THE LAST KNOWN MOMENT

The autumn evening of October 3rd, 2011, started like any other Tuesday in Kansas City. The leaves were beginning to turn amber and gold, and a cool breeze drifted through the northeast neighborhoods where ordinary people were settling into their ordinary routines. But in a modest, light-green ranch-style home on North Lister Avenue, something was about to unfold that would shatter countless lives and divide an entire nation’s attention for years to come.

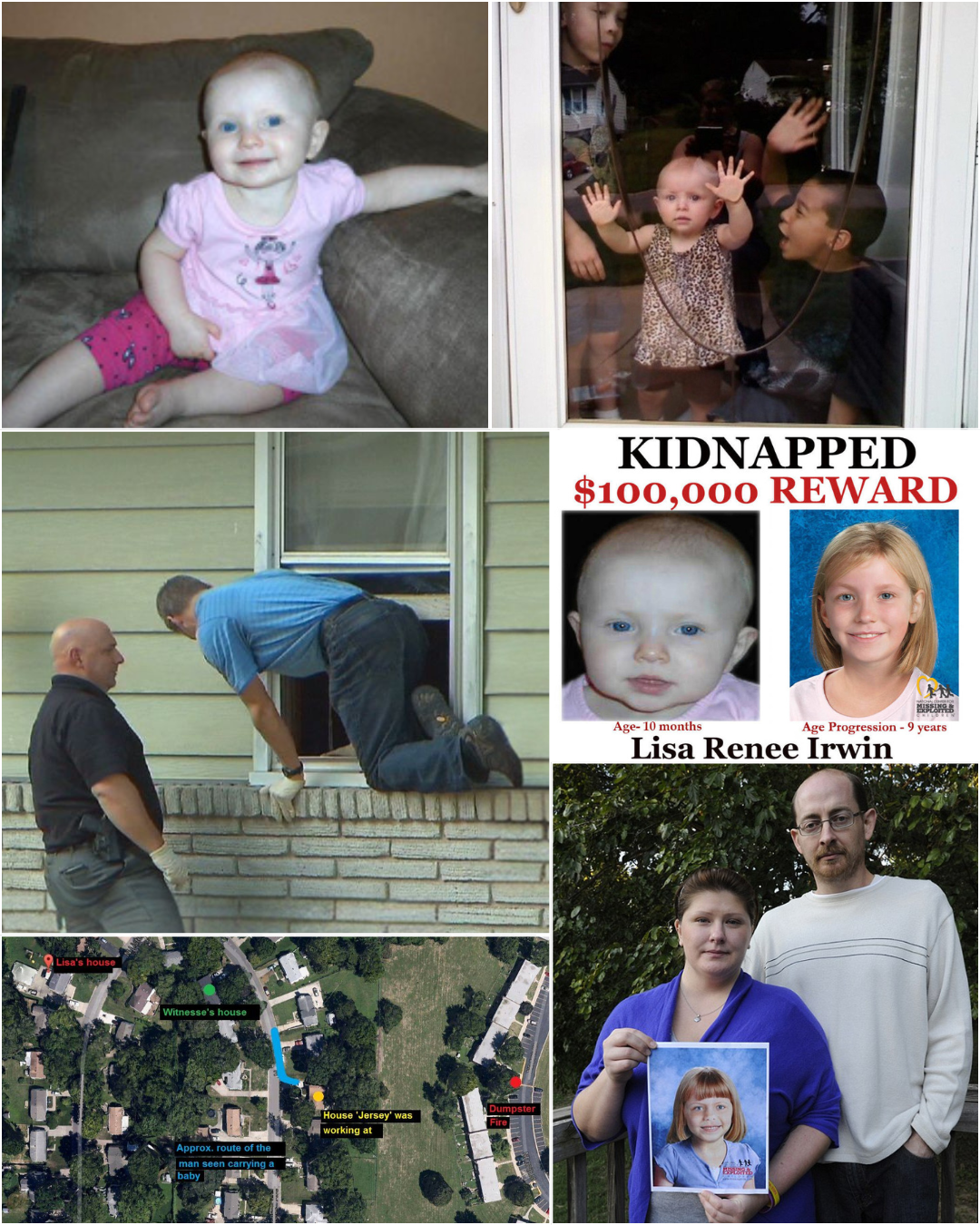

Deborah Bradley, a young mother, stood in the kitchen of her family home that afternoon with her infant daughter, Lisa Renee Irwin. Lisa was just ten months old—barely able to sit up on her own, her round baby face still bearing the soft features of someone who had experienced almost nothing of the world beyond her crib and the arms of her parents. She was the youngest of three children in the household, following her two older half-brothers, Blake and Jayden, ages five and eight. The home hummed with the quiet rhythm of a family going through the motions of an ordinary day.

