The scream tore through the mountain air like a knife.

Carl Probyn was working in his garage that June morning when he heard it—a sound so primal, so filled with terror, that it turned his blood to ice. He dropped his tools and ran outside, his heart already hammering against his ribs, already knowing that something unspeakable was happening.

What he saw would haunt him for the next eighteen years.

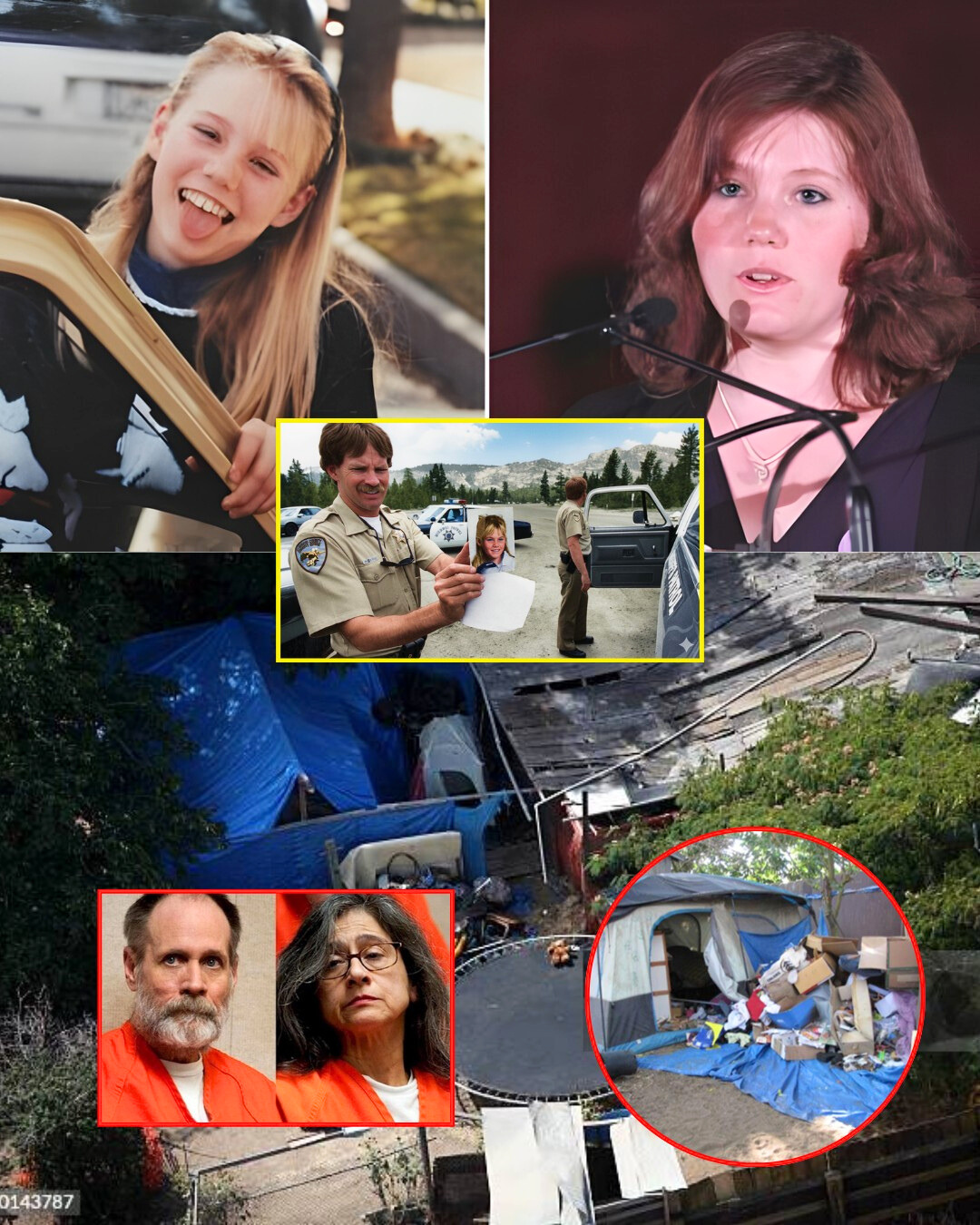

A gray sedan had pulled up beside an eleven-year-old girl in a pink windbreaker, her blonde ponytail swinging as she walked toward her school bus stop. Two people jumped out. A man grabbed the child—Jaycee Lee Dugard, Carl’s stepdaughter—and she screamed again. Then a woman stepped forward with something in her hand, and suddenly Jaycee’s small body went limp.

