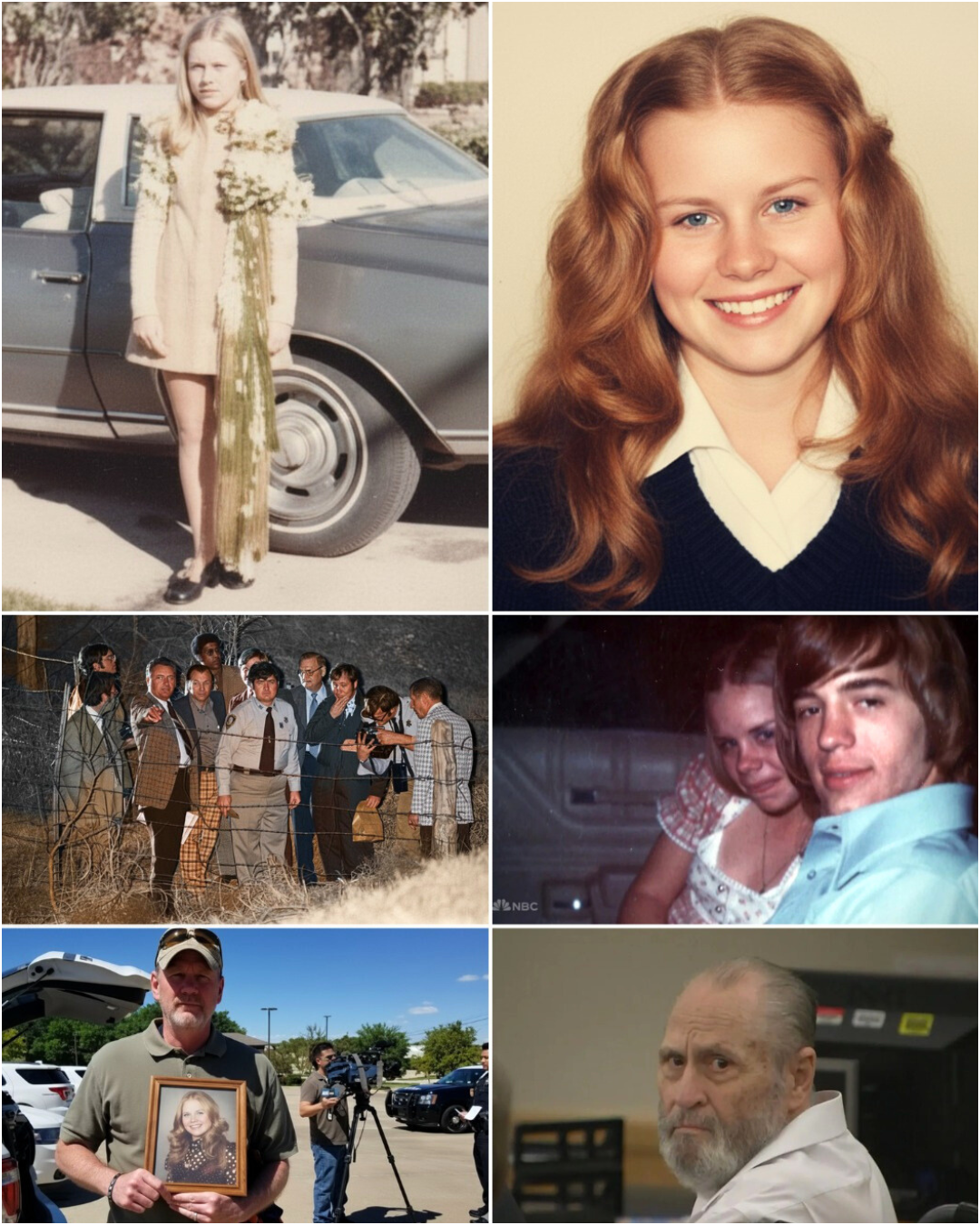

The pink formal dress hung perfectly in the mirror. Seventeen-year-old Carla Jan Walker adjusted it one last time on the evening of February 16, 1974, her dark hair falling in soft waves around her shoulders. Outside, her boyfriend Rodney Roy was pulling into the driveway to pick her up for the Valentine’s Day dance at Western Hills High School in Fort Worth, Texas.

