November 12, 2025. A Wednesday morning in Michigan.

John Skelton, fifty-three years old, was counting down the days. Seventeen more days until his release from Bellamy Creek Correctional Facility. Seventeen days until he’d walk out of the prison gates after fifteen years behind bars.

He’d been denied parole multiple times over the years. But his sentence was finally ending. November 29, 2025—that was his release date. Just over two weeks away.

John had plans, presumably. A future beyond prison walls. Whatever life looks like for a man who spent fifteen years locked up for unlawful imprisonment of his own children.

But on that Wednesday morning, everything changed.

Michigan State Police announced new charges against John Skelton. Not parole violations. Not technicalities that might delay his release.

Murder. Three counts of open murder. Three counts of tampering with evidence.

The victims? His three sons—Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner—who vanished fifteen years ago during a Thanksgiving weekend visit and were never seen again.

For fifteen years, John maintained the boys were alive. Fifteen years of changing stories, underground organizations, mysterious strangers. Fifteen years of their mother, Tanya Zuvers, searching for answers while John sat in prison on lesser charges.

Now, just seventeen days before his scheduled release, prosecutors were saying something different. Not kidnapping. Not unlawful imprisonment.

Murder.

This is the story of three little boys who disappeared on Thanksgiving weekend 2010, a father whose explanations never quite added up, and a mother who fought for fifteen years to hear the word “murder” attached to the man she believes took her children forever.

Thanksgiving 2010

Morenci, Michigan, is the kind of small town where everyone knows everyone. Population just over two thousand. The kind of place where kids ride bikes down quiet streets, where doors are left unlocked, where neighbors wave to each other at the grocery store.