They threw her into the backseat like a piece of luggage.

Carl ran after them, pedaling his bicycle down the hill as fast as his legs could pump, screaming for someone—anyone—to help. But the car accelerated, its tires screeching as it disappeared around a winding mountain road in South Lake Tahoe, California.

And just like that, in broad daylight, on a quiet residential street where neighbors watered their lawns and children rode their bikes, an eleven-year-old girl vanished.

It was June 10, 1991. The date that would split one family’s life into “before” and “after.”

The Mother Who Refused to Stop Looking

Terry Probyn had kissed her daughter goodbye that morning, just like she’d done a thousand times before.

She was a single mother working as a typesetter at a print house, leaving for work early that day. Jaycee had been so excited about finishing fifth grade. She’d worn her favorite all-pink outfit—pink pants, pink top, pink windbreaker—and that butterfly-shaped ring she loved so much. Terry had watched her walk out the door, thinking about nothing more than the mundane concerns of motherhood: Did Jaycee have her lunch money? Would she remember to bring home her library book?

When Terry came home from work that afternoon, police cars lined the street.

Neighbors stood in worried clusters. Searchers combed the hillside. And her daughter—her beautiful, bright, eleven-year-old daughter—was gone.

“She was just walking to the bus stop,” Carl told her, his voice breaking. “It was less than 300 yards from our house. I saw them take her. I chased them. But I couldn’t stop them”.

The statistics were brutal, and the police didn’t sugarcoat them. Most children abducted by strangers are killed within the first few hours. After 24 hours, the chances of finding them alive plummet. After a week, hope becomes a cruel illusion that parents cling to because the alternative is unthinkable.

But Terry Probyn refused to give up hope.

Within hours of Jaycee’s disappearance, a massive search operation launched. Thousands of volunteers scoured the forests and mountains surrounding South Lake Tahoe. Helicopters circled overhead. Jaycee’s face appeared on missing children posters across California, then across the nation. The FBI joined the case. Every lead was pursued, every tip investigated.

But there were no reliable leads. The gray sedan vanished without a trace. The witnesses could provide only vague descriptions. And with each passing day, the likelihood that Jaycee was still alive diminished.

Still, Terry refused to believe her daughter was dead.

She developed what she called “survival techniques” to stay connected to Jaycee. Every night for the next 6,575 nights, Terry would step outside her home and look up at the moon. She would whisper to it, as if the moon could carry her message to wherever Jaycee was: “I’m still here, baby. I’m still waiting. Come home”.

“That’s one of my survival techniques,” Terry explained years later. “I needed to stay connected, finding something that we shared, and stayed connected with that kid. And it got me through”.

She kept Jaycee’s room exactly as it had been. She celebrated every birthday—twelve, thirteen, fourteen—setting out a cake and singing “Happy Birthday” to an empty chair. She left the porch light on every single night for eighteen years. And she never, ever spoke about her daughter in past tense.

When well-meaning friends and family members would say “Jaycee was such a sweet girl,” Terry would immediately correct them: “She IS. Not was. She IS”.

The marriage between Terry and Carl eventually crumbled under the weight of that tragedy. Carl carried his own burden of guilt. He’d been there. He’d seen it happen. He’d chased them on his bicycle and called 911 immediately. And it hadn’t mattered.

“You blame yourself,” he would later say. “You think, what if I’d been faster? What if I’d done something different?”.