It was supposed to be a magical night. Red and pink streamers hung from the gymnasium ceiling. A DJ spun the latest hits from the radio. Young couples slow-danced to love songs while their classmates laughed and gossiped in clusters around the punch bowl. For Carla—a popular junior with an infectious smile and dreams of becoming a nurse—this was exactly how a Saturday night in 1974 Texas should be.

She had no way of knowing this would be her last dance. That within hours, she’d be ripped from Rodney’s car in a bowling alley parking lot. That she’d spend her final 48 hours in unimaginable terror. That her killer would walk free for 46 years—raising children, becoming a grandfather, sleeping peacefully every night while her family shattered into pieces.

And she couldn’t have imagined that nearly half a century later, science would reach back through time and whisper her killer’s name.

When the Music Stopped

The Valentine’s dance ended around midnight, but Carla and Rodney weren’t ready for the night to be over. Like teenagers everywhere, they wanted just a few more minutes together before the weekend ended and Monday morning classes began. They decided to stop at the Ridglea Bowling Alley on Camp Bowie Boulevard—a popular hangout where kids their age gathered on weekend nights.

Rodney pulled his car into the dimly lit parking lot around 12:30 a.m. Carla sat in the passenger seat, probably still talking about the dance, about their friends, about ordinary teenage things that felt important in that moment. The bowling alley’s neon lights flickered in the darkness. A few other cars dotted the lot. Everything seemed normal.

Neither of them noticed the danger watching from the shadows.

The passenger door exploded open without warning.

A man’s hand shot in and grabbed Carla by the arm, yanking her toward him with brutal force. Before Rodney could process what was happening, he found himself staring down the barrel of a .22 caliber pistol pointed directly at his face.

“I am going to kill you,” the man snarled.

Rodney’s teenage instincts kicked in immediately. This was his girlfriend. He had to protect her. He lunged toward the attacker, reaching for the gun, desperate to fight back. But the gunman was ready. The pistol came down hard—once, twice, three times—pistol-whipping Rodney with savage force across the back of his head and forehead.

Blood poured down Rodney’s face. His vision blurred. Pain exploded through his skull. He heard shots—later investigation would reveal the gun clicked three times against his face but the bullets never fired, perhaps saving his life. But the pistol-whipping was devastating enough.

Through the haze of pain and confusion, Rodney heard Carla scream. He tried to reach for her, tried to get up, tried to do something—anything—to save her. But darkness was closing in fast.

The last thing Rodney heard before losing consciousness was Carla’s voice, desperate and terrified, crying out words that would haunt him for the rest of his life: “Rodney, go get my dad!”

Then she was gone.

When Rodney regained consciousness—he didn’t know if it had been seconds or minutes—the passenger door hung open. Blood covered the interior of the car and soaked his clothes. His head throbbed with agonizing pain. And Carla was nowhere to be seen.

He stumbled out of the car, calling her name into the empty parking lot. Only silence answered. The few other cars in the lot sat dark and still. Nobody had heard anything. Nobody had seen anything. In those pre-cell phone days, there were no cameras, no instant alerts, no way to track where Carla had been taken.

Disoriented and bleeding, Rodney managed to make it to a nearby convenience store where someone called the police. Within minutes, sirens filled the night air.

“This happened so fast,” Rodney would testify 47 years later, his voice still heavy with the weight of that night. “This was so fluid that it’s like to me it was less than two minutes from start to finish and Carla was out of the car.”

The Phone Call Every Parent Fears

Terry Probyn, Carla’s mother, was at home when the call came. The words hit her like a physical blow: There had been an attack. Rodney had been injured. Carla was missing.