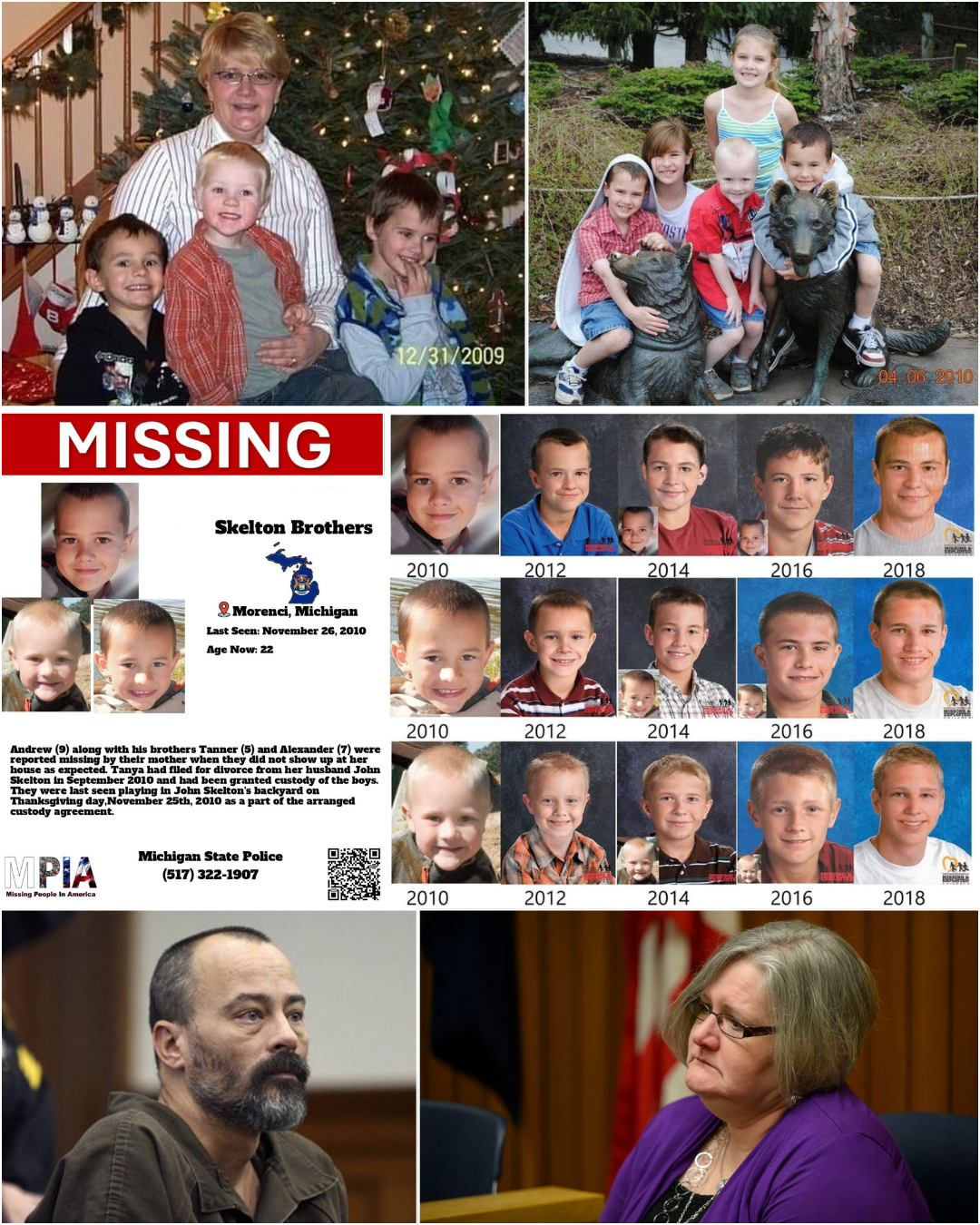

In November 2010, Tanya Zuvers and John Skelton were recently divorced, navigating the complicated terrain of shared custody. They had three sons together: Andrew, nine years old; Alexander, seven; and Tanner, just five.

The boys were typical kids. Andrew wore glasses, had a scar on his chin, loved his brown pajamas with orange trim. Alexander was quieter, smaller, wore black pajama pants and grey shirts. Tanner, the youngest, had strawberry blond hair and adored Scooby-Doo—he even had a Scooby-Doo shirt he wore constantly.

That Thanksgiving, the boys were with their father for a court-ordered visitation. They’d spent Thanksgiving Day with John at his home in Morenci. The plan was simple: John would return them to Tanya on Friday, November 26, the day after Thanksgiving.

But Friday morning came and went. The boys didn’t show up.

Tanya tried calling John. No answer. She called again. Still nothing. By afternoon, panic was setting in.

She drove to John’s house. His car was gone. The house was quiet. No sign of him or the boys.

Tanya called the police. Something was wrong. John wasn’t answering. The boys should have been home hours ago. This wasn’t like him—despite their custody battles, he’d always followed the court orders before.

When police finally located John, they found him at the hospital. He’d broken his ankle—not in an accident, but in a failed attempt to take his own life.

At his home, investigators found a rope hanging from the stairwell banister. Tow straps scattered around. Evidence of a suicide attempt that hadn’t succeeded.

But John’s failed suicide wasn’t the most alarming discovery. It was what he said when investigators asked the only question that mattered: Where are your sons?

The Stories That Never Made Sense

John’s first story was simple. He’d given the boys to friends. They were safe. They’d be returned soon.

When police pressed for details—names, addresses, contact information—the story changed.

Actually, John said, he’d given them to a woman he’d met online years before. Her name was Joann Taylor. She was married to a pastor named Mark. They lived somewhere in Jackson County or maybe Hillsdale, Michigan—John wasn’t quite sure which. She drove a white or silver minivan.

Joann was supposed to return the boys to Tanya, John explained. He’d been planning to take his own life—he didn’t want his children to find him. So he’d arranged for Joann to keep them safe and return them to their mother.

Police immediately launched an investigation. An Amber Alert went out for three missing boys, last seen wearing their pajamas. Andrew in brown with orange trim. Alexander in black pants and a grey shirt. Tanner in camouflage pants and his beloved Scooby-Doo shirt.

Investigators searched databases, contacted social services, reached out to churches and pastors across the region. They were looking for anyone named Joann Taylor married to a pastor named Mark who might have contact with John Skelton.

They found nothing. No Joann Taylor. No pastor named Mark. No white or silver minivan.

The woman John described didn’t exist.

