still serves as North Carolina’s chief medical examiner. She stands by her conclusions about Kathleen’s death while acknowledging that not everyone agrees with her interpretation of the evidence.

The Documentary That Changed Everything

The Peterson case became famous not just because of the bizarre circumstances, but because of unprecedented access.

French filmmaker Jean-Xavier de Lestrade began documenting Michael’s case in 2001, shortly after the arrest. He was granted remarkable access—to the defense team’s strategy sessions, to Michael himself, to the family’s most private moments.

The resulting documentary, “The Staircase,” premiered in 2004 and became a sensation. Eight episodes following Michael from arrest through conviction, showing the legal process in intimate detail rarely captured on film.

Netflix acquired the series in 2018, introducing it to a massive new audience. De Lestrade filmed additional episodes covering Michael’s release and the Alford plea, extending the story through 2017.

The documentary changed how millions of people viewed the case. Watching Michael in his own words, seeing his children’s anguish, observing the defense team’s struggles—it humanized everyone involved in ways that news coverage never could.

It also revealed the relationship between Michael and Sophie Brunet, the editor working on the film. Their correspondence began while he was in prison. Romance bloomed during her visits. Critics accused the documentary of losing objectivity. Defenders argued it was simply showing the full truth, including the unexpected connections that formed during years of filming.

In 2022, HBO Max released a dramatized version starring Colin Firth as Michael and Toni Collette as Kathleen. The series took creative liberties but introduced the case to yet another generation.

The Peterson case has become a fixture in true crime culture. Podcasts dissect every detail. Reddit threads debate the evidence. YouTube videos analyze the 911 call frame by frame.

Everyone has a theory. No one can prove it.

The Legacy

The Michael Peterson case changed American forensic science.

The Duane Deaver scandal exposed systemic problems in how expert testimony was presented in criminal trials. Blood spatter analysis, once treated as near-infallible science, came under intense scrutiny.

Hundreds of cases in North Carolina were reviewed. Some convictions were overturned. New standards were implemented for forensic analysts, requiring better documentation and more rigorous qualification standards.

Defense attorneys across the country began challenging prosecution experts more aggressively. The Peterson case became a cautionary tale about trusting “expert” testimony without examining the science behind it.

The case also highlighted how sexual orientation could be weaponized in criminal trials. Michael’s bisexuality was irrelevant to whether he’d killed his wife, but prosecutors used it to paint him as deceptive and morally compromised. The LGBTQ advocacy community pointed to the trial as an example of lingering prejudice in the justice system.

And then there’s the owl theory—perhaps the case’s strangest legacy.

What started as a seemingly absurd defense has gained scientific legitimacy. Wildlife experts now take seriously the possibility that a barred owl could inflict injuries severe enough to kill a human. Warning signs have been posted in some parks about aggressive owl behavior during nesting season.

Whether or not an owl killed Kathleen Peterson, the theory forced legal and scientific communities to consider alternative explanations that seemed too bizarre to contemplate. Sometimes the truth is stranger than any story we’d invent.

The Impossibility of Certainty

Here’s what makes the Peterson case so enduringly fascinating: it resists easy answers.

This isn’t a case where new DNA evidence will suddenly reveal the truth. It’s not a mystery waiting for someone to discover the crucial piece of overlooked evidence. All the evidence has been examined, reexamined, fought over by experts on both sides.

The truth is that we’re left with competing narratives, each supported by some facts, contradicted by others.

Michael Peterson as murderer: Supported by motive, opportunity, suspicious circumstances, and the Elizabeth Ratliff connection. Contradicted by the lack of skull fracture, discredited blood spatter evidence, and the scientific plausibility of alternative explanations.

Michael Peterson as innocent victim of tragedy and injustice: Supported by faulty forensic analysis, the owl theory, and the lack of direct evidence of murder. Contradicted by the multiple suspicious elements that seem too numerous to all be coincidence.

And in the middle, the owl—a theory so strange it seems like fiction, yet scientifically plausible enough that experts can’t dismiss it.

The Peterson case forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth about justice: sometimes we can’t know what really happened. Evidence can be ambiguous. Experts can disagree. And even after trials, appeals, documentaries, and decades of analysis, certainty can remain elusive.

A Family Forever Broken

Whatever happened on that December night, one truth is undeniable: a family was destroyed.

Kathleen Peterson’s daughter lost her mother and then lost the stepfather she’d trusted when she came to believe he’d killed her mother.

Michael’s children were forced to choose between believing their father and believing the justice system. Some chose one path, some chose another, and those choices created fractures that will never fully heal.

Margaret and Martha Ratliff lost their biological mother when they were toddlers, were raised by a man who loved them, and then had to face questions about whether that man had killed their mother too. That’s a burden no one should carry.