Terry raced to the scene, her mind spinning with terrible possibilities. When she arrived at the Ridglea Bowling Alley, police cars surrounded the parking lot. Crime scene investigators photographed Rodney’s blood-spattered car. Paramedics were treating Rodney for his head injuries—deep gashes that would require stitches, wounds that would leave both physical and psychological scars.

Inside the car, investigators found disturbing evidence: blood spatter from the violent assault, signs of a desperate struggle, and a .22 caliber magazine clip that had apparently been dropped by the attacker during the chaos.

Officers documented everything meticulously. They took Rodney’s statement, though the young man was still dazed from the head trauma. They interviewed everyone in the vicinity. They sent out alerts to surrounding jurisdictions. Within hours, a massive search operation was underway.

But there were no solid leads. The attack had happened so quickly, in such confusion and violence, that Rodney could provide only general descriptions. The attacker had appeared out of nowhere, struck with brutal efficiency, and disappeared just as quickly.

Somewhere out there in the darkness of Fort Worth, a predator had seventeen-year-old Carla Walker. And the clock was ticking.

Three Days of Hell

For 72 hours, Carla Walker’s family lived in the special kind of purgatory reserved for those whose loved ones vanish without a trace. Hope and dread waged war in their hearts with every passing hour.

Terry showed Carla’s photograph to everyone in Fort Worth—store clerks, gas station attendants, random strangers on the street. Have you seen my daughter? Have you seen this girl? Her father joined volunteer search parties that combed through fields, vacant lots, and wooded areas around the city. They checked drainage ditches and abandoned buildings. They followed every tip, no matter how unlikely.

Carla’s younger brother Jim, just twelve years old, watched helplessly as his parents unraveled with worry. He was old enough to understand that something terrible had happened, young enough that the trauma would color his entire childhood. The house that had always been filled with laughter and normalcy now echoed with phone calls to police, whispered conversations between his parents, and his mother’s quiet sobs when she thought nobody was listening.

This was 1974—an era before cell phones, before amber alerts, before surveillance cameras on every corner. When someone was taken into the night, finding them required old-fashioned detective work, luck, and prayers. The Fort Worth Police Department did everything they could. They interviewed hundreds of people. They processed every piece of evidence from the crime scene. They worked around the clock.

But leads were scarce. Nobody had seen a car speeding away from the bowling alley. Nobody had witnessed Carla being forced into a vehicle. The few other people in the parking lot that night had been inside the bowling alley or in their cars and hadn’t noticed anything unusual until they heard sirens.

On February 20, 1974—three days after Carla was abducted—a rancher discovered something while checking his property near Benbrook Lake, about nine miles from where Carla had been taken.

It was a body in a culvert.

It was Carla Jan Walker.

The Autopsy That Revealed a Monster

The medical examiner’s report revealed details so disturbing that they would haunt investigators for decades.

Carla had not been killed immediately after her abduction. Instead, she had been held captive for approximately two days—48 hours during which she endured horrors that no seventeen-year-old should ever experience. The autopsy showed evidence of repeated assault. She had been tortured. Toxicology reports indicated she had been injected with morphine, likely to keep her subdued.

The cause of death was strangulation. Someone had wrapped their hands around this teenage girl’s throat and squeezed until her dreams of becoming a nurse, her plans for graduation, her entire future—all of it—went dark.

Medical examiners collected biological evidence from Carla’s body, including DNA samples from her attacker. This evidence was carefully preserved and stored in the police department’s evidence room—standard protocol even in 1974, though the technology to analyze DNA for forensic purposes wouldn’t exist for more than another decade.

The evidence told a story of prolonged suffering. Carla Walker had spent her final hours in the hands of a monster. She had been beaten, violated, drugged, and ultimately murdered. And somewhere, her killer was out there, likely already working to establish an alibi, to blend back into normal society, to pretend he was just an ordinary person.

The funeral was held days later at a Fort Worth church packed with mourning friends, family members, and classmates who couldn’t comprehend how someone so full of life could be gone. Seventeen years old—that’s all Carla got. No high school graduation in 1975. No college. No nursing career. No wedding. No children. No growing old. Just a pink formal dress, one last dance, and then darkness.