When confronted, John’s story evolved again. This time, from his hospital bed, he told investigators about an underground organization. A group that helped protect children. He’d given Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner to this group because he believed they needed protection.

From what? From their mother, John claimed. He alleged Tanya had been abusing the boys, though he’d never reported this to authorities and no evidence could be found to support the claim.

The underground group, John insisted, had the boys. They were alive. But they wouldn’t be returned as long as Tanya had custody.

Which underground group? Investigators wanted to know.

At a December 2010 hearing, John provided more details. The organization was called “United Foster Outreach and Underground Sanctuaries.” It was connected to Amish communities, he said. They specialized in hiding children from dangerous situations.

Police immediately began investigating. They contacted Amish communities across Michigan, Ohio, and Indiana. They searched for any organization matching the name John had given.

Again, they found nothing. No such organization existed. No Amish group had any knowledge of three missing boys or a man named John Skelton.

Then John claimed he’d had a vision. In this vision, he saw his sons in a dumpster in Ohio. He provided enough detail that investigators took it seriously, searching dumpsters in the area John indicated.

They found nothing.

In 2018, eight years into his prison sentence, John spoke to local media with yet another version. This time, he claimed he’d given the boys to two women and a man in a light-colored van. They’d planned to take Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner to a farm along the Ohio-Indiana border.

He also insisted that investigators needed to speak with Mose Gingerich, a reality television star and author who’d left the Amish community. Gingerich, John claimed, could bring the boys back.

Police tracked down Gingerich. He’d never heard of the Skelton family or the missing boys. But he agreed to visit John in prison, hoping to get answers.

When Gingerich arrived, John became visibly shaken. He wouldn’t provide useful information. The meeting ended with more questions than answers.

Every story John told had one thing in common: the boys were alive, somewhere, with someone. And every story fell apart under investigation.

What The Evidence Actually Showed

While John’s stories kept changing, investigators were building a timeline based on facts, not fiction.

Cell phone records showed John’s phone pinged in Morenci, Michigan—his hometown—on the early morning of November 26, 2010. The last day anyone saw the boys alive.

Then his phone pinged in Holiday City, Ohio, approximately twenty-five miles southwest of Morenci. The phone stayed active in that Ohio location for over two hours before going silent.

When it pinged again, John was back in Morenci.

Two hours. Two hours unaccounted for in a location across the state line. Two hours when John’s phone wasn’t moving, wasn’t making calls, just sitting somewhere in Holiday City, Ohio.

Traffic camera footage corroborated the cell data. John’s blue Dodge Caravan, Michigan license plate 9JQ H93, was spotted on the Ohio Turnpike near the Michigan-Ohio border. The timestamps showed the van traveling southwest between 4:29 AM and 6:46 AM on November 26.

Four in the morning. While most of Morenci was asleep, John Skelton was driving three boys in their pajamas across state lines into Ohio.

But the most damning evidence came from John’s internet search history.

Before his sons went missing, John had searched online for “how to break a neck”.

Not an accident. Not a medical question. Not research for a book or curiosity about anatomy. A specific, deliberate search about causing fatal injury.

Investigators also found something else in John’s home after the boys vanished. Along with the rope and tow straps from his suicide attempt, they found a note.

“You will hate me,” it read.

Not “I’m sorry.” Not “Forgive me.” Not “I couldn’t go on.”

“You will hate me.”

The kind of message someone leaves when they’ve done something unforgivable. Something that goes beyond taking your own life. Something that involves other people—people who will discover what you’ve done and never forgive you for it.

The Custody Battle That Preceded Everything

To understand November 2010, you have to go back to September.

John and Tanya’s divorce had been contentious. Most divorces involving children are. But this one had an added layer of complication.

Tanya had a past. In 1998, when she was thirty-two years old, she’d pleaded guilty to misdemeanor fourth-degree criminal sexual conduct involving a fourteen-year-old boy. She’d served her sentence and was registered as a sex offender.

John used this against her in custody proceedings. He argued she shouldn’t have custody of their sons. He asked the court to sever her parental rights entirely.