Around 5 p.m., something unremarkable happened that would later become scrutinized under the harsh glare of national attention. Deborah and her brother ventured out to Festival Foods, a local supermarket just minutes from their home. They weren’t going on any special shopping expedition. What they purchased that evening could be found in the shopping carts of thousands of American families every single day: diapers for Lisa, baby wipes, and a box of wine. The surveillance footage from the store would later capture them on camera—a routine errand, nothing sinister, nothing that suggested anything unusual was about to occur.

By 5:30 p.m., Jeremy Irwin, Lisa’s father, was preparing to leave for work. Jeremy worked the night shift as an electrician, a job that required him to be away from home during the hours when most families were settling in for dinner and bedtime routines. He kissed his children goodbye, perhaps lingering a moment longer with little Lisa, as fathers often do. He had no way of knowing this would be one of the last times he would see his daughter in his own home.

As evening fell, Deborah moved through the familiar choreography of putting small children to bed. Around 6:40 p.m., she placed baby Lisa into her crib in the bedroom. The baby drifted off to sleep as infants do—peacefully, without worry, without knowledge of the darkness that was creeping toward her like a shadow across a wall. Deborah would later claim this was the last time she remembered seeing her daughter with absolute clarity. At that moment, Lisa was safe, warm, and asleep in her crib.

But as the night deepened, details become murky—shrouded in a fog of memory that would later become one of the most contested aspects of this entire case.

Around the same time that Lisa was being tucked into bed, a neighbor was settling down on Deborah’s porch with her. They cracked open that box of wine Deborah had purchased earlier that day. What began as a casual evening between neighbors evolved into something that would later define the entire investigation. Glass after glass was poured. Deborah drank. She would later admit she consumed between five and ten glasses of wine that night—enough to render someone significantly intoxicated, enough to cloud judgment, blur memories, and raise profound questions about supervision and awareness.

This admission would haunt Deborah for the rest of her life.

At some point during the evening, as the wine glasses accumulated on the porch table and darkness settled fully over Kansas City, Deborah was asked by the neighbor when she had last checked on her baby. According to Deborah’s initial account to police, she had checked on Lisa at 10:40 p.m. At that moment, she claimed, the baby was still there in her crib, undisturbed and asleep. Everything was normal. Everything was fine.

But even in this detail, questions would later emerge. Why was Deborah’s memory so precise about a 10:40 p.m. check-in when the rest of the evening was becoming increasingly hazy with wine? What did she actually see? What did she miss in her state of intoxication? These questions would linger like ghosts.

What happened between 10:40 p.m. and 4 a.m. would become the heart of the mystery—a gap of more than five hours where a baby vanished without a trace, a gap that no one could fully explain.

Around midnight, according to later investigations, something else caught the attention of neighbors and would-be investigators. A mysterious phone call was made from Deborah’s cell phone to another phone belonging to someone named Megan. The call lasted less than a minute. Deborah herself didn’t make the call—or so she would claim. According to later theories, someone else had access to her stolen cell phone. But who? And why would they be calling Megan at midnight? The answers would remain elusive, buried beneath layers of suspicion and incomplete evidence.

Between midnight and 12:30 a.m., something else occurred that would seize the imagination of investigators and amateur sleuths alike. Two separate witnesses—a couple driving through the neighborhood—reported seeing a man walking down the street in the darkness. The man was wearing a white t-shirt. And cradled in his arms was a small baby, wearing nothing but a diaper. The couple described watching this scene unfold in real time, struck by how unusual it was to see a man carrying an infant in the middle of the night, in the cold, dressed so scantily.

The image burned itself into their memory. A man. A baby. The middle of the night. No explanation. No context.

Around the same time, a dumpster fire erupted in the vicinity of nearby apartments—a fire that seemed to burn hot and fast, then disappeared just as quickly. Police would later wonder: was this a distraction? A cover-up? Or simply a coincidence in a city where crime and chaos were never far from the surface?

