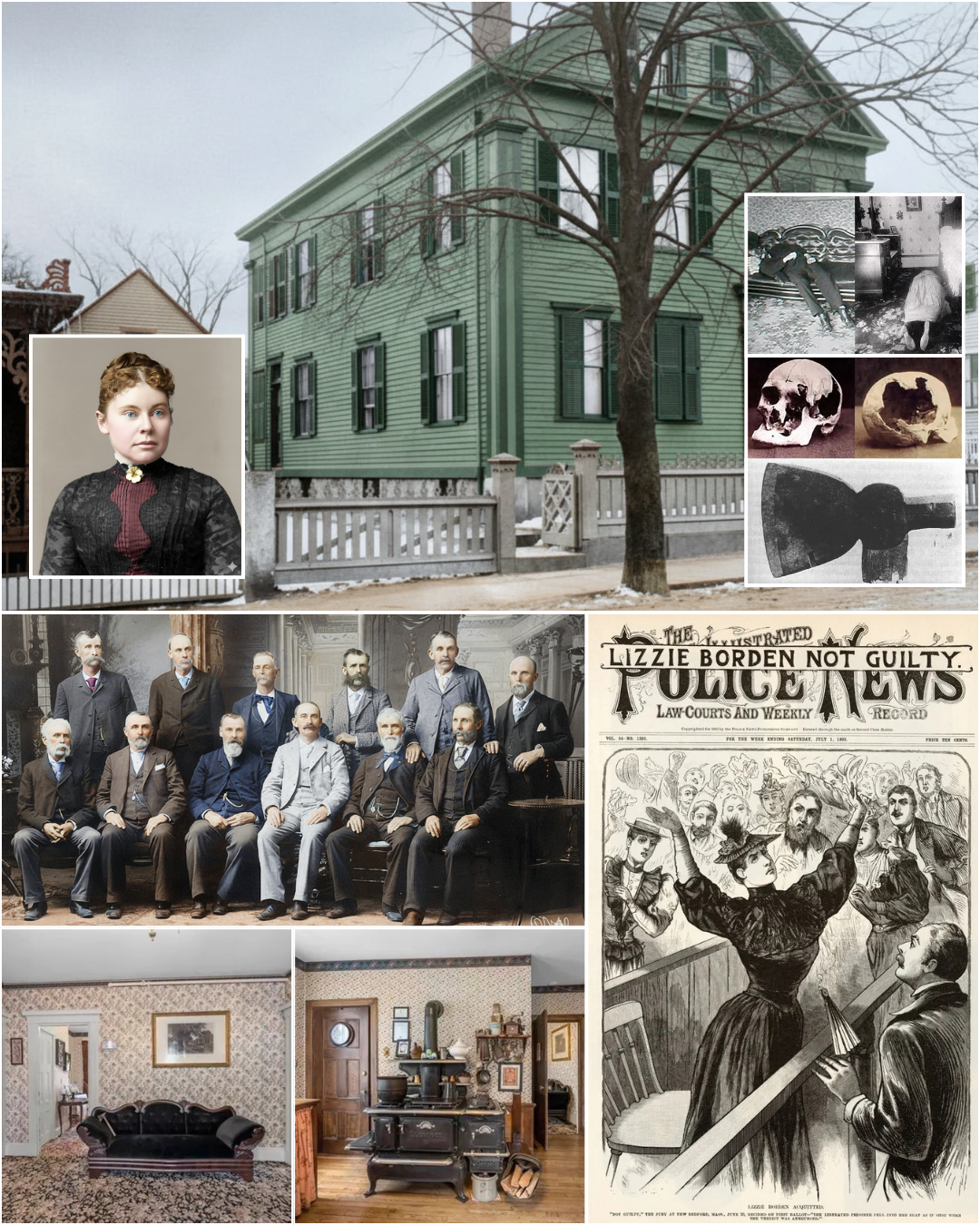

The heat had been unbearable that morning. August 4, 1892, in Fall River, Massachusetts, dawned with the kind of oppressive humidity that made breathing feel like work. Inside the modest two-story house at 92 Second Street, the Borden family went about their morning routines, unaware that by noon, two of them would be dead and one would become the most infamous woman in American history.