The court didn’t agree. Despite Tanya’s past, there was no evidence she posed any danger to her own children. The boys showed no signs of abuse. Teachers, family members, social workers—no one reported concerns. The court maintained joint custody.

But John wasn’t done fighting. In mid-September 2010, just two months before Thanksgiving, he withdrew Andrew and Alexander from school.

He told school officials they were going on vacation. He also hinted that he might need their school records forwarded. The implication was clear: John might not be bringing the boys back to Morenci.

Then he drove them to Florida. Without Tanya’s knowledge. Without court permission. In direct violation of their custody arrangement.

When Tanya found out, she went to Florida. With the help of local authorities, she forced John to return the boys. He complied, but only under threat of arrest.

That’s when Tanya filed for divorce finalization and full custody. The custody battle intensified. Court dates were scheduled. Lawyers were involved. The situation was escalating.

And then came Thanksgiving. The last court-ordered visitation before the next custody hearing.

John had the boys for one day. Thanksgiving Day. He was supposed to return them the next morning.

Instead, at four in the morning, he loaded them into his blue Dodge Caravan and drove toward Ohio.

A Mother’s Fifteen-Year Fight

Tanya Zuvers has lived in a special kind of hell for fifteen years. The hell of not knowing.

She knows her sons aren’t coming home. Deep down, she’s known since that November morning when John couldn’t produce them, when his stories kept changing, when the Amber Alert went out and days turned into weeks with no sightings.

But knowing and having it confirmed are two different things. And for fifteen years, John maintained—through changing stories and implausible explanations—that the boys were alive somewhere.

How do you grieve when there are no bodies? How do you move forward when there’s no funeral, no grave, no place to visit your children?

In 2023, thirteen years after her sons vanished, Tanya made a painful decision. She petitioned the Lenawee County Probate Court to declare Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner legally deceased.

The hearings stretched into 2024. John, from prison, fought against the declaration. His story remained the same: the boys were alive, just hidden by protective organizations.

In March 2025, a judge finally ruled. Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner Skelton were legally dead.

But the judge declined to rule on something else Tanya had requested: a declaration that John Skelton had murdered her children.

There wasn’t enough evidence, the judge said. Without bodies, without definitive proof of death beyond the passage of time, the court couldn’t make that determination.

It was a partial victory that felt like defeat. Yes, her sons were legally gone. Yes, she could finally grieve openly without the pretense that they might walk through the door someday. But the man she believed killed them—the man whose stories never made sense, whose phone pinged in Ohio for two hours, who searched “how to break a neck” before they disappeared—wasn’t officially their murderer.

Tanya had to watch as John’s release date approached. November 29, 2025. Just weeks away. He’d serve his full sentence for unlawful imprisonment and walk free.

Free, while her sons were gone forever.

Then came November 12, 2025.

The Charges That Changed Everything

The announcement from Michigan State Police was brief but seismic.

John Russell Skelton, currently incarcerated at Bellamy Creek Correctional Facility, has been charged with three counts of open murder and three counts of tampering with evidence. The dates of the alleged offenses: November 25, 2010—the last time Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner Skelton were seen alive.

“Open murder” in Michigan means prosecutors aren’t specifying first-degree or second-degree murder at the charging stage. They’re leaving it open for a jury to decide which degree fits the evidence. It’s a prosecutorial strategy that allows flexibility as the case develops.

Tampering with evidence—three counts, one for each boy—suggests prosecutors believe John not only caused their deaths but deliberately hid what he’d done. Destroyed evidence. Concealed bodies.

The timing was stunning. Two weeks before his scheduled release. Seventeen days.

For fifteen years, John had been in prison on lesser charges. For fifteen years, investigators had been building the murder case, receiving tips, following leads, searching for the bodies that would provide definitive proof.

They never found the bodies. But they found enough.

Tanya released a statement through her attorney. Her words were measured but carried the weight of fifteen years of grief:

“This development marks a significant moment in a long and painful journey. While I understand the public interest in this case, I ask that my family’s privacy be respected as we process this news and continue to grieve the loss of Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner.”

She called the charges a development that left her family “shocked and heartbroken all over again”.

Shocked—even though this was what she’d been hoping for. Heartbroken—even though this was justice she’d fought for.