Then came 2:30 a.m. Another sighting. Another mysterious man in a white t-shirt, this time seen emerging from a wooded area near a gas station, captured on surveillance footage that would later be reviewed frame by frame by investigators searching for answers. The footage showed him moving with apparent urgency, moving away from the area where Lisa’s home was located. Was this the same man? Was he fleeing? Was he carrying anything? The video quality wasn’t clear enough to provide definitive answers, but it was clear enough to fuel endless speculation.

Around 4 a.m., there came a moment that would crystallize into the central trauma of this case—a moment that would replay in the minds of everyone who heard about it. Jeremy Irwin pulled into his driveway after his night shift, ready to come home to his family, ready to end another work day and collapse into bed. He had no idea his world was about to shatter.

As he approached his front door, something immediately struck him as profoundly wrong. The front door was not locked. It was unlocked—open to anyone or anything. Inside, the lights were blazing. Multiple lights throughout the house were switched on, flooding the interior with brightness. A window was open, and glass lay scattered on the floor. Someone—or something—had forced their way in.

Jeremy’s heart must have begun to race as he moved through the house, his mind racing through possibilities, his stomach beginning to tighten with a premonition of tragedy. He moved toward the bedroom where Lisa slept. He looked into the crib.

It was empty.

The crib was empty. The small form of his baby daughter was gone. The spot where she should have been lying, the indentation her tiny body should have left on the mattress, the presence he should have felt—all of it was absent. In that moment, Jeremy Irwin’s life changed forever. In that moment, he became the father of a missing child.

But Jeremy noticed something else, something that would add another layer of mystery to an already nightmarish situation. Cell phones were missing from the house. Multiple cell phones. Deborah had been frantically trying to explain this detail to police: “They took her and took all of our phones so we couldn’t call anybody.” Three cell phones, vanished along with Lisa.

Why would an intruder take cell phones? Was the goal to prevent the parents from immediately calling for help? Was it to eliminate evidence? Or was it something else entirely—something that pointed toward an explanation that was far more complicated and far more terrible than anyone wanted to consider?

At 4:07 a.m., the first call came through to the Kansas City 911 dispatch center. Jeremy’s voice came across the line, frantic and desperate, reporting that his ten-month-old daughter was missing. Within minutes, police would be at the scene. Within hours, the story would begin to leak to the media. Within days, it would become a national sensation, capturing headlines across America, generating countless theories, and dividing the nation into camps of believers—those who believed an intruder had taken Lisa, and those who believed someone inside the home bore responsibility for her disappearance.

But as dawn broke over Kansas City on October 4th, 2011, no one could have predicted how this case would metastasize into an American mystery that would still be unsolved fourteen years later, still generating documentaries, still captivating true crime audiences, still raising impossible questions about maternal responsibility, criminal investigation, and the fragility of a baby’s life.

THE INVESTIGATION UNFOLDS – SUSPICION, SECRETS, AND THE NATION DIVIDED

The sun rose on October 4th, 2011, but it would bring no clarity—only darkness of a different kind. Within hours of Lisa’s disappearance being reported, Kansas City police and FBI agents descended upon the modest house on North Lister Avenue like wasps to honey. The initial fear that gripped the neighborhood—the thought of a predator at large, an intruder who had slipped through a window in the dead of night and stolen an infant from her crib—began to morph into something far more complicated and sinister. Doubt crept in. Suspicion flourished. And before anyone could fully process what had happened, the investigation had begun to pivot inward, casting its searchlight not outward toward potential kidnappers, but inward toward the family itself—specifically, toward Deborah Bradley, the mother who had been alone with her baby while drinking wine on the night she vanished.

The first crack in the foundation came almost immediately. When police began reconstructing the timeline with Deborah, they noticed inconsistencies—little contradictions that, on their own, might have meant nothing, but woven together began to form a pattern that troubled investigators. Deborah’s memory of that evening, they discovered, was far more fragmented and unreliable than one might expect from a mother recounting the last moments she saw her child alive.

Initially, when police asked about her drinking, Deborah minimized it. She said she’d had just a few glasses of wine—maybe three or four. A social amount. Nothing concerning. Nothing that should interfere with her ability to supervise a baby. But as investigators pressed, as they spoke to her neighbors and friends who had been present that evening, the story began to unravel. The truthful narrative emerged, piece by piece, until it became clear that Deborah had consumed far more than she initially admitted. Between five and ten glasses. A significant amount of alcohol. Enough to genuinely impair judgment, memory, and the ability to reliably supervise an infant.