But Terry never stopped looking. And two days before Jaycee was found—eighteen years later—Terry worked a double shift, came home exhausted, looked up at a full moon and said: “OK, Jaycee, where are you?”.

Her younger daughter came out to see who she was talking to.

“The moon,” Terry said. “Just the moon”.

What Terry didn’t know—what she couldn’t have imagined—was that somewhere 120 miles away, in a hidden compound behind a house in Antioch, California, Jaycee was looking at that same moon.

Into the Darkness

Inside that gray sedan on June 10, 1991, eleven-year-old Jaycee regained consciousness to find herself in the backseat.

Her body ached. Her mind reeled with confusion and terror. A woman—Nancy Garrido—sat beside her. Nancy had dragged her into the car and removed all her clothing, leaving only that butterfly-shaped ring that Jaycee would hide from them for the next eighteen years.

A blanket covered her naked body. Through gaps in the fabric, Jaycee could see glimpses of highway, of towns passing by, of normal people living normal lives just feet away from the car where she was being taken to hell.

From the front seat, she heard the driver—Phillip Garrido—laugh. “I can’t believe we got away with it,” he said to his wife.

The drive lasted three hours. Three hours during which Jaycee drifted in and out of consciousness, her small body still reeling from the stun gun that had knocked her out. Three hours during which she pleaded with them to take her home, promised she wouldn’t tell anyone, begged them to think about her mother.

They didn’t respond.

Finally, the car pulled into a driveway at 1554 Walnut Avenue in Antioch—an unremarkable house on an unremarkable street in an unremarkable California suburb. But behind that house, hidden behind fences and tarps and overgrown vegetation, was a nightmare.

Phillip Garrido had constructed a series of sheds, tents, and lean-tos in the backyard, invisible from the street, invisible even to neighbors who lived just feet away. He dragged Jaycee, her head still covered with a blanket, into this maze of structures.

He pushed her into a tiny shed—barely larger than a closet—that he’d soundproofed. Inside was a bucket for a toilet, a sleeping bag on the floor, and nothing else. He handcuffed her, leaving the eleven-year-old girl naked and terrified.

“There are trained Doberman Pinschers outside,” he told her. “If you try to escape, they will attack you and kill you”.

There were no Dobermans. But Jaycee, handcuffed and terrified in a soundproof shed, had no way of knowing that.

Garrido bolted the door from the outside. And Jaycee was left alone in the darkness.

For the next week, her only human contact was Garrido himself. He would bring her fast food—McDonald’s, Burger King—a bizarre kindness in the midst of horror. He talked to her for hours about his religious delusions, his belief that he was a “chosen servant of God,” that “demon angels” had told him to take her.

He forced her to shower with him—the first time she’d ever seen an unclothed man.

Then, one week after the kidnapping, Phillip Garrido raped eleven-year-old Jaycee Lee Dugard for the first time.

He would continue to rape her at least once a week for the next three years.

The Monster Who Hid in Plain Sight

Phillip Garrido was not unknown to law enforcement.

In 1977, he had been convicted of kidnapping a 25-year-old woman from a parking lot in South Lake Tahoe—the same town where Jaycee lived—and raping her multiple times in a Reno storage unit. The investigating officer from that case described the storage unit as a “sex palace,” featuring various sex aids, pornographic magazines and videos, stage lights, wine, and a bed.

Garrido had been sentenced to fifty years in federal prison. But he served only eleven years before being paroled in 1988. Three years later, he kidnapped Jaycee.

He met his wife Nancy while serving time at the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas. She had been visiting a relative. They married, and when Phillip was released, Nancy became his accomplice in a crime that would span nearly two decades.

Throughout Jaycee’s entire captivity, Phillip Garrido was a registered sex offender under parole supervision. Parole officers visited the Garrido home dozens of times over eighteen years. They never looked behind the fence. They never asked about the teenage girl and two young children living in the backyard. They never noticed anything amiss with the convicted rapist who had somehow acquired a family.