Andrew Borden, a wealthy businessman worth nearly half a million dollars—an enormous fortune in 1892—left for his daily rounds downtown that morning. His wife Abby stayed behind to tidy the guest room upstairs. Their daughter Lizzie, thirty-two years old and unmarried, remained somewhere in the house. The Irish maid, Bridget Sullivan, washed windows in the stifling heat.

By eleven o’clock, everything had changed.

The Discovery

Lizzie’s voice cut through the summer air with urgency. She called for Bridget to come quickly—her father had been hurt. When the maid rushed inside, she found Andrew Borden lying on the sofa in the sitting room. But “hurt” was a grotesque understatement.

Andrew Borden’s face had been destroyed. Someone had struck him repeatedly with a sharp instrument—later determined to be a hatchet or axe—while he lay sleeping. One blow had severed his eyeball completely. Another had split his nose in two. The blood was still fresh, still warm. Medical examiners would later determine he had been dead for less than two hours when his body was discovered.

Bridget ran for help while Lizzie stood in the house, seemingly in shock. Neighbors arrived within minutes. A doctor came to examine the body. And then someone thought to ask about Abby, Andrew’s second wife and Lizzie’s stepmother.

Where was Mrs. Borden?

Lizzie said she thought she had heard her stepmother come in earlier—someone had left a note asking her to visit a sick friend. But when the neighbors searched the house, they found Abby upstairs in the guest bedroom, lying face-down on the floor between the bed and the wall.

She had been struck nineteen times. The back of her head had been turned into pulp. Blood spattered the walls and floor. And unlike Andrew, Abby had been dead for over an hour—perhaps as long as ninety minutes—before her body was found. She had died first, while Andrew was still out on his morning errands.

Someone had killed them both, in their own home, in broad daylight, on a busy street in the middle of a Thursday morning.

The Only One Home

The investigation began immediately. Police questioned everyone in the household. Bridget Sullivan had been outside washing windows for most of the morning, in full view of neighbors. She had a solid alibi.

Lizzie’s older sister Emma had been out of town for two weeks, visiting friends in Fairhaven, fifteen miles away. She could not have been present.

John Morse, Andrew’s brother-in-law who had been visiting, had left the house early that morning and spent hours across town. Multiple people confirmed seeing him nowhere near Second Street.

That left Lizzie.

She had been in the house all morning. She claimed she had gone out to the barn behind the house to look for fishing sinkers, spending perhaps twenty minutes in the loft. But when police checked the barn, they found the loft floor covered in undisturbed dust. No footprints. No sign anyone had been up there recently.

Her story kept changing. First she said she was in the kitchen. Then the yard. Then the barn. She told one neighbor she had been upstairs when she heard her father come home. She told another she had been downstairs the entire time. Her accounts of the morning contradicted each other at nearly every turn.

Even more troubling, Lizzie showed almost no emotion. While neighbors wept and recoiled in horror at the brutal scene, Lizzie remained calm, her face expressionless. Newspapers would later describe her demeanor as “stolid”. Some saw it as shock. Others saw something far more sinister.

The Evidence Mounts

As investigators dug deeper, unsettling details emerged. The day before the murders, Lizzie had tried to purchase prussic acid—a deadly poison also known as hydrogen cyanide—from a local drugstore. She claimed she needed it to clean a sealskin cloak. The druggist refused to sell it to her.

Relations between Lizzie and her stepmother had been icy for years. Lizzie refused to call Abby “Mother,” instead referring to her as “Mrs. Borden”. When Andrew gave Abby’s half-sister a house as a gift, Lizzie and Emma had been furious. Andrew tried to smooth things over by giving his daughters property of their own, but the resentment lingered.