But here was the deeper problem: Deborah had also radically altered her account of when she last saw Lisa. She had initially told police that she had checked on her daughter at 10:40 p.m., finding her asleep and undisturbed. But when investigators checked her phone records, when they spoke to neighbors, when they began to piece together the actual timeline of that evening, the truth emerged that was far more damaging. The last time Deborah could definitively remember seeing Lisa was at 6:40 p.m.—hours before she claimed to have checked on her. A gap of sixteen hours. Sixteen hours during which Deborah had been consuming wine, during which her memory had become increasingly unreliable, during which anything could have happened to her infant daughter without her knowledge or intervention.

This discrepancy—this dramatic collision between Deborah’s stated recollection and the timeline investigators could verify—became a fissure in the case that would never quite be healed. How could a mother be so certain she had checked on her baby at 10:40 p.m. when no objective evidence supported that claim? How could her memory have been so precise about that specific moment while everything else about the evening was dissolving into haze and contradiction?

Police decided to administer a polygraph test to Deborah Bradley. The decision made tactical sense—if she was lying about her involvement, the polygraph might reveal deception. If she was truthful, the test would help exonerate her and allow investigators to focus their resources elsewhere. But what happened next would become one of the most contested and controversial aspects of this entire investigation.

Deborah agreed to take the test. She sat in the chair with the sensors attached to her body, her heart rate and breathing patterns being monitored, ready to answer questions about her daughter’s disappearance. According to police statements, she failed the test. The indicators suggested deception—that she was not being truthful when answering questions about what she knew about Lisa’s disappearance.

But Deborah vehemently rejected this conclusion. She insisted she had not failed. She claimed police had misrepresented the results to her. She maintained, with a conviction that would never waver throughout the years to follow, that she had nothing to do with her daughter’s disappearance. Yes, she had been drinking. Yes, her memory was unreliable. Yes, there were gaps in her recollection that she couldn’t explain. But none of that meant she was responsible for Lisa vanishing.

“From the start when they questioned me, once I couldn’t fill in the gaps, it turned into ‘You did it, you did it,’” Deborah would later tell Good Morning America, her voice trembling with the weight of accusation and the burden of being unable to prove a negative. “They took a picture down from the table and said, ‘Look at your baby! And do what’s right for her!’ I kept saying I don’t know.”

The polygraph result became gasoline on the fire of public suspicion. It was leaked to media outlets. News anchors began reporting that Deborah had failed a lie detector test. The implication hung heavy in the air: if she had failed, if she was being deceptive, perhaps she knew more about her daughter’s disappearance than she was admitting. Perhaps—the thought was too terrible to voice openly, but it whispered through every news segment—perhaps Deborah Bradley had done something to her own child.

But there was another side to this story, one that forensic experts and defense attorneys would point to. The reliability and admissibility of polygraph tests have been the subject of fierce debate in law enforcement and legal circles for decades. Polygraphs don’t actually detect lies—they detect physiological responses to stress, anxiety, and heightened emotional states. An innocent person who is terrified, confused, or traumatized can display the same physiological markers as a guilty person actively engaged in deception. And Deborah Bradley, on the night she took that test, had been subjected to hours of aggressive interrogation, had been accused of harming her own child, and was sitting in a police station while her infant daughter remained missing. Her stress levels would have been catastrophically elevated. Her anxiety would have been through the roof. Of course the polygraph might have registered “deception”—she was in a state of psychological crisis.

The family’s attorney, Cyndy Short, seized on this point. She appeared on national news programs defending Deborah, questioning whether police had handled the polygraph test properly and whether the results should be given any credence whatsoever.

But the damage was already done. In the court of public opinion, polygraph results are powerful symbols. Even though they’re inadmissible in most courtrooms, even though they’re scientifically questionable, they carry weight in the minds of ordinary people watching news reports. The narrative began to take shape: the mother had failed a polygraph. The mother had been drinking. The mother’s story didn’t add up. Therefore, the mother must be guilty.

Jeremy Irwin, for his part, offered to take a polygraph test as well. But police declined the offer. They said it wasn’t necessary. This detail would later become another point of contention—why would police refuse a polygraph from the father? Some speculated that investigators had already decided where their suspicions lay and had no interest in information that might complicate that narrative.