In April 1993, Garrido violated his parole conditions and was sent back to federal prison for four months. During his absence, Nancy kept Jaycee locked up. The system didn’t question where the girl came from or where she went while Garrido was incarcerated.

And in November 2006—three years before Jaycee was found—neighbors called 911 to report that Garrido was “a psychotic sex addict” who was living with children and had people staying in tents in his backyard.

A Contra Costa County sheriff’s deputy responded. He spent thirty minutes interviewing Garrido on his front porch. He never entered the house. He never searched the backyard. He didn’t even know Garrido was a registered sex offender, even though the sheriff’s department had that information in their system.

The deputy warned Garrido that the tents could be a code violation, then left.

Jaycee could have been rescued three years earlier. But the system failed her again.

Erasing a Name, Stealing a Life

Inside that hidden compound in Antioch, Phillip and Nancy Garrido had a plan: they would erase Jaycee Lee Dugard and replace her with someone else entirely.

When Garrido discovered that Jaycee was writing her real name in a journal about some kittens he’d given her—kittens that would later “mysteriously vanish”—he forced her to tear out the page. It was the last time Jaycee would be permitted to say or write her own name for eighteen years.

She became “Allissa”. She was never allowed to see a doctor or dentist. She was never allowed outside without supervision. Eventually, Garrido built an eight-foot fence around the backyard and erected additional tents and sheds where Jaycee lived, hidden from the world just beyond those walls.

Neighbors sometimes heard sounds. Damon Robinson lived next door to the Garridos for more than three years. In 2006, his girlfriend saw tents in the backyard and children. “I told her to call police. I told her to call right away,” Robinson said. She did call, but as we know, nothing came of it.

Other neighbors noticed the strange setup but dismissed it. “He never bothered anyone, he kept to himself,” one neighbor said. “What would we have done? You just watch your own”.

And so Jaycee remained invisible, a ghost living in plain sight in suburban California.

The Daughters Born in Captivity

In 1994, when Jaycee was fourteen years old, she realized something was wrong with her body.

She was gaining weight. She felt nauseous. She didn’t understand what was happening until Garrido told her: she was pregnant.

Pregnant. At fourteen. With her rapist’s child.

Garrido gave her no prenatal care. No vitamins. No doctor visits. Nothing. On August 18, 1994, at fourteen years old, Jaycee went into labor in that backyard compound. Nancy Garrido acted as midwife, though she had no medical training.

Jaycee gave birth to a baby girl. She named her first daughter, holding the tiny infant in her arms and feeling emotions she couldn’t begin to process.

Four years later, in 1998, the nightmare repeated. Jaycee was eighteen years old when she gave birth to her second daughter, again with no medical assistance, again in that hidden compound behind the Garridos’ house.

Two girls, born in captivity to a mother who was herself still a child when she was taken. The daughters grew up knowing only the world behind that fence. They were told that Phillip Garrido was their father and that “Allissa” was their older sister. They believed this strange, isolated existence was normal.

They never went to school. They never saw a doctor. They never played with other children. They lived in tents and wore drab-colored dresses. Their skin was unnaturally pale from lack of sunlight. They had no birth certificates, no Social Security numbers, no evidence they existed at all.

Jaycee raised them as best she could. She taught them to read using whatever books Garrido provided. She played with them in the small space they were allowed. She tried to give them some semblance of childhood, even as her own had been stolen.

And every night, when she could see the moon through a crack in the tarps, she thought of her mother Terry, 120 miles away in South Lake Tahoe, and wondered if Terry was looking at that same moon, wondering where her daughter was.

Terry was.

The Unraveling

On August 24, 2009, Phillip Garrido walked onto the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, with two young girls—aged eleven and fifteen.

He approached campus police officers Lisa Campbell and Ally Jacobs, asking permission to hold some sort of religious event on campus. He wanted to talk about his ability to control sound with his mind, about angels and demons, about God’s plan for him.

But it wasn’t Garrido’s rambling religious talk that caught the officers’ attention. It was the girls.

“There was something off,” Officer Campbell would later recall. “These girls just seemed… not right. Like they’d never been around other people before”.