Money was another source of tension. Andrew Borden was notoriously frugal despite his wealth. The house had no indoor plumbing, no gas lighting, no modern conveniences. He kept tight control over every penny. If Andrew died, Lizzie and Emma stood to inherit a substantial fortune.

Then there was the matter of the dress. Three days after the murders, Emma saw Lizzie burning a dress in the kitchen stove. When questioned about it later, Lizzie explained the dress had been stained with paint and was old and faded. Emma confirmed this at trial. But the timing looked damning.

Most damaging of all, no weapon was ever found. Police searched the house, the yard, the neighborhood. They found a hatchet with a broken handle in the basement, but it showed no signs of blood. They found no bloodstained clothing. No murder weapon. Nothing that directly connected Lizzie to the crimes.

And yet she had been the only person home.

The Arrest

On August 11, 1892, one week after the murders, police arrested Lizzie Andrew Borden and charged her with killing her father and stepmother. The case made national headlines. A respectable woman from a prominent family, a Sunday School teacher known for her charity work, now sat in jail accused of one of the most brutal murders Massachusetts had ever seen.

The preliminary hearing drew enormous crowds. People lined up for hours hoping to catch a glimpse of the accused murderess. Her defense attorney gave an impassioned closing argument. Supporters in the courtroom burst into applause. But the judge ruled there was probable cause to believe Lizzie had committed the murders. She would remain in jail until trial.

For the next ten months, Lizzie Borden sat in a cell, waiting. Outside, public opinion split sharply. Some believed no respectable Christian woman could commit such savage acts. Others pointed to the evidence and asked: if not her, then who ?

The Trial Begins

When Lizzie’s trial finally opened on June 5, 1893, in New Bedford, Massachusetts, the circus atmosphere intensified. Reporters packed the courtroom. Artists sketched scenes for newspapers across the country. The case had become a national obsession.

The prosecution laid out its circumstantial case. They emphasized that Lizzie had been the only person in the house. They highlighted her inconsistent statements. They noted her attempt to buy poison the day before. They pointed to the burned dress. They argued she had motive—a difficult relationship with her stepmother and a desire for her father’s money.

But they had no direct evidence. No eyewitnesses. No murder weapon. Not a single drop of blood connecting Lizzie to the crimes.

The defense pounced on these weaknesses. Attorney George Robinson, a former governor of Massachusetts, argued that the prosecution had failed to prove their case beyond a reasonable doubt. Where was the weapon ? Where were the bloodstained clothes ? How could someone commit such brutal murders and leave absolutely no physical trace ?

One of the most dramatic moments came when prosecutors introduced the victims’ skulls as evidence. The heads had been removed during autopsy and the bones cleaned. On June 5, lawyers placed the skulls on a table in front of the jury. When Lizzie saw them, she fainted.

The prosecution tried to use her inquest testimony, which had been full of contradictions. But the judges ruled it inadmissible. At the time of the inquest, Lizzie had effectively been a prisoner charged with murder, questioned without her attorney present. Her statements could not be used against her.

This ruling dealt a severe blow to the prosecution’s case.

The Defense Strategy

Robinson and his team built their defense around Lizzie’s character and social standing. They emphasized she was a church member, a Sunday School teacher, a woman active in charitable works. They brought forward character witnesses who testified to her good reputation.

They also attacked the prosecution’s reliance on circumstantial evidence. Robinson reminded the jury that suspicion and probability were not the same as proof. The state had to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Anything less required an acquittal.

When Emma Borden testified about the dress Lizzie had burned, she confirmed her sister’s explanation. The dress had been old, faded, and paint-stained. Burning it had been perfectly reasonable.

The defense also noted the absence of blood. The murders had been extraordinarily violent and bloody. The killer would have been covered in blood spatter. Yet when neighbors and police arrived minutes after the discovery of Andrew’s body, Lizzie’s clothing was clean. Not a spot of blood anywhere.

How could she have committed these murders and cleaned herself so thoroughly in such a short time ?