Then came the moment that would grip the nation’s attention with particular intensity: the arrival of the cadaver dogs.

On October 17th, 2011—thirteen days after Lisa’s disappearance—specialized search dogs trained to detect the scent of human decomposition were brought into the home. These were not ordinary police dogs. These were FBI cadaver dogs, animals that had been trained through rigorous protocols to identify the specific biochemical markers that indicate the presence of decaying human remains. They could detect scents that had lingered for years, scents that had seeped into carpet fibers and floorboards, scents that human noses could never perceive.

The search was conducted with the parents’ permission and cooperation. The dogs moved through the rooms of the house, their handlers watching carefully for any behavioral indication that the dogs had detected something significant. And then it happened—one of the dogs reacted. It “alerted” to a spot in the bedroom. Specifically, the dog indicated a positive “hit” for the scent of a deceased human on the floor of the master bedroom, near Deborah’s bed.

The implications hit like a physical blow. If the dog was correct, if it was reliable, if the scent truly indicated the presence of human decomposition—then Lisa had died in that bedroom, near where her mother slept. Not in her crib in the baby’s room. Not at the hands of an intruder in the darkness. But here, in this bedroom, close to Deborah. The theory of a kidnapping began to fracture. A new narrative began to emerge: What if Lisa hadn’t been taken? What if something had happened to her in the home? What if her mother, intoxicated and impaired, had been unable to properly supervise her? What if—and the thought was almost unbearable—what if Deborah was somehow responsible?

But the family’s attorneys fired back with their own counter-argument. They pointed out that the house was 63 years old. Cadaver dogs, they explained, can detect decomposition that has been present in a structure for decades. An older home could have absorbed the scents of previous deaths, previous traumas, previous decomposition events that had nothing whatsoever to do with Lisa Irwin. The positive alert, they argued, was essentially meaningless. It proved nothing except that an old house contained old scents.

Moreover, they questioned the very premise: if Lisa had died in that bedroom just hours before police arrived, would decomposition have progressed far enough to be detectable by dogs trained to identify such scents? Decomposition is a gradual process. It takes time. The scent of death is not instantaneous. A dog might alert to weeks-old remains, but hours? The science seemed questionable. The family’s attorney, attorney Joe Tacopina, stated flatly that even if Lisa had died, decomposition could not have progressed rapidly enough to be detectable within such a short timeframe.

But the damage had been done. The cadaver dog alert became another piece of evidence in the court of public opinion—another thread in the web of suspicion surrounding Deborah Bradley.

Meanwhile, other evidence was emerging that complicated the narrative further. There were the witness sightings—multiple credible witnesses who reported seeing a man carrying a baby in the early morning hours of October 4th, within minutes of Lisa’s disappearance. At 12:50 a.m., a husband and wife reported seeing a man walking down the street in a white t-shirt carrying a baby wearing only a diaper. It was approximately 45 degrees outside—cold enough that a baby would need more clothing. The couple found the sight unusual enough to mention it. They were only three houses away from the Irwin family home.

Then there was the surveillance video from a BP gas station less than two miles away. At 2:15 a.m., a camera captured footage of a man walking along the road—a man whom the gas station manager said was highly unusual to see in that area at that time of night. Investigators and the public pored over the grainy footage, trying to determine if this man could be the same person the couple had seen carrying a baby hours earlier. Could he be a fleeing abductor? Could he be connected to Lisa’s disappearance?

There was also the matter of the dumpster fire. In the early morning hours of October 4th, a dumpster fire erupted in a nearby apartment complex. The fire was strange—it burned hot and fast, then was extinguished. When police investigated, they discovered baby clothes in the dumpster. They weren’t the specific clothes Lisa had been wearing, but they were an infant’s garments. Were they Lisa’s? Could they be? Or were they coincidental—evidence of some other family’s laundry day gone wrong?

The questions multiplied. The possibilities fractured into endless variations. Was there truly an intruder? Had someone really climbed through that window and taken Lisa? Police conducted a crime scene reenactment to test this theory. They brought in officers who attempted to climb through the window that Jeremy said had been forced open. But when they examined the window closely, they found problems with the intruder theory. The window was high off the ground. The windowsill had dirt on it—dirt that didn’t appear to have been disturbed. Would a real intruder have climbed through without leaving any trace of dirt on their clothing? Would they have left the windowsill undisturbed? The reenactment raised more questions than it answered.