Because murder charges, even when they’re what you’ve wanted for fifteen years, mean accepting that your children are really gone. That the stories about underground organizations and protective Amish groups and mysterious strangers were all lies. That the man who fathered your children did the unthinkable.

The Investigation That Never Stopped

For fifteen years, while John Skelton sat in prison telling his stories, investigators never stopped working the case.

Michigan State Police took over as the lead agency in 2013, three years after the boys vanished. Before that, it had been a collaboration between the Morenci Police Department—a small-town force with limited resources—and the FBI.

The case was officially reclassified as a homicide investigation in 2011, just months after the boys disappeared. Everything investigators had uncovered pointed in one direction: Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner were not alive, and their father knew exactly what had happened to them.

But knowing and proving are different things. Especially when there are no bodies.

The cell phone data was compelling. John’s phone pinged in Holiday City, Ohio, for over two hours on the morning the boys vanished. Traffic cameras confirmed his blue Dodge Caravan crossed into Ohio around 4:30 AM.

But Holiday City is a small unincorporated community. It’s rural, with wooded areas, farmland, properties where someone could hide something—or someone—without being noticed.

Investigators searched. They brought in cadaver dogs, ground-penetrating radar, volunteers who combed through brush and fields. They focused on areas within the cell tower range that pinged John’s phone that morning.

They searched dumpsters, following up on John’s “vision.” They searched properties near the Ohio-Indiana border, following up on his claim about a farm. They even searched in Montana after remains of three children were found in a shed there in 2017—but forensics ruled those children out.

Every search came up empty.

Without bodies, building a murder case is extraordinarily difficult. Prosecutors need to prove beyond reasonable doubt that the victims are dead and that the defendant caused their deaths. It’s called a “no-body” homicide, and while they’ve been successfully prosecuted, they require overwhelming circumstantial evidence.

For years, prosecutors didn’t believe they had enough. Yes, John’s stories were lies. Yes, his phone placed him in Ohio. Yes, his internet searches were damning. But defense attorneys are skilled at creating reasonable doubt, and “my client gave the children to someone else, and that person harmed them” is exactly the kind of alternative theory that can sway a jury.

So investigators kept working. They re-interviewed witnesses. They analyzed John’s prison communications—phone calls, letters, visitor logs. They consulted with experts in deception analysis, child abduction, and homicide investigation.

They waited for John to slip up, to tell someone something, to provide a detail that would lead them to the boys.

And they prepared for the day when they’d have enough to charge him with murder, even without bodies.

That day came in November 2025, just seventeen days before John was scheduled to walk free.

What The Internet Searches Revealed

Among all the evidence investigators collected, perhaps the most chilling were John’s internet searches in the days and weeks before his sons vanished.

“How to break a neck”.

The search was specific. Clinical. Not “neck injuries” or “spinal cord damage” or the kind of general medical query someone might make out of curiosity. This was a search about method. About how to cause a specific, fatal injury.

Investigators also found searches about children and drowning, though specific details haven’t been publicly released. The pattern suggested someone researching methods of causing death.

Then there were searches about body disposal. About how long it takes for remains to decompose in different environments. About whether bodies float or sink.

These weren’t academic searches. They weren’t research for a book or morbid curiosity. They were the searches of someone planning something terrible and trying to understand the aftermath.

The timing matters. These searches occurred in the weeks leading up to Thanksgiving 2010. While John was in the middle of a custody battle with Tanya, while court dates were being scheduled, while he was losing legal ground in his fight to keep the boys from their mother.

When investigators found the suicide note—”You will hate me”—alongside evidence of John’s internet activity, a picture emerged. Not of a desperate father trying to protect his children from an abusive mother, as John claimed. But of a man who’d decided that if he couldn’t have his sons, no one would.

The Psychology of Family Annihilation

Experts in family violence have a term for what investigators believe John Skelton did: family annihilation.

It’s a specific type of familicide where a parent—usually a father—kills his children and sometimes his spouse, often in the context of a divorce or custody dispute. The psychology is complex, but it typically involves a toxic combination of narcissism, control, and revenge.