The Prosecution’s Final Argument

Prosecutor William Moody knew his case was weak. In his closing argument, he made a calculated decision. He appealed not to evidence, but to stereotypes.

Women, he told the all-male jury, were different from men. They might lack physical strength, but they made up for it with cunning and dispatch. Their loves were stronger than men’s loves, he said—but their hates were more undying, more persistent.

It was a brazen attempt to convince the jury that Lizzie’s gender made her capable of this kind of calculated violence. Where men might kill in passion, women killed with cold planning. The prosecution wanted the jury to convict based not on evidence, but on prejudice.

The Judge’s Instructions

Before the jury began deliberations, Judge Justin Dewey delivered instructions that would prove decisive. He reminded jurors that the prosecution’s case rested entirely on circumstantial evidence. He noted that Lizzie’s inconsistent statements after the murders could be explained by shock and trauma.

Most importantly, he emphasized the standard of proof. If the evidence raised only suspicion, or even strong probability of guilt, that was not enough. The jury had a duty to acquit unless they were convinced beyond a reasonable doubt.

Judge Dewey’s instructions clearly favored the defense. Some historians have noted that Dewey had been appointed to the bench by George Robinson—Lizzie’s lead attorney—when Robinson had served as governor.

The Verdict

On June 20, 1893, the jury retired to deliberate. They had heard two weeks of testimony. They had seen the gruesome evidence. They had listened to passionate arguments from both sides.

After just one hour and thirty minutes, they returned.

The foreman stood when asked for the verdict.

“Not guilty,” he said simply.

Lizzie let out a cry. She collapsed into her chair, buried her face in her hands, and cried out again in joy. Her sister Emma rushed to embrace her. Lawyers and spectators crowded around to offer congratulations.

When she finally composed herself, Lizzie told reporters waiting outside: “I am the happiest woman in the world”.

She was free. The law had spoken. Lizzie Andrew Borden had been found not guilty of murdering her father and stepmother.

But the story was far from over.

Life After Acquittal

Lizzie did not leave Fall River. Despite being acquitted, despite the jury’s declaration of innocence, she remained in the town where everyone knew her name and believed they knew what she had done.

She and Emma used their inheritance to purchase a large house on “The Hill,” the fashionable part of Fall River. Lizzie renamed it “Maplecroft”. She finally had the modern home her father had always denied her—indoor plumbing, electricity, all the conveniences of turn-of-the-century life.

But Fall River society turned its back on her. Former friends stopped calling. Church members avoided her. She was never invited to social gatherings. Despite the jury’s verdict, the people of Fall River had reached their own conclusion.

Lizzie lived at Maplecroft for thirty-four years. She attended theater performances in Boston and Providence. She made a few friends. But she never escaped the shadow of August 4, 1892.

Emma eventually left, moving out after a quarrel in 1905. The sisters never reconciled. When Lizzie died of pneumonia on June 1, 1927, at age sixty-six, she died essentially alone. Emma died just days later.

Neither sister ever married. Neither ever spoke publicly about the murders. Whatever Lizzie knew—whether she was truly innocent or carried a terrible secret—she took it to her grave.

The Lingering Questions

The jury said not guilty. The law declared her innocent. But more than 130 years later, people still ask: did Lizzie Borden really get away with murder ?

The circumstantial evidence was compelling. She was the only person in the house. Her stories contradicted each other. She had tried to buy poison the day before. She burned a dress afterward. She had motive. She inherited a fortune.

But circumstantial evidence is not proof. The prosecution never found the murder weapon. They never explained how Lizzie could have committed such bloody murders without getting a single drop of blood on herself. They never provided a shred of physical evidence connecting her to the crimes.

The defense argued—and the jury agreed—that suspicion and probability are not the same as guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. In American law, it is better to let a guilty person go free than to convict an innocent one.

Lizzie Borden’s acquittal represented a triumph of that principle. The jury refused to convict based on gender stereotypes and circumstantial evidence alone. They followed the law, even when public opinion screamed for a different result.