As the investigation deepened, as the weeks turned into months, the case became increasingly polarized in the public mind. Some believed firmly that an intruder had taken Lisa, that the witness sightings were crucial evidence, that law enforcement was focusing on the wrong person and allowing the real culprit to escape. These believers pointed to the multiple sightings of a man carrying a baby, to the surveillance footage, to the witness accounts. An intruder had taken Lisa, they insisted. The police needed to search for him.

But others—growing in number as weeks went by—became convinced that the truth was far darker and far more internal. They believed that Deborah knew something. They believed that the polygraph failure meant something. They believed that the cadaver dog alert was significant. They believed that a mother, impaired by alcohol, had lost track of her infant daughter, and that something terrible had happened in that home while she was unconscious or too intoxicated to notice. Perhaps Lisa had suffocated. Perhaps she had choked. Perhaps she had fallen from her crib. And perhaps, these people believed, Deborah had panicked, had called someone to help her, had disposed of evidence to protect herself, and had invented the story of an intruder to avoid responsibility.

The nation became divided into these two camps, separated by the fault lines of evidence that could be interpreted multiple ways, by witness accounts that complicated rather than clarified, by forensic evidence that was subject to competing interpretations.

Deborah and Jeremy, increasingly frustrated by the direction of the investigation, began to pull back their cooperation. They stopped speaking extensively with police. They lawyered up. They ceased allowing investigators free access to their home. A search warrant was eventually obtained to conduct a more thorough investigation, but by then, the critical early days had passed. Evidence that might have been preserved had been lost or compromised.

As weeks became months, as months became years, the case remained unsolved. There were no charges. There was no arrest. There was no closure. Lisa Irwin simply vanished, leaving behind only questions, suspicions, theories, and a nation divided about what had really happened in that house on October 4th, 2011.

The investigation had illuminated nothing so much as it had cast shadows everywhere.

THE UNANSWERED QUESTION – THIRTEEN YEARS OF HEARTBREAK, HOPE, AND PERSISTENT MYSTERY

Fourteen years have passed since that October morning when Jeremy Irwin came home to find his daughter’s crib empty. Fourteen years of seasons changing, of news cycles moving on to fresher tragedies, of the world forgetting about a baby girl who never got to grow up, never got to speak her own name aloud, never got to tell her own story. Yet for Deborah Bradley and Jeremy Irwin, those fourteen years might as well have been fourteen centuries—an endless stretch of time defined entirely by absence, by the haunting permanence of a question that has never been answered: Where is Lisa?

If Lisa Irwin were alive today, she would be fourteen years old. She would be a teenager, navigating the complicated terrain of adolescence, developing her own personality, her own opinions, her own dreams about the future. She would have a voice. She would have agency. She would be more than just a mystery. But instead, she exists only as a frozen moment in time—forever ten months old, forever captured in those final photographs taken before she vanished, forever suspended in the liminal space between the known and the unknowable.

The theories about what happened to Lisa have multiplied and evolved over the years like branches on an ever-growing tree. Some remain rooted in the possibility of an abduction. In recent years, private investigators hired by the family have focused attention on John “Jersey” Tanko, a local handyman and known transient who lived in a halfway house near the Irwin residence. Tanko matched the general description provided by some witnesses—a man of similar build and appearance to the figure seen carrying a baby in the early morning hours of October 4th. But despite this resemblance, despite the circumstantial connections, Tanko’s alibi held up under investigation. He was eventually ruled out as a suspect, his possible involvement relegated to the realm of speculation and “what if.”

Then there was the mysterious phone call. One of the three missing cell phones—Deborah’s phone—made a 50-second call to a woman named Megan Wright at 12:07 a.m. on the night Lisa disappeared. Deborah insists she didn’t make the call. Jeremy insists neither of them made it. So who did? And why? Private investigator Bill Stanton, hired by Lisa’s parents, told Good Morning America that this detail might be the key to the entire case. “This whole case hinges on who made that call and why,” Stanton stated flatly. “We firmly believe that the person who had that cell phone also had Lisa.”

But the investigation into that call led nowhere conclusive. Megan Wright denied being the one who answered. She claimed she wasn’t even sure if anyone had called her that night. The mystery of the call remained unsolved, another thread that could not be fully traced back to its source.