The girls seemed robotic. They spoke in rehearsed phrases. They wore drab-colored dresses that looked decades out of fashion. Their skin was unnaturally pale, as if they’d never seen sunlight. They stood too close to Garrido, as if afraid to be more than a few feet from him.

When Campbell asked them questions, they said they were homeschooled by their mother and that they had a 29-year-old sister at home. Something about the entire situation felt wrong.

Officer Jacobs ran a background check on Garrido. What she discovered made her blood run cold: Phillip Garrido was a registered sex offender on federal parole for kidnapping and rape.

Why was a convicted rapist walking around a college campus with two young girls who seemed afraid and unusual?

Jacobs immediately contacted Garrido’s parole officer, Edward Santos Jr.. She reported her concerns. Santos ordered Garrido to come in for a meeting at the parole office in Concord, California, on August 26.

Garrido arrived at 2 p.m. on August 26 with his wife Nancy, the two girls, and a young woman he introduced as “Allissa”.

Parole officers began asking questions. Who were these girls? Where did they go to school? Where were their birth certificates?

“Allissa” told them the girls were her daughters. She said Garrido was a “changed man,” a “great person,” “good with her kids”. When pressed for identification, she became “extremely defensive” and “agitated,” demanding to know why she was being “interrogated”.

She claimed to be a battered wife from Minnesota hiding from an abusive husband.

But the story didn’t add up. The parole officer called the Concord police.

When a police sergeant arrived and began asking more pointed questions, the walls Phillip Garrido had built over eighteen years finally crumbled.

“I kidnapped her,” he admitted. “I raped her”.

Only then did “Allissa” speak her real name aloud for the first time in eighteen years.

“I’m Jaycee Lee Dugard”.

The Phone Call That Changed Everything

The phone call came to Terry Probyn on the afternoon of August 26, 2009.

“We found her,” the voice on the other end said. “Jaycee is alive. She’s been found.”

Terry’s knees buckled. For 6,575 days—eighteen years, two months, and sixteen days—she had looked at the moon every night and whispered to her daughter. For 6,575 nights, she had left the porch light burning. For 6,575 mornings, she had woken up to an empty house and an aching void where her daughter should have been.

And now, impossibly, miraculously, Jaycee was coming home.

“I can’t even describe it,” Terry would later say, tears streaming down her face. “It’s like… your heart has been shattered for eighteen years, and suddenly all the pieces are trying to come back together at once. But they don’t fit the same way anymore. The shape has changed”.

The news exploded across the nation within hours. The story dominated every major news network. How had an eleven-year-old girl been held captive for eighteen years, living in a backyard compound less than 200 feet from a main street, giving birth to two children with no medical care, and never been discovered?

The answers that emerged were damning.

At a press conference, Contra Costa County Sheriff Warren Rupf addressed the 2006 missed opportunity directly. “I can’t change the course of events, but we are beating ourselves up over this,” he said, his voice breaking. “We missed an opportunity to rescue Jaycee”.

Carl Probyn, Jaycee’s stepfather, was frustrated to learn that a car matching the description of the one he saw speeding away with Jaycee had been found in the yard of Garrido’s home. Nancy Garrido also fit the “dead-on” description he’d given of the woman who pulled Jaycee into the car.

“He had every break in the world,” Carl said of Garrido’s close encounters with the law.

The Reunion

The reunion took place at a police station in Concord, California.

Terry walked into a room and saw a woman—twenty-nine years old, with long blonde hair and eyes that held eighteen years of unspeakable trauma—standing there with two young girls.

This was her daughter. Her Jaycee. The eleven-year-old girl who’d left for school in a pink outfit was now a grown woman with children of her own.

Terry opened her arms. And Jaycee, after eighteen years of captivity, after eighteen years of being told she was “Allissa,” after eighteen years of being unable to say or write her own name, finally stepped into her mother’s embrace.

They held each other and wept. No words seemed adequate for that moment—the impossible reunion that Terry had prayed for but never truly believed would happen.