And yet the question remains: if Lizzie didn’t do it, who did ?

Alternative Theories

Over the decades, investigators, historians, and amateur sleuths have proposed numerous theories about who really killed Andrew and Abby Borden. If Lizzie was innocent, as the jury declared, then someone else committed these brutal murders in broad daylight on a busy street.

Some pointed to Bridget Sullivan, the Irish maid. She had been in the house that morning. She had access to all areas. Perhaps tensions with the Bordens had boiled over into violence. But Bridget had been washing windows outside, visible to neighbors, during the critical time period. Multiple witnesses confirmed her whereabouts. She had no apparent motive. And like Lizzie, she showed no signs of blood on her clothing.

Others suspected an intruder. Fall River had experienced a series of break-ins that summer. Perhaps a burglar had entered the house, been surprised by Abby, killed her, then waited for Andrew to return home. But nothing was stolen. The doors were locked. No one saw a stranger entering or leaving the property. The violence seemed personal, not random.

Some historians have suggested William Borden, an illegitimate son Andrew allegedly fathered years earlier. If this person existed and learned of his parentage, might he have sought revenge against the father who never acknowledged him ? But no concrete evidence of such a person has ever emerged. The theory remains pure speculation.

Another theory focused on Emma, Lizzie’s older sister. Though Emma was supposedly fifteen miles away in Fairhaven, some wondered if she could have returned secretly, committed the murders, and left again undetected. But Emma’s alibi was solid. Friends confirmed she had been with them all morning. She had no opportunity to commit the crimes.

The most persistent alternative theory suggests Lizzie and Emma acted together. Perhaps they planned the murders jointly, with Emma providing an alibi while Lizzie carried out the deed. After their acquittal, the sisters’ relationship eventually deteriorated. They quarreled bitterly and separated in 1905. Some have speculated guilt and recrimination finally drove them apart. But again, this remains speculation without proof.

The Evidence That Haunts

Certain details of the case continue to trouble even those who believe in Lizzie’s innocence. The timing, for instance, raises profound questions.

Abby was killed first, probably around 9:30 in the morning. She died upstairs in the guest room, struck nineteen times from behind. Her body lay undiscovered for at least ninety minutes.

During that hour and a half, someone was in the house with a corpse. Andrew came home around 10:45. He lay down on the sofa for a rest. And then, around 11:00, he too was attacked—struck eleven times in the face while he lay sleeping.

If Lizzie was innocent, where was she during this time ? She claimed to have been downstairs, then in the yard, then in the barn. Yet she never saw or heard anything suspicious. She never encountered the killer. She never discovered Abby’s body upstairs.

The killer, meanwhile, would have had to enter the house undetected, murder Abby, hide somewhere for ninety minutes while Andrew came home and Lizzie moved about the house, then murder Andrew, and finally escape—all without being seen by Lizzie, Bridget, or any neighbors.

It strains credibility.

Then there was the matter of the locked doors. The house’s front door had a special lock that required a key from both inside and outside. Andrew Borden was obsessive about security. He kept the doors locked even during the day.

When Andrew returned home that morning, he found the door locked. He struggled with it for several minutes while Bridget came to let him in. If an intruder had been in the house, how did they enter through locked doors ? How did they leave ?

The absence of blood on Lizzie’s clothing also cuts both ways. It suggests her innocence—how could she commit such violent murders without getting blood on herself ? But it also raises another question: what happened to the killer’s bloody clothes ?

Medical experts testified that both victims bled extensively. The killer would have been spattered with blood. Yet no bloody clothing was ever found. Not in the house, not in the yard, not anywhere.

If Lizzie was guilty, she had roughly fifteen minutes between killing her father and the arrival of neighbors to dispose of bloody clothes, clean herself completely, hide the murder weapon, and compose herself. Possible, perhaps, but extraordinarily difficult.