Other theories have centered on accidental death within the home. Some believe that Lisa may have suffocated in her sleep, or choked on something, or fallen from her crib while her mother was too intoxicated to notice or respond. These believers point to the cadaver dog alert as evidence of decomposition in the home. They suggest that in a panic, someone—perhaps Deborah, perhaps Jeremy—called someone to help dispose of the body to avoid charges of negligent supervision or worse. This theory explains the missing phones (to prevent calling 911), the disposed clothing found in dumpsters, the contradictions in the timeline.

But this narrative, despite its internal logic, has always lacked a crucial piece of evidence: an actual body. Where is Lisa? Where would she have been disposed of? Despite extensive searches—of landfills, of wooded areas, of abandoned buildings—no remains of Lisa Irwin have ever been found. The police have searched everywhere they’ve been permitted to search and many places they had to fight to access. Yet nothing. No bone. No burial site. No grave.

This absence of physical evidence has created a prosecution problem. Without a body, without forensic evidence definitively proving foul play, without a confession, the police have never had grounds to bring charges against anyone. The suspicion directed at Deborah remains exactly that—suspicion. The failed polygraph means nothing in court. The cadaver dog alert means nothing in court. The inconsistencies in her story, while troubling, are not enough. American law requires more than suspicion. It requires proof. And in the case of Lisa Irwin, that proof has never materialized.

Deborah and Jeremy have maintained their innocence consistently throughout the years. They have continued to speak to the media, to appear on national television, to plead for information about their daughter. On good days, Deborah speaks about Lisa as if her daughter is still alive somewhere, as if she’s simply waiting to be found. “I feel she’s alive. She’s out there and eventually she’s gonna come home,” she told reporters in 2021, a decade after the disappearance. It’s a hope that requires enormous emotional strength to sustain—the hope that your child is alive but has been taken from you, that she’s growing up somewhere without you, that she might not even know you exist.

The family has kept Lisa’s bedroom exactly as it was on the night she disappeared. It has become a kind of shrine—a room frozen in time, waiting for its occupant to return. Wrapped gifts line the shelves and furniture, marking every birthday, every Christmas, every special occasion Lisa has missed. When she turned six, her parents bought her a necklace with a topaz birthstone. At Halloween, Deborah purchased an Elsa costume from Frozen, even though there was no one to wear it, no little girl to delight in the Disney magic. These gestures might seem like denial to some observers, but to Deborah and Jeremy, they represent an unshakeable conviction that Lisa will come home, that these gifts will not be wasted, that someday they will have their daughter back.

The parents have also submitted their DNA to genetic databases, along with Deborah’s brother, in the hope that if Lisa is alive and grows up to submit her own DNA, or if her remains are ever discovered, the databases could provide a definitive connection. They have engaged private investigators who continue to pursue leads, no matter how tenuous. They have appeared on true crime documentaries, on news programs, on anything that might keep Lisa’s face in the public consciousness. They understand that forgotten cases receive no fresh leads, that attention is oxygen for cold cases. If Lisa is ever to be found, it will require someone—somewhere—to remember her, to see something, to come forward.

In August 2025, journalist Megyn Kelly, who had initially covered the case more than a decade earlier at Fox News, returned to investigate it again for a special program. The case has not been solved. No new arrests have been made. But the investigation continues in the way that investigations of the missing must continue—with periodic reviews, with new leads chased down, with the eternal question: What happened?

The broader impact of Lisa’s disappearance extended far beyond her family. The case became a lightning rod for national conversations about parental responsibility, about the dangers of intoxication while supervising children, about the reliability of forensic evidence, about police investigation tactics. It highlighted the tension between the protection of parental rights and the protection of children. It demonstrated how a single family tragedy could divide an entire nation into competing camps of belief and interpretation.

For Deborah Bradley specifically, the case has cast a long shadow. She has been publicly accused—on television, in newspapers, on the internet—of harming her own child. She has been called a suspect, has been branded guilty in the court of public opinion, despite never being charged with any crime. The weight of that suspicion has followed her for fourteen years, shaping her public persona, defining how she is perceived and understood.

Jeremy Irwin has similarly been shaped by the tragedy. The father who came home to find his daughter gone, who has spent fourteen years searching for her, has aged in ways that the mere passage of time cannot fully explain. There is a particular exhaustion that comes from unresolved loss, from the knowledge that your child is out there—somewhere—and you don’t know if she’s safe, if she’s alive, if she remembers you.