For these perpetrators, children aren’t seen as independent people. They’re extensions of the parent, possessions in a sense. When a custody battle is lost, when a spouse moves on, when control is slipping away, killing the children becomes a way to hurt the other parent in the most devastating way possible.

“If I can’t have them, you can’t either”.

Often, these perpetrators also attempt or complete suicide afterward. In their minds, the family unit no longer exists, so there’s no reason for them to continue living. The suicide attempt isn’t about guilt or remorse—it’s about the destruction of their perceived family structure.

John’s suicide attempt fits this pattern. The rope found hanging from his stairwell banister. The broken ankle from jumping. The note: “You will hate me”.

But unlike many family annihilators who succeed in taking their own lives, John survived. And surviving created a problem: he had to explain where his sons were.

Hence the stories. The ever-changing, increasingly implausible stories about Joann Taylor and underground organizations and Amish groups. Stories designed to suggest the boys were alive, just hidden, just out of reach.

Because admitting what he’d done would mean facing not just the legal consequences but also the judgment he referenced in his note. The hatred he knew would come.

A Small Town’s Vigil

Morenci, Michigan, has never forgotten the Skelton brothers.

In a town of just over two thousand people, the disappearance of three children isn’t a news story that fades. It’s a wound that stays open, a loss the entire community carries.

For years, residents held annual vigils on the anniversary of the boys’ disappearance. They’d gather at a local park, light candles, display photos of Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner. Some people brought the boys’ favorite toys—action figures, stuffed animals, things that might have made them smile.

Tanya would attend, when she could bear it. Standing in front of neighbors and friends, many of whom had known her sons, many of whom had watched them grow before they vanished. The community support meant everything to her, even as the grief felt unbearable.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children released age-progression photos in 2020, showing what the boys might look like a decade after their disappearance. Andrew at nineteen, preparing for college. Alexander at seventeen, nearly an adult. Tanner at fifteen, a teenager.

The images circulated through Morenci, posted in store windows, shared on social media. Everyone knew the boys were likely gone, but seeing those age-progressed faces—imagining them growing up, becoming young men—kept hope alive in a way that felt both necessary and heartbreaking.

When the news broke on November 12, 2025, that John had been charged with murder, Morenci reacted with a mixture of relief and renewed grief.

Relief because justice, after fifteen years, might finally come. Relief because Tanya might finally get the acknowledgment she’d fought for: that her sons were taken from her, that John was responsible.

But renewed grief too. Because murder charges mean accepting what everyone had known but hadn’t wanted to believe. That Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner aren’t coming home. That those age-progression photos will never match reality. That three little boys died on a cold November morning in 2010, far from home, in circumstances no child should ever face.

Where Are The Boys?

This is the question that haunts everyone who’s followed the case. If John killed his sons, what did he do with their bodies?

The cell phone data places him in Holiday City, Ohio, for over two hours. Traffic cameras show his van on the Ohio Turnpike heading southwest from Michigan between 4:29 AM and 6:46 AM.

Holiday City is rural. It’s the kind of area with woods, streams, abandoned properties, places where someone could hide something without being observed. Especially at four in the morning, when most people are asleep.

Investigators have focused searches in that area, but Holiday City falls within a broad cell tower range. John could have been anywhere within several miles of that tower. And in rural Ohio, several miles encompasses a lot of ground.

Some investigators believe the boys are in water—a river, a creek, a pond. Bodies in water are notoriously difficult to find, especially after years have passed. Scavenger animals, water currents, decomposition—all these factors can scatter remains or hide them in places searchers would never think to look.

Others believe John buried them somewhere on private property. A wooded lot, a farm field, somewhere he could dig in the pre-dawn darkness without being seen. The problem with this theory is time—two hours isn’t long to dig three graves deep enough to hide bodies. But it might be long enough for shallow graves, or for concealing bodies in an existing structure.

There’s also the possibility that John hid the boys’ remains in his van initially, then disposed of them elsewhere later. But this theory has problems too. John was hospitalized immediately after the boys vanished. Investigators seized his van. If remains had been in the vehicle, forensics would have found evidence.