The Prussic Acid

One detail that has never been satisfactorily explained was Lizzie’s attempt to purchase poison the day before the murders. On August 3, Lizzie visited a local drugstore and asked to buy prussic acid—one of the deadliest poisons known.

When the druggist asked what she needed it for, Lizzie explained she wanted to clean a sealskin cape. The druggist refused the sale. Prussic acid was not used for cleaning fur, and selling it without a prescription was illegal.

At trial, the prosecution tried to introduce this evidence to show premeditation. If Lizzie had planned to poison her parents but failed to obtain the poison, she might have turned to a more brutal method. But the judge ruled the evidence inadmissible. The attempt to buy poison happened before the alleged crime, he reasoned, and could not prove Lizzie intended to commit murder.

Defenders of Lizzie’s innocence argue the timing was coincidental. Perhaps she truly did want to clean a cape. Perhaps she was simply ignorant about proper cleaning methods. The fact that she asked openly, in a public drugstore where people knew her, suggests she had no criminal intent. A calculated poisoner would have been more discreet.

But the timing troubles many. One day before her parents were killed, Lizzie tried to obtain a deadly poison. Whether coincidence or premeditation, it remains one of the case’s most disturbing details.

The Burned Dress

Three days after the murders, Emma witnessed Lizzie burning a dress in the kitchen stove. When questioned about it later, both sisters explained the dress had been stained with old paint and was ready to be discarded.

At trial, Emma supported this explanation. She testified the dress was old and faded. Burning it was perfectly reasonable. The prosecution never proved the burned dress was the one Lizzie had worn on the morning of the murders.

But the optics were devastating. Three days after her parents were brutally killed, with police searching for evidence, Lizzie destroyed a piece of her clothing. Even if the dress was innocent, the timing appeared damning.

Critics of the verdict point to this as consciousness of guilt. An innocent person, they argue, would have preserved every piece of evidence that might help clear her name. Only someone with something to hide would destroy potentially relevant clothing while under investigation.

Supporters counter that Lizzie was simply cleaning out old things, a normal household activity. She had no reason to think one old dress would become evidence. The fact that she burned it openly, in front of her sister and a guest, suggests she had nothing to hide.

The truth, like so much in this case, remains elusive.

The Cultural Impact

The Lizzie Borden case transcended its immediate facts to become a cultural touchstone in American life. Within weeks of the murders, a rhyme began circulating—a darkly playful verse that children still recite more than a century later:

Lizzie Borden took an axe

And gave her mother forty whacks

When she saw what she had done

She gave her father forty-one

The rhyme is factually inaccurate—Abby received nineteen blows, Andrew eleven—but accuracy mattered less than the sinister rhythm. The verse captured something essential about the case: a daughter accused of killing her parents with shocking violence.

The case also became a lightning rod for debates about gender, class, and justice. Could a respectable woman commit such savage violence ? Should juries judge women by different standards than men ? Did Lizzie’s social standing and respectability shield her from proper scrutiny ?

These questions resonated because they touched on deep anxieties in American society during the 1890s. Women were beginning to challenge traditional roles. The women’s suffrage movement was gaining strength. Working-class immigrants were flooding into cities. Old certainties about gender, class, and social order were crumbling.

Lizzie Borden became a symbol for all these tensions. To some, she represented innocent womanhood persecuted by a rush to judgment. To others, she embodied the dangerous potential of women who rejected their proper place.

The Media Circus

The Borden case was one of the first true media spectacles in American history. Newspapers across the country covered every development. Reporters camped outside the courthouse. Artists sketched courtroom scenes. The public devoured every detail.

The coverage was not neutral. Some newspapers portrayed Lizzie as a victim of circumstantial evidence and gender prejudice. Others all but declared her guilty before the trial began. The Boston Globe published elaborate diagrams of the house. The New York Times sent multiple reporters to cover the trial.

This media attention shaped public perception in ways that made a fair trial nearly impossible. By the time the jury was selected, virtually everyone in Massachusetts had formed an opinion. The case had become less about facts and evidence than about narratives and symbols.