“There were really dark times watching the pain my mom went through,” Jim Walker would say 46 years later, his voice still thick with emotion. He was only twelve when his sister was murdered—young enough that the tragedy would define his childhood, but old enough to remember every terrible detail of his family’s anguish.

The Investigation: So Close, Yet So Far

In the days and weeks following Carla’s murder, Fort Worth detectives worked the case with the intensity that such brutal crimes demand. They had physical evidence: the .22 caliber magazine clip found at the abduction scene, biological samples from Carla’s body, and Rodney’s description of the attack. They had a timeline. They had a crime scene. What they needed was a suspect.

The magazine clip became a crucial lead. Firearms experts determined it was designed for a .22 caliber Ruger pistol. In 1974 Fort Worth, that meant potentially thousands of guns—.22 caliber pistols were common, affordable, and widely owned. But it was a starting point.

Detectives began the painstaking work of interviewing people who lived in the area around the bowling alley and near where Carla’s body had been found. They talked to known criminals. They investigated anyone with a history of violence or assault. They ran down every tip that came in from the public.

One name caught their attention: Glen Samuel McCurley.

McCurley lived in Fort Worth, less than two miles from where Carla’s family lived. When detectives knocked on his door to ask routine questions about whether he’d seen or heard anything unusual, they noticed something interesting: McCurley owned a .22 caliber Ruger pistol, and the magazine clip found at the crime scene was consistent with his weapon.

It seemed very promising. Extremely promising, in fact.

Detectives brought McCurley in for questioning. They asked him about his whereabouts on the night of February 16-17. They asked about his gun. They pressed him for details.

But McCurley had an explanation that investigators couldn’t easily disprove: He claimed his .22 caliber pistol had been stolen several weeks before Carla’s abduction. It was a convenient story, and McCurley added a detail that made it seem more plausible—he said he hadn’t reported the theft to police because, as a convicted felon, he wasn’t legally allowed to own a firearm in the first place.

This admission was incriminating in its own way. It meant McCurley was willing to confess to illegal gun possession—a serious crime that could send him back to prison—rather than cooperate fully with the murder investigation. But it also provided him with plausible deniability. If his gun had truly been stolen, then whoever stole it could have been Carla’s killer.

McCurley even agreed to take a polygraph test. He passed.

Without the gun itself, without fingerprints clearly linking McCurley to the magazine clip, without eyewitnesses placing him at the scene, detectives didn’t have enough evidence for an arrest. And critically, DNA analysis didn’t exist yet as a forensic tool. The biological evidence collected from Carla’s body was carefully stored and catalogued, but in 1974, it was essentially useless for identification purposes.

Investigators interviewed McCurley extensively. They documented his story about the stolen gun. They noted his criminal history. They filed him away as a “person of interest” and kept investigating other leads. But eventually, as months turned into years, the case went cold.

There was simply nowhere else to go. Every promising lead had been exhausted. Every tip had been followed up on. The evidence they had wasn’t enough to charge anyone, and no new information was coming in.

The murder of Carla Jan Walker became one of Fort Worth’s most frustrating unsolved cases—a brutal crime with evidence, with suspects, with theories, but no arrests. No justice. Just a grieving family and a community that knew a killer walked among them but couldn’t prove who it was.

A Killer Hiding in Plain Sight

Meanwhile, Glen Samuel McCurley went on with his life.

If he was indeed Carla’s killer—and decades later, science would prove beyond any doubt that he was—then he carried a terrible secret for the next 46 years. He got married. He had children who grew into adults. He became a father and grandfather. He went to work, came home, attended church, lived in the same general Fort Worth area where Carla had been murdered.

For all outward appearances, he was just another resident living an ordinary life. His neighbors probably thought he was a regular guy. His family loved him. He attended community events. He seemed normal.

But if McCurley was the killer, then he woke up every single morning for 46 years knowing what he’d done. He saw news stories about Carla’s case on its anniversaries. He knew her family was still searching for answers. He knew that somewhere in a police evidence room, biological samples with his DNA were carefully stored in boxes and file cabinets.