The most likely scenario, based on the evidence, is that John took his sons to a location in Ohio during those two hours, and their remains are still there. Somewhere in the rural areas around Holiday City, in woods or water, three little boys wait to be found.

John knows. He’s the only person who knows. And for fifteen years, he’s refused to tell anyone.

The Grandmother Who Believes

Not everyone believes John is guilty.

Roxann Skelton, John’s mother, has maintained throughout the investigation that her son didn’t harm his children. She believes his stories about giving the boys to protective organizations. She believes they’re alive somewhere.

It’s a position that’s earned her criticism from the public and isolation from many in Morenci who believe John is guilty. But Roxann remains steadfast.

To her, John is a troubled man who was trying to protect his sons from what he perceived as danger. The suicide attempt, in her view, wasn’t the act of a man who’d just killed his children—it was the desperation of a father who’d given them up and couldn’t live with the separation.

She points to the lack of bodies as evidence. Fifteen years, multiple searches, countless tips—and investigators haven’t found the boys. To Roxann, this suggests they might actually be alive somewhere, hidden by people John trusted.

Most family members of perpetrators eventually come to accept their loved one’s guilt when the evidence is overwhelming. But Roxann represents a minority who cannot or will not believe. Whether it’s denial, genuine belief in John’s innocence, or a mother’s inability to accept her son could do something so terrible, her position hasn’t changed.

Now, with murder charges filed, Roxann will have to confront the justice system’s conclusion: her son is accused of murdering his three children and hiding their bodies.

How she’ll respond to a trial, to testimony about internet searches and cell phone data and lies that never held up, remains to be seen.

What Happens Next

John Skelton is no longer scheduled for release on November 29, 2025.

Instead, he faces three counts of open murder and three counts of tampering with evidence. If convicted, he could spend the rest of his life in prison.

Michigan doesn’t have the death penalty, so life imprisonment is the maximum sentence. Given that John is fifty-three years old, a life sentence would mean he’d never see freedom again.

The case will now proceed through the court system. Arraignment, preliminary hearings, potentially a trial. Prosecutors will present the evidence they’ve been building for fifteen years: the cell phone data, the internet searches, the changing stories, the note, the timeline.

John’s defense attorneys will face a difficult task. Their client has given multiple contradictory explanations for where his sons are. He’s been proven to have lied repeatedly. His internet searches are damning. His phone places him in Ohio during the crucial time period.

The defense might argue that the lack of bodies means prosecutors can’t prove the boys are dead. They might suggest alternative scenarios—that John really did give the boys to someone, and that person harmed them. They might challenge the reliability of cell phone data or argue that internet searches don’t prove intent.

But “no-body” homicide cases have been successfully prosecuted many times. Juries can infer death from circumstances, especially when those circumstances are as compelling as they are here.

The bigger question is whether John will finally tell the truth. Whether, facing life in prison, he’ll reveal where Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner are.

Some defendants, even when convicted, never reveal body locations. It’s their final act of control, their last way to hurt the families of their victims. They take that information to their graves.

Others, when faced with irrefutable evidence and no hope of acquittal, eventually confess. Sometimes out of guilt. Sometimes as part of a plea bargain. Sometimes simply because they’re tired of carrying the secret.

Which type of defendant John Skelton will be remains to be seen.

Tanya’s Journey

For Tanya Zuvers, the November 12 announcement was both vindication and devastation.

She’d spent fifteen years knowing her sons were gone, knowing John was responsible, but hearing authorities talk about “kidnapping” and “unlawful imprisonment” instead of murder.

Now, finally, the word she’d been waiting to hear: murder.

But it doesn’t bring her sons back. It doesn’t give her the chance to raise them, to watch them grow into the young men they should have become. Andrew would be twenty-four now. Alexander would be twenty-two. Tanner would be twenty.

Instead of graduations and first jobs and weddings, Tanya has memories that stop at ages nine, seven, and five. She has photos of little boys in pajamas. She has the trauma of finding out they never arrived at her house that November morning.

She’s had to navigate public scrutiny too. Her criminal record from 1998 was brought up repeatedly during custody battles and again during the investigation. People questioned whether she was a fit mother, whether John might have had legitimate reasons to fear for his sons.