The sensational coverage also set a template that continues today. The Borden case pioneered the true crime genre that now dominates podcasts, television, and books. It established the pattern: a shocking crime, a mysterious defendant, conflicting evidence, and a trial that captivates the nation.

The House on Second Street

The Borden house still stands at 92 Second Street in Fall River. After Lizzie and Emma moved to their new home on the Hill, the property changed hands several times. In 1996, it was purchased and converted into a bed and breakfast and museum.

Today, visitors can tour the rooms where the murders occurred. They can see the sofa where Andrew died. They can stand in the guest room where Abby fell. They can sleep in the same house where two people were brutally killed on an August morning in 1892.

The museum has become a pilgrimage site for true crime enthusiasts. Thousands visit each year. Some come seeking thrills. Others hope to solve the mystery that has eluded investigators for more than a century.

The house offers tours, historical presentations, and even overnight stays for the truly dedicated. Guests report strange occurrences—unexplained sounds, cold spots, objects moving on their own. Whether these experiences reflect genuine paranormal activity or the power of suggestion, they demonstrate how thoroughly the Borden murders have permeated American consciousness.

The case refuses to die. Each generation rediscovers it, reexamines the evidence, and reaches its own conclusions.

Modern Analysis

In recent decades, forensic experts and historians have reexamined the Borden case using modern investigative techniques. Some of their findings have added new dimensions to the old mystery.

Blood spatter analysis, for instance, suggests the killer stood close to both victims. The attacker would have been covered in blood—on hands, face, arms, and clothing. This makes Lizzie’s clean appearance immediately after the murders even more puzzling.

Some experts have theorized Lizzie could have stripped naked before committing the murders, then washed thoroughly afterward. But this would have required extraordinary nerve and planning. It also would have left evidence—wet towels, water stains, discarded clothing. None were found.

Psychological profilers have analyzed Lizzie’s behavior and statements. Her flat affect after the murders could indicate shock, as the defense argued. Or it could suggest a personality capable of extreme violence without remorse. Without the ability to interview her directly, definitive conclusions remain impossible.

Historical researchers have also uncovered new details about the Borden family dynamics. Andrew was even more controlling and miserly than initially reported. The tensions between Lizzie and Abby ran deeper than simple stepmother-stepdaughter conflict. Money disputes had created a toxic atmosphere in the household for years.

These findings paint a picture of a deeply dysfunctional family. But dysfunction is not proof of murder. Thousands of families endure similar tensions without anyone resorting to violence.

The Verdict of History

The legal system declared Lizzie Borden not guilty. That verdict stands. No new trial can be held. She cannot be tried again for the same crime. Double jeopardy protections ensure that.

But the court of public opinion has never been so certain. Polls conducted over the years consistently show most Americans believe Lizzie was guilty. The phrase “Lizzie Borden took an axe” has become shorthand for getting away with murder.

This disconnect between legal verdict and popular belief raises important questions about justice. Should we respect the jury’s decision, even when we personally disagree ? Does acquittal mean innocence, or merely that the prosecution failed to prove guilt ?

The American legal system is built on the principle that it is better for guilty people to go free than for innocent people to be convicted. Proof beyond a reasonable doubt is a high standard, deliberately so. The Borden jury applied that standard and found it had not been met.

We can disagree with their conclusion. We can examine the evidence and reach different verdicts in our own minds. But we must also acknowledge that twelve citizens, who heard all the testimony and saw all the evidence firsthand, decided the prosecution had not proven its case.

That is how the system is supposed to work.

The Unanswered Questions

More than 130 years after the murders, fundamental questions remain unanswered. If Lizzie was innocent, who killed Andrew and Abby Borden ? How did the killer enter and exit a locked house without being seen ? Where did the murder weapon go ? What happened to the killer’s bloody clothing ?

If Lizzie was guilty, how did she commit such violent murders without leaving any physical evidence ? How did she clean herself so thoroughly in such a short time ? Why did she remain in Fall River, living among people who believed she had gotten away with murder ?