“I’m so sorry,” Terry whispered over and over. “I’m so sorry I couldn’t find you. I’m so sorry”.

“It’s not your fault, Mom,” Jaycee said, her voice hoarse from years of rarely speaking above a whisper. “You never stopped looking. I knew you were out there. I knew you hadn’t forgotten me”.

Standing nearby, Jaycee’s two daughters—ages eleven and fifteen, the same ages Jaycee had been when taken and when she first became pregnant—watched silently. They had been told their entire lives that “Allissa” was their older sister and that Phillip Garrido was their father. Now, suddenly, their entire reality had shifted: “Allissa” was their mother, their “father” was a kidnapper and rapist, and this crying woman was their grandmother.

The psychological damage to everyone involved was incalculable.

Jaycee was reunited with her family and said to be in good health physically, but authorities noted she was feeling guilty about developing a bond with Garrido over the years. This would later become a source of pain for Jaycee when people suggested she had Stockholm Syndrome.

Justice, Such As It Was

Phillip and Nancy Garrido were arrested immediately.

On August 28, 2009, they pleaded not guilty to a total of 29 counts, including forcible abduction, rape, and false imprisonment. Phillip Garrido appeared stoic and unresponsive during the brief arraignment hearing. His wife Nancy cried and put her head in her hands several times.

From jail, Garrido gave rambling, sometimes incoherent interviews to news media. He claimed he had not admitted to a kidnapping and that he had turned his life around since the birth of his first daughter fifteen years earlier. He spoke of “making people smile” and insisted that what he’d done would eventually be seen as a “powerful, heartwarming story”.

He was delusional until the end, unable or unwilling to comprehend the magnitude of his crimes.

In April 2011, both Phillip and Nancy Garrido pleaded guilty to avoid trial. On June 2, 2011, they were sentenced.

Phillip Garrido received 431 years to life in prison. Nancy Garrido received 36 years to life. Nancy became eligible for parole in 2029, though it’s unlikely she would ever be released.

At the sentencing hearing, Jaycee submitted a victim impact statement that was read in court.

“I chose not to be here today because I refuse to waste another second of my life in your presence,” Jaycee wrote. “Everything you ever did to me was wrong and I hope one day you can see that”.

She continued: “You stole my life and that of my family. You changed the course of the events that should have happened to an eleven-year-old girl growing up in this world”.

Terry Probyn also submitted a statement, her words raw with eighteen years of pain. “The sentence for what you did should be the death penalty,” she said. “My heart was shattered, and that void could only be filled by her”.

The Garridos were led away to spend the rest of their lives in prison. But for Jaycee and her family, the nightmare was far from over.

The Long Road to Healing

For Jaycee and her daughters, the rescue was not the end of the nightmare—it was the beginning of a different kind of struggle.

Jaycee hadn’t seen a doctor or dentist in eighteen years. She’d never learned to drive. She’d never had a job. She’d never had friends her own age. Her entire adolescence and young adulthood had been stolen, replaced by isolation, rape, and the impossible responsibility of raising two daughters in captivity.

Her daughters had never been to school. They’d never played with other children. They’d never seen a doctor. They believed the world was a dangerous place full of demons and that their “father” was protecting them. Now they had to learn that their “father” was a monster, their “sister” was their mother, and the only world they’d ever known was a lie.

The psychological rehabilitation would take years—perhaps a lifetime.

But Terry was there. After eighteen years of waiting, she finally had her daughter back. She helped Jaycee adjust to freedom. She supported her through therapy. She helped raise her granddaughters, giving them the childhood they’d been denied.

And every night, even though Jaycee was home, Terry still looked at the moon. But now, instead of whispering into the darkness, she could walk down the hall to Jaycee’s room and say goodnight in person.

In 2010, California awarded Jaycee a $20 million settlement—$8 million for Jaycee and $6 million each for her daughters—to compensate for the state’s failures in supervising Garrido. The money would help provide for their future, for therapy, for education, for the life they’d been denied.