But investigators found no evidence that Tanya posed any danger to her children. Teachers, family members, social workers—everyone who knew the boys reported a loving mother-son relationship. The court had maintained joint custody for a reason.

Still, the whispers followed her. The second-guessing. The awful comments online from people who knew nothing about her or her sons but felt entitled to judge.

Through it all, Tanya has maintained her focus: finding out what happened to Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner, and getting justice for them.

The murder charges represent a step toward that justice. But Tanya has been clear in her statements: justice won’t be complete until her sons are found and can be laid to rest properly.

For now, she waits. Waits for the trial. Waits for the possibility that John might finally tell the truth. Waits for closure that may never fully come.

The Legacy of Three Brothers

Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner Skelton have become more than statistics in missing children databases.

They represent every parent’s worst nightmare: children taken by someone who was supposed to protect them. They represent the failures of a system that allowed a custody battle to escalate to the point where a parent chose murder over shared custody.

Their case has been studied by law enforcement agencies across the country as an example of parental kidnapping that crosses into homicide. It’s taught in training programs about recognizing warning signs—the escalating custody disputes, the violations of custody orders, the threats and concerning behavior.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children continues to keep their case active, despite the murder charges. Until bodies are found, Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner remain officially missing.

A Facebook page, “Missing ~ Skelton Brothers, Morenci, Michigan,” keeps their story alive. It posts updates about the investigation, shares memories from people who knew the boys, and maintains hope that someday, somehow, they’ll be found and brought home.

The community of Morenci hasn’t forgotten them. Local businesses still display their photos. The annual vigils continued for years. Their story is part of the town’s history now, a dark chapter that shaped how residents think about child safety, custody disputes, and the warning signs of domestic violence.

And Tanya carries them with her every day. Not just in memory, but in her continued fight for answers, for justice, for the world to know what happened to her three little boys on a Thanksgiving weekend fifteen years ago.

The Questions That Remain

Even with murder charges filed, so much remains unknown.

Where exactly did John take his sons during those two hours in Ohio? What specific location holds the secret investigators have been searching for?

Did Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner know what was happening? Did they trust their father until the very end, or did they realize something was wrong?

Why did John do it? Was it revenge against Tanya? Fear of losing custody? A distorted belief that he was protecting his sons from something? Mental illness? Pure rage?

And the question that haunts everyone who’s followed this case: Will John ever tell the truth?

He’s maintained his lies for fifteen years. He’s changed his story multiple times but never admitted to harming his sons. Even facing murder charges, even looking at life in prison, will he finally reveal where Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner are?

Or will he take that information to his grave, exerting one final act of control over the children he couldn’t let go?

A Story Without An Ending

On November 26, 2010, three little boys disappeared from Morenci, Michigan.

Andrew, nine years old, wearing his brown pajamas with orange trim. Alexander, seven, in black pants and a grey shirt. Tanner, just five, in his beloved Scooby-Doo shirt.

They were last seen in their father’s care. Their father, who drove them across state lines in the pre-dawn darkness. Their father, who’d searched online for how to break a neck. Their father, who tried to take his own life and left a note saying “You will hate me”.

For fifteen years, John Skelton told stories. Underground organizations. Protective Amish groups. Mysterious strangers in vans. Women named Joann Taylor who didn’t exist.

And for fifteen years, investigators worked to prove what they’d known from the beginning: Andrew, Alexander, and Tanner Skelton were murdered by their father, and their bodies were hidden somewhere in rural Ohio.

On November 12, 2025, just seventeen days before John was scheduled to walk free, prosecutors finally had enough.

Three counts of open murder. Three counts of tampering with evidence. Charges that could keep John in prison for the rest of his life.

But the charges don’t answer the question that matters most to Tanya, to the community of Morenci, to everyone who’s followed this case: Where are the boys?

Somewhere in Ohio, in woods or water, in a place John Skelton visited for two hours on a November morning in 2010, three brothers wait to be found.

And until they are, this story doesn’t have an ending. Just a mother who keeps searching, a community that keeps remembering, and three little boys who deserve to come home.