We will likely never know the answers. Everyone directly connected to the case is long dead. No new evidence is likely to emerge after so many years. The mystery has become permanent.

Perhaps that is why it endures. The Lizzie Borden case offers no easy answers. It cannot be neatly resolved. It forces us to grapple with ambiguity, with the limits of knowledge, with the difference between legal innocence and actual innocence.

The Woman Behind the Mystery

Lost in all the speculation and analysis is the human being at the center of the story. Lizzie Andrew Borden lived sixty-six years. Only one day of those years involved the murders for which she is remembered.

Before August 4, 1892, she was a quiet Sunday School teacher, devoted to her church and charitable causes. After June 20, 1893, she was a wealthy woman trying to live quietly despite notoriety she could never escape.

She attended theater performances. She developed an interest in breeding Boston terriers. She made a few friends who believed in her innocence. She tried, as much as possible, to live a normal life.

But she could never be normal. Everywhere she went, people whispered. Former friends crossed the street to avoid her. Children sang the rhyme about her as she passed. She was simultaneously the most famous and most isolated woman in Fall River.

What must that have been like ? To be legally innocent but socially condemned ? To know that most people believed you had murdered your own parents ? To live every day under that shadow ?

If she was innocent, the injustice is profound. An innocent woman spent thirty-four years ostracized by her community for crimes she did not commit. The real killer went free while she bore the blame.

If she was guilty, the punishment may have been worse than prison. She had wealth but no acceptance. She had freedom but no peace. She lived every day knowing what she had done, unable to confess, unable to repent, unable to escape.

Either way, it was a terrible fate.

The Final Days

Lizzie Borden died on June 1, 1927, at her home in Fall River. Pneumonia had weakened her for weeks. She was sixty-six years old.

Her funeral was small and private. Few attended. The newspapers noted her passing, reminding readers of the thirty-five-year-old scandal that had made her famous.

Nine days later, Emma died in Newmarket, New Hampshire. She was seventy-six. The sisters had not spoken in more than twenty years. Whatever secrets they shared, whatever truths they knew about that August morning in 1892, they took with them.

Both women were buried in the family plot in Oak Grove Cemetery in Fall River. They rest near their father Andrew and stepmother Abby—the same people whose deaths had defined their lives.

The gravestone is simple. No mention of the trial, the accusations, the notoriety. Just names and dates. The stone says nothing about guilt or innocence.

Perhaps that is fitting. In the end, we are all reduced to names and dates. The complexities of our lives, the ambiguities of our choices, the mysteries we carry—all fade away.

Only the questions remain.

Why We Still Care

The Lizzie Borden case should be a historical footnote. A 19th-century murder, a controversial trial, a verdict rendered more than 130 years ago. Why does it still captivate us ?

Part of the answer lies in the mystery itself. We are drawn to unsolved puzzles. The case presents evidence pointing in multiple directions, allowing each person to play detective and reach their own conclusion.

But the deeper appeal is what the case reveals about justice, truth, and certainty. The Borden trial reminds us that legal innocence and actual innocence are not always the same thing. It demonstrates that we can never know another person completely. It shows that some questions have no answers, no matter how desperately we seek them.

In an age that demands certainty, that insists every question must have a definitive answer, the Lizzie Borden case offers something different. It embraces ambiguity. It acknowledges doubt. It accepts that some mysteries remain forever beyond our understanding.

The jury said Lizzie Borden was not guilty. They followed the law and applied the proper standard of proof. Their verdict deserves respect.

But respect for the verdict does not require us to stop asking questions. It does not demand we abandon our own analysis. It does not mean the mystery is solved.

Lizzie Borden was found not guilty. The law declared her innocent. But America never quite believed it. And more than a century later, we are still trying to understand what really happened on that sweltering August morning in Fall River, Massachusetts.

The truth died with Lizzie on June 1, 1927. All that remains is the mystery. And that, perhaps, is why we cannot let it go.