Reclaiming Her Voice

In 2011, Jaycee published her memoir, “A Stolen Life”.

The book became a New York Times bestseller, not because of sensationalism, but because of Jaycee’s raw, honest voice. She wrote about the horror, yes, but also about survival, about raising her daughters in impossible circumstances, about the small moments of joy she managed to find even in captivity.

She wrote about the kittens Garrido gave her, how she loved them fiercely until they mysteriously disappeared. She wrote about teaching her daughters to read, about playing games with them, about trying to be the mother they needed even when she herself was still a child.

And she addressed, head-on, the concept of Stockholm Syndrome—the suggestion that she had developed affection for her captor.

“The phrase Stockholm Syndrome implies that hostages cracked by terror and abuse become affectionate towards their captors,” she said in a 2016 interview with ABC News. “Well, it’s degrading, you know, having my family believe that I was in love with this captor and wanted to stay with him. I mean, that is so far from the truth that it makes me want to throw up. I adapted to survive my circumstance”.

She explained that when she told parole officers in 2009 that Garrido was a “great person” and “good with her kids,” she wasn’t speaking from affection—she was speaking from years of conditioning, from survival instinct, from the deep-seated fear that if she said the wrong thing, her daughters would be hurt.

“I was terrified,” she said. “I didn’t know what would happen to my girls. I was protecting them the only way I knew how”.

Building Something Beautiful from the Ashes

Jaycee didn’t just survive—she thrived.

She established the JAYC Foundation (Just Ask Yourself to Care), a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping families recovering from abduction and trauma. The foundation provides support, resources, and a voice for survivors who often feel forgotten by society.

Through the foundation, Jaycee has advocated for better parole supervision, for improved training for law enforcement officers, for systems that don’t fail vulnerable people the way they failed her.

She’s given interviews, done speaking engagements, and become a powerful advocate for other survivors. But she’s also fiercely protected her privacy and that of her daughters, understanding that healing requires both speaking out and knowing when to step back.

In 2016, Jaycee sat down with Diane Sawyer for an extensive ABC News interview. She spoke about her daughters—then in their early twenties—and how they were adjusting to the world.

“They’re strong,” Jaycee said. “They’re resilient. They’re doing well”.

She spoke about whether her daughters ever wanted to see Phillip Garrido again. The answer was unequivocal: no.

“They understand now what he did,” Jaycee said. “They understand that what we lived through wasn’t normal. And they’re building their own lives now, lives he has no part in”.

Today, Jaycee’s daughters are in their thirties and mid-twenties. According to reports from 2024, they’ve chosen to live private lives away from the media spotlight. They’ve attended college, pursued their own interests, and built lives that bear no resemblance to the captivity they were born into.

Where They Are Now

As of 2024, Jaycee Dugard is in her mid-forties.

She continues her work with the JAYC Foundation, though she maintains a relatively low public profile. She’s focused on her family, on healing, on building the life that was stolen from her when she was eleven years old.

Her daughters are thriving—educated, healthy, and strong despite the trauma of their early years. They’ve asked for privacy, and Jaycee has fiercely protected that, understanding that they deserve to define their own identities separate from the circumstances of their birth.

Terry Probyn, now in her seventies, finally got to stop looking at the moon and wondering. Her daughter came home. It took eighteen years, but she came home. In a 2024 interview marking the anniversary of Jaycee’s kidnapping, Terry reflected on those “hellish years” of not knowing.

“I never gave up,” she said simply. “I couldn’t. She was out there, and I knew it. A mother knows”.

Phillip Garrido died in prison on August 28, 2021, at age 70. He never showed remorse for his crimes. Nancy Garrido remains in prison, eligible for parole in 2029. Victim advocates have vowed to appear at any parole hearing to ensure she never walks free.

The Lessons We Must Never Forget

The story of Jaycee Lee Dugard is many things.

It’s a horror story about systemic failure—about parole officers who didn’t look in the backyard, about deputies who didn’t follow up on 911 calls, about a registered sex offender who was able to hide two children in plain sight for nearly two decades.