The two older brothers, Blake and Jayden, have grown up in the shadow of Lisa’s disappearance. What was a normal childhood before October 4th, 2011, became something fundamentally altered afterward. Their sister was taken—or was lost, depending on which theory one believes—and the entire family was plunged into a vortex of media attention, police investigation, and public scrutiny. They have had to develop their lives around this central tragedy, have had to answer questions about Lisa for most of their conscious years.

The case has also raised important questions about witness reliability and memory. The man seen carrying a baby on the night of Lisa’s disappearance—was he real? Or was he a phantom created by the power of suggestion, by the expectations created by the investigation itself? Memory is not a recording device. It is a reconstruction, malleable and influenced by context, emotion, and suggestion. The witnesses who claimed to have seen this man may have genuinely believed they saw him. But did they really? Or did they see something ambiguous and fill in the blanks with the fear and expectation generated by missing baby alert?

The investigation has also illustrated the limitations of forensic evidence. Cadaver dogs are useful tools, but they are not infallible. They can detect scents that have been present for years. They can false-alert to objects that resemble decomposition but are not. They can be influenced by their handlers’ expectations. Polygraph tests can reveal deception, but they can also be inconclusive or misleading. DNA evidence can solve cases, but only if there is DNA to test. In the absence of a body, in the absence of clear forensic markers, these tools become less powerful—they raise questions rather than answering them.

Perhaps the most tragic aspect of the Lisa Irwin case is its fundamental unresolvability. Unlike cases that are eventually solved—where an arrest is made, a trial occurs, justice is served or at least the truth is revealed—Lisa’s case may never be resolved. She may never be found. The mystery may persist for decades more, passing into the category of unsolved mysteries that haunt the American consciousness, that are revisited periodically by true crime enthusiasts and journalists seeking answers that may never come.

If Lisa was abducted, she could be anywhere in the world by now. If she’s alive, she could be living under an assumed name, completely unaware of her true identity. She might have memories of being taken, or she might have been too young to remember anything. She might one day see an age-progression photo or hear a news story and experience the shock of recognition. Or she might live her entire life unaware that she was once someone’s missing child, that she was the subject of national attention, that her parents never stopped looking for her.

If Lisa died that night—whether through accident or something darker—then she has been denied a life that she never got to live. She has been denied the chance to grow, to learn, to love, to experience the world. She exists only as a moment in time, captured in photographs, frozen at ten months old. For everyone who loved her, for everyone who has followed her case, she will always be that ten-month-old baby. She will never age beyond that moment. She will never have the chance to correct the record, to tell her own story, to have her voice heard.

The case of Lisa Irwin represents one of the fundamental failures of American law enforcement and the American justice system: the inability to solve certain cases, to find certain missing people, to provide families with the closure and answers they desperately need. It represents the limits of forensic science, the fallibility of witnesses, the complications that arise when circumstantial evidence can be interpreted multiple ways. It represents the tragedy of a child who vanished, leaving behind only questions and heartbreak.

As Lisa’s parents continue to age, as they move further away from that terrible October night in 2011, the question of what happened to their daughter becomes more urgent and more unlikely to be answered. Eventually, the people who know what really happened will themselves become old, and then they will die. The knowledge of what occurred—whether accident, whether murder, whether abduction—may very well die with them. Lisa Irwin may become one of America’s permanent mysteries, a case that is periodically revisited but never resolved, a tragedy that never reaches closure.

For fourteen years, Deborah and Jeremy have maintained hope. For fourteen years, they have kept Lisa’s room ready, bought presents for birthdays she doesn’t experience, prayed for her safe return. For fourteen years, they have carried the weight of suspicion, the scrutiny of public judgment, the exhaustion of uncertainty. And they will continue to carry this weight for as long as they live, because there is no alternative. To stop hoping would be to surrender to the possibility that they will never see their daughter again. And that is a surrender that parents cannot make.

Lisa Irwin remains missing. She remains a question without an answer, a mystery without resolution, a tragedy that divided America and never got the chance to unite it through the revelation of truth. She is the embodiment of unfinished business, of loss that cannot be completed, of grief that cannot be fully processed because the fundamental details of the case remain unknowable. Fourteen years later, the night that Lisa Irwin vanished is still dark. And in that darkness, somewhere, the answers remain hidden.