And he said nothing. Did nothing. Just kept living his life while Carla Walker remained seventeen forever, buried in a cemetery with an unsolved murder hanging over her grave like a dark cloud.

That’s 46 years of sleeping next to his wife while knowing he’d kidnapped, assaulted, and murdered a teenage girl. 46 years of hugging his children and grandchildren while knowing he’d strangled someone else’s daughter. 46 years of attending church services and community gatherings while carrying the knowledge of his horrific crime.

How does someone do that? How does someone compartmentalize that level of evil and just… live normally?

Psychologists call it compartmentalization—the ability to separate different aspects of one’s life into distinct mental boxes so they don’t have to confront the contradictions. For McCurley, if he was indeed the killer, this meant living a “normal” life in one box while keeping his monstrous crime locked away in another box he rarely opened.

Jim Walker grew up in the shadow of his sister’s unsolved murder. He watched his mother age under the weight of unanswered questions. He saw the case grow colder with each passing year. Birthdays came and went. His sister would have turned 20, then 30, then 40. But she remained frozen at seventeen in the family’s memories and in the police files.

“There were really dark times,” Jim would later recall, his voice breaking even decades after the fact.

The family tried to move forward, but how do you move forward when the person responsible for destroying your world is still out there somewhere, living freely? How do you find peace when justice has been denied?

Terry Probyn, Carla’s mother, refused to give up hope that someday, somehow, her daughter’s killer would be identified. She kept in touch with the Fort Worth Police Department’s cold case unit. Every few years, she’d call to ask if there were any new developments. The answer was always the same: No, ma’am. We’re sorry. The case is still unsolved.

But she never stopped hoping. And unknown to her, scientific advances were slowly catching up to the evidence that had been waiting patiently in storage for decades.

When Science Refused to Let Evil Hide

In 2019—45 years after Carla’s murder—something unexpected happened that would set in motion a chain of events leading to justice.

An anonymous letter arrived at the Fort Worth Police Department. The letter appeared to have been written shortly after Carla’s murder in 1974, though someone had held onto it for more than four decades before finally sending it to authorities. The contents were cryptic and disturbing: “- Blank- Carla – is hard say but is true.”

What did it mean? Who had written it? Why had someone kept this letter for 45 years before sending it? These questions sparked renewed interest in the case. Local media picked up the story, and once again, Carla Walker’s name was in the Fort Worth news.

The publicity from the mysterious letter did something crucial: it reminded people that this case was still unsolved, still open, and still desperately in need of resolution. It put pressure on the Fort Worth Police Department to take another look with fresh eyes and modern technology.

And it caught the attention of someone who specialized in exactly this kind of cold case: Paul Holes.

Paul Holes was already a legend in the cold case investigation community by 2020. He was the investigator who had been instrumental in identifying the Golden State Killer—one of California’s most notorious serial offenders who had evaded capture for decades until genealogical DNA finally revealed his identity in 2018. After retiring from law enforcement, Holes had become the host of “The DNA of Murder,” a show on the Oxygen network that examined unsolved cases and applied modern forensic techniques to see if they could finally be solved.

In April 2020, the Oxygen network aired an episode of Holes’ show focused on Carla Walker’s murder. Holes reviewed the case file, examined the evidence that had been stored for 46 years, and discussed with Fort Worth detectives the possibilities that modern DNA analysis might offer.

The episode brought national attention to a case that had been mostly local knowledge for decades. But the show did something even more important than raise awareness: Paul Holes used his connections and expertise to introduce Fort Worth Police Department Cold Case Detectives Leah Wagner and Jeff Bennett to a cutting-edge forensic genetics company called Othram Inc.