It’s a testament to the resilience of the human spirit—about a girl who survived unimaginable abuse and raised two daughters with love despite having her own childhood stolen.

It’s a mother’s unwavering devotion—about a woman who looked at the moon every night for 6,575 nights and refused to believe her daughter was dead.

And it’s a reminder that hope—even when it seems foolish, even when statistics say to give up—is sometimes all we have.

After Jaycee was found, reforms were implemented in California’s parole system. Parole officers were required to conduct more thorough home inspections. Background checks were improved. Training was enhanced to help officers recognize signs of hidden victims.

But the question remains: How many other Jaycees are out there, hidden in backyards and basements, invisible to a system that’s supposed to protect them?

Jaycee’s story forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about how easily people can hide in plain sight, how systems designed to protect can fail catastrophically, and how society often looks away from what’s right in front of us.

“If you see something, say something,” law enforcement officials remind us. “And don’t give up if the first person you tell doesn’t listen. Keep pushing. Keep asking questions. You might save a life”.

A Message of Hope

In every interview she’s given, every speech she’s made, Jaycee has emphasized one central message: Don’t give up.

Don’t give up on missing loved ones. Don’t give up on survivors. Don’t give up on the possibility that even in the darkest circumstances, the human spirit can endure.

“I’m not a victim,” Jaycee has said repeatedly. “I’m a survivor. And there’s a difference”.

Terry Probyn echoes this message for other parents of missing children.

“Don’t ever give up,” she says. “Even when everyone tells you it’s hopeless. Even when years pass. Keep looking. Keep hoping. Keep the light on. Because sometimes—not often enough, but sometimes—the impossible happens”.

Jaycee’s case has inspired other families to keep searching, to keep advocating, to refuse to let their missing loved ones be forgotten. Her story has become a beacon of hope for parents who wake up every day to empty bedrooms and unanswered questions.

The Moon Still Shines

On warm summer nights in South Lake Tahoe, if you happen to pass by a certain house on a quiet street, you might see a woman standing outside, looking up at the moon.

But now, she’s not alone.

Sometimes her daughter stands beside her. Sometimes her granddaughters join them. And they look up at that same moon that carried whispered messages for eighteen years, that connected a mother and daughter across 120 miles of California landscape, that became a symbol of hope when hope seemed impossible.

The moon is just the moon, of course. It doesn’t carry messages. It doesn’t grant wishes. It’s just a celestial body reflecting the sun’s light.

But for Terry and Jaycee Dugard, that moon means something more.

It means that love can survive eighteen years of separation. It means that a mother’s devotion can endure 6,575 nights of not knowing. It means that even in the darkest captivity, a girl can look up at the sky and know her mother is looking at the same moon, thinking of her, loving her, waiting for her.

And sometimes—not often enough, but sometimes—that’s enough to bring someone home.

Jaycee Dugard was kidnapped at eleven years old. She spent eighteen years in captivity. She gave birth to two daughters in a backyard compound, raising them with no medical care, no education, no contact with the outside world.

But she survived.

She came home.

And today, she’s not defined by what was done to her, but by what she’s built from the ashes of that stolen life.

She’s a mother. A daughter. An advocate. A survivor.

She’s Jaycee Lee Dugard—a name she couldn’t say for eighteen years, a name that now represents hope for missing children and their families around the world.

The pink-clad eleven-year-old who walked to a bus stop in 1991 is gone. In her place is a woman who looked into the abyss of human cruelty and still found reasons to hope, to love, to build something beautiful.

Terry kept the porch light on for 6,575 nights.

On the 6,576th night, her daughter finally came home.

And the light? It still burns. Not out of desperate hope now, but as a reminder: Never give up. Never stop looking. Never let them be forgotten.

Because sometimes, after eighteen years in darkness, a stolen girl finds her way back to the light.

Sometimes, the moon really does carry messages farther than we ever dreamed.

And sometimes—just sometimes—love is strong enough to bring someone home.