Clayton and Todd Peterson watched their father go to prison for eight years, then live under house arrest for five more, all while maintaining his innocence. Even his release didn’t bring closure—just a legal compromise that left everyone unsatisfied.

Caitlin Atwater lives with the belief that her mother’s killer walked free. That’s a wound that doesn’t heal.

And Michael Peterson, now in his eighties, lives under a cloud of suspicion that will follow him to his grave. Whether innocent or guilty, he’s forever the man at the center of one of America’s most controversial cases.

What Kathleen Knew

In all the analysis, expert testimony, and legal maneuvering, it’s easy to lose sight of Kathleen herself.

She was forty-eight years old. A woman who’d broken barriers and built a successful career. A mother who loved her daughter fiercely. Someone who made people laugh at dinner parties and gave her time to arts organizations she believed in.

On December 9, 2001, Kathleen Peterson went to bed expecting to wake up and go to work on Monday. She had emails to answer. A conference call to prepare for. Normal concerns of normal life.

Instead, she died in her own home under circumstances so mysterious that more than two decades later, we still don’t know what happened to her.

If she fell, she died alone and frightened, perhaps confused about why she couldn’t stand, couldn’t stop bleeding.

If an owl attacked her, she died from a freak accident so bizarre that most people find it hard to believe.

If Michael killed her, she died at the hands of someone she loved and trusted, betrayed in the worst possible way.

We’ll never know which truth Kathleen would tell us if she could.

The Staircase Stands Empty

The house at 1810 Cedar Street is quiet now.

New owners have made it their own. They’ve repainted walls and replaced fixtures. The staircase where Kathleen died has been completely rebuilt—new wood, new railings, nothing left of the structure that investigators photographed that December morning.

Neighbors rarely mention the house’s history. It’s just another home in Durham’s Forest Hills neighborhood, valued for its size and location rather than its past.

But the case lives on in a way the physical location doesn’t.

It lives in true crime forums where people debate the evidence endlessly. In law school classrooms where professors use it to teach about forensic science and reasonable doubt. In documentary series that keep introducing new audiences to the mystery.

The Peterson case has become a Rorschach test. What people believe about it often says more about them than about the evidence.

Those who trust the justice system tend to believe the jury got it right the first time. Those who are skeptical of prosecutorial power see an innocent man railroaded by faulty science. True crime enthusiasts fascinated by bizarre possibilities are drawn to the owl theory.

Everyone finds in the case what they’re predisposed to see.

Twenty-Three Years Later

December 9, 2024 marked twenty-three years since Kathleen Peterson’s death.

There was no media coverage. No new revelations. The anniversary passed quietly, noted only by those whose lives were directly touched by that night.

Michael Peterson is old now. The charming novelist who once hosted elaborate parties is in his eighties, living quietly, his story told so many times it’s become rehearsed. Whether he’s a man wrongly convicted who lost sixteen years to a broken system, or a murderer who escaped justice through legal technicalities, only he knows for certain.

Caitlin Atwater is in her fifties. She’s built a life for herself, one that doesn’t include the man she once called Dad. She rarely speaks publicly about her mother’s death anymore, but those who know her say the loss and betrayal still define parts of who she is.

The Peterson sons, Clayton and Todd, remain loyal to their father. They’ve defended him consistently for over two decades. That kind of conviction—whether it’s born from truth or from a refusal to accept an unbearable alternative—is remarkable in its own right.

And somewhere in North Carolina’s woods, barred owls still nest in the trees, territorial and aggressive, occasionally attacking humans who get too close to their territory. Whether one of them killed Kathleen Peterson will likely remain forever unknown.

The Final Mystery

In the end, the Michael Peterson case is about the limits of certainty.

We want answers. We want to know what happened. We want justice to be clear and truth to be obvious.

But reality doesn’t always cooperate.

Sometimes evidence is ambiguous. Sometimes experts disagree. Sometimes the most bizarre explanation can’t be ruled out. And sometimes, despite trials and appeals and documentaries and decades of analysis, we’re left with questions instead of answers.

Two women died at the bottom of staircases. One man was present at both scenes. Everything else is interpretation, theory, belief.

Was it murder? Was it accident? Was it something in between that we don’t have a clear word for?

The North Carolina justice system said yes, then said maybe, then said “close enough” and moved on.

The family remains divided.

The evidence remains contradictory.

And Kathleen Peterson remains frozen in time, forty-eight years old forever, her death as mysterious now as it was that December morning when Michael Peterson called 911 and started a chain of events that would captivate America for over two decades.

The staircase at 1810 Cedar Street is empty now. Rebuilt. Repainted. Ordinary.

But the questions remain.

And perhaps that’s the most unsettling truth of all: sometimes there are no answers. Only the stories we choose to believe about what might have happened in the darkness when no one else was watching.