Othram specialized in a revolutionary type of DNA analysis that could work with degraded, contaminated, or minimal DNA samples—exactly the kind of evidence that often exists in cold cases. Traditional DNA testing requires relatively pristine samples with sufficient genetic material. But evidence from 1974 had been stored for nearly half a century. Despite careful preservation, it had been exposed to temperature changes, natural degradation, and the simple passage of time. Standard DNA analysis had been attempted on Carla’s case before with limited success—the samples were too old, too degraded, or too contaminated to process with conventional methods.

But Othram was different. The company used advanced techniques including forensic-grade genome sequencing that could extract readable DNA profiles from samples that other labs had deemed unusable. Even more significantly, Othram specialized in genealogical DNA analysis—the same technique that had helped catch the Golden State Killer.

Instead of trying to match DNA directly to someone in a criminal database like CODIS (the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System), genealogical DNA analysis works differently. Investigators upload the DNA profile to public genealogical databases where millions of people have voluntarily submitted their genetic information to learn about their ancestry. The system then searches for relatives of the perpetrator—maybe a second cousin, or a great-uncle, or some distant relation.

From there, investigators build out family trees using traditional genealogy research, narrowing down the pool of potential suspects based on age, location, and other factors. Eventually, they can identify a specific individual as a likely match, at which point they obtain a warrant for that person’s DNA to confirm.

The Oxygen network, recognizing the potential breakthrough and wanting to see the case solved, agreed to pay for Othram’s expensive testing of the evidence from Carla Walker’s case. This was crucial—advanced DNA analysis can cost tens of thousands of dollars, and many cold cases lack the budget for such cutting-edge forensic work.

Detectives Wagner and Bennett carefully packaged the biological evidence that had been collected from Carla’s body in 1974 and sent it to Othram’s laboratory. Then came the waiting. DNA analysis of degraded samples isn’t quick—it requires meticulous work, specialized equipment, and extraordinary expertise.

But within weeks—not months or years, but weeks—Othram delivered results that would change everything.

The DNA Doesn’t Lie

The DNA profile extracted from evidence collected from Carla Walker’s body in 1974 was clear enough for analysis. Othram’s advanced sequencing technology had successfully pulled readable genetic data from samples that were 46 years old—samples that conventional DNA testing methods had been unable to process with sufficient accuracy.

Now came the detective work. Using genealogical databases and family tree construction, investigators began to narrow down potential matches. They looked for male individuals in the Fort Worth area whose age would have been appropriate for the crime in 1974—someone who would have been in their late twenties to mid-thirties at the time. They cross-referenced with old case files, including that list of “persons of interest” who had been interviewed decades earlier.

And one name kept appearing in the genealogical analysis: Glen Samuel McCurley.

Now 77 years old, McCurley was the same man who had been questioned extensively in 1974. The same man who owned a .22 caliber Ruger pistol that matched the magazine clip found at the crime scene. The same man who had claimed his gun was stolen. The same man who had passed a polygraph test. The same man who, despite being a strong suspect, had never been charged.

For 46 years, he had lived freely. He had aged from a 31-year-old man into a senior citizen. He had probably convinced himself that he was safe, that too much time had passed, that the evidence was too old, that no one would ever be able to prove anything.

He was catastrophically wrong.

Armed with Othram’s DNA analysis suggesting McCurley as a strong suspect through genealogical matching, Fort Worth detectives applied for a warrant to collect a DNA sample directly from him for comparison. In September 2020, officers approached McCurley and obtained the sample.

Then it was sent to the lab for definitive testing.

The results came back: it was a match. The DNA from Carla Walker’s body matched Glen Samuel McCurley’s DNA profile. Not partially. Not probably. Definitively. With the kind of scientific certainty that leaves no room for doubt.

On Monday, September 21, 2020—exactly 46 years, 7 months, and 4 days after he abducted Carla Walker from a bowling alley parking lot—Fort Worth Police arrested 77-year-old Glen Samuel McCurley and charged him with capital murder.

“Finally, Finally”

The press conference announcing McCurley’s arrest was emotional. Fort Worth Police Department officials stood at podiums and explained how modern DNA technology had finally solved one of their oldest and most painful cold cases. They thanked Othram, Paul Holes, the Oxygen network, and most importantly, the detectives who had never given up on Carla.

But the most powerful moment came when Carla’s brother Jim Walker—now 58 years old, older than his sister would ever be—spoke to the media.

He struggled to maintain composure as he addressed the cameras, his voice breaking with emotion that had been building for nearly half a century.

“The word that came across my brain was finally, finally,” Jim said. “This is a resolution that’s been prayed for.”

He talked about being just twelve years old when Carla was murdered. About growing up watching his mother suffer through “really dark times.” About how the unsolved nature of the crime had left a wound in his family that never fully healed, that never stopped hurting, that colored every birthday, every holiday, every family gathering for 46 years.

And now, after nearly half a century, there would finally be answers. Finally be accountability. Finally be justice.

The arrest made national news. It was another stunning example of how DNA technology was revolutionizing cold case investigations. Cases that had seemed permanently unsolved—cases where the suspects had died or the evidence had degraded or too much time had passed—were suddenly being cracked open. Killers who thought they’d gotten away with murder were being confronted with scientific evidence that couldn’t be argued away or explained with convenient lies about stolen guns.

Glen Samuel McCurley was booked into the Tarrant County Jail on charges of capital murder. Prosecutors initially considered seeking the death penalty, but ultimately decided against it given McCurley’s advanced age and the decades that had passed. Instead, they would seek life in prison without the possibility of parole.

McCurley entered a plea of not guilty. Despite the DNA evidence, despite being the prime suspect from 1974, despite all of it, he maintained his innocence. His lawyers prepared for trial.

The case was set for August 2021—almost exactly one year after his arrest.

In the Courtroom: Confronting the Monster

The trial of Glen Samuel McCurley began in August 2021 in Tarrant County, Texas. Media packed the courtroom. Carla Walker’s family sat in the front rows—her siblings, now in their 50s and 60s, finally getting to face the man accused of murdering their sister nearly half a century ago.

Prosecutors methodically laid out their case. They presented the evidence from 1974: the abduction from the bowling alley, Rodney Roy’s testimony about the attack, the magazine clip that matched McCurley’s gun, the autopsy findings showing Carla had been held for days and subjected to horrific abuse before being strangled to death.

They explained how McCurley had been interviewed back then and how his story about the stolen gun had prevented his arrest at the time. They detailed how he had lived just two miles from Carla’s home, how he fit the profile, how everything pointed to him—but without DNA technology, they simply couldn’t prove it in 1974.

Then they brought in the modern evidence: Othram’s DNA analysis, the genealogical matching, the direct DNA sample that definitively placed McCurley’s genetic material on Carla’s body from the assault. The scientific testimony was damning and irrefutable.

One of the most emotional moments came when Rodney Roy took the stand. Now in his mid-60s, Rodney had carried the weight of that night for his entire adult life. He had survived the attack that killed his girlfriend. He had been pistol-whipped and shot at. He had lost consciousness and woken to find Carla gone. And he had spent 47 years wondering if there was something more he could have done, some way he could have saved her.

“This happened so fast,” Rodney testified, his voice steady but heavy with decades of pain. “This was so fluid that it’s like to me it was less than two minutes from start to finish and Carla was out of the car.”

The court saw photos of Rodney’s injuries from that night—the deep gashes on his head, the blood covering his face and hair, the wounds that could easily have killed him if the gun had fired properly. The jury heard how he’d tried to fight back despite being at gunpoint and outmatched by an older, stronger attacker. How he’d been beaten unconscious while a predator dragged his girlfriend into the darkness.

The prosecution showed medical evidence from Carla’s autopsy. They detailed—as delicately as possible, given the victim’s family was sitting just feet away—what had been done to her during the two days she was held captive. The morphine injections. The repeated assaults. The strangulation that ended her life.

And through it all, Glen Samuel McCurley sat at the defense table, now 78 years old, his expression largely unreadable. What was going through his mind as he listened to the details of what he’d done? Did he feel remorse? Fear? Or had he lived with his crime for so long that he’d become numb to the horror of it?

Then, on August 23, 2021, something unexpected happened.

McCurley had a “sudden change of heart,” as the media would later describe it. In the middle of the trial, after hearing the evidence against him, after seeing Carla’s family in the courtroom, after 46 years of freedom—he changed his plea from not guilty to guilty.

The courtroom erupted with emotion. Nearly 50 years of waiting for this moment—for this acknowledgment, for this accountability, for these words—came crashing down on Carla Walker’s family all at once.

The Confrontation

When Glen Samuel McCurley stood before the judge and admitted his guilt, it was a moment of profound significance. For the first time in 46 years, he was publicly acknowledging what he’d done. No more lies about stolen guns. No more hiding behind legal technicalities. Just the truth: he had murdered Carla Jan Walker.

But what happened next was even more extraordinary.

Carla’s sister Cindy Walker was given the opportunity to address McCurley directly in court—to stand face-to-face with the man who had destroyed her family and tell him exactly how she felt. She walked up to him, this man who had stolen her sister, who had destroyed her childhood, who had caused her mother decades of suffering, who had lived freely while Carla remained seventeen forever.

Her voice shook with nearly 50 years of accumulated pain, anger, and grief.

“I wish you had done this a long time ago,” Cindy said to McCurley.

Then she asked him the question that families of victims always want answered, the question that keeps them awake at night wondering: “I want to know if you’ve done this to anybody else. You need to bring that out because those families need to know too.”

It was a moment of raw, unfiltered emotion and desperate need for truth. Had there been other victims? Other Carlas whose cases never got solved? Other families still wondering what happened to their daughters?

Investigators had long suspected McCurley might be connected to other unsolved murders of young women in the Fort Worth area during the 1970s and 1980s. The DNA database would eventually reveal if he’d attacked anyone else. But Cindy wanted him to confess, to give other families the closure hers was finally receiving.

McCurley offered no response to her question. He stood silently, providing no answers, no explanations, no apologies beyond the guilty plea itself.

In a moment that surprised everyone in the courtroom, members of McCurley’s own family—who had presumably known him as a grandfather, a father, a husband, just an ordinary man—embraced members of Carla Walker’s family. It was a powerful and heartbreaking acknowledgment that McCurley’s crimes had created victims on both sides. His family had to grapple with the horrifying realization that someone they loved was capable of such monstrous evil.

The judge sentenced Glen Samuel McCurley to life in prison without the possibility of parole. At 78 years old, it was effectively a death sentence. McCurley would spend whatever time he had left behind bars, his freedom finally taken away just as he had taken Carla’s life away all those years ago.

For Jim Walker, Cindy Walker, and the rest of Carla’s family, it was a moment they had prayed for but never been certain would come.

“Finally, finally,” Jim had said when McCurley was arrested. Now, with the guilty plea and life sentence, that “finally” had teeth. There was justice. Not perfect justice—nothing could bring Carla back, nothing could undo 46 years of grief and unanswered questions—but justice nonetheless.

The End of Evil

Glen Samuel McCurley died in prison on July 15, 2023, while serving his life sentence. He was 80 years old. He had spent less than two years behind bars for a crime he’d gotten away with for 46 years.

Some might say he escaped full justice by dying relatively quickly after his conviction. He didn’t spend decades in prison the way many believed he deserved. He didn’t grow old and frail behind bars while contemplating what he’d done. Two years is nothing compared to the lifetime of grief he inflicted on Carla Walker’s family.

But others would argue he got exactly what he deserved: exposure, shame, conviction, and the knowledge that everyone—his family, his community, the entire world—finally knew what he really was. Not an ordinary grandfather. Not a churchgoer. Not a regular Fort Worth resident. But a predator who had kidnapped, tortured, assaulted, and murdered a seventeen-year-old girl, then hid behind a facade of normalcy for nearly half a century.

His death brought the Carla Walker case to its final close. There would be no appeals, no retrials, no legal maneuvering. McCurley was gone, and with him went any hope of learning about other potential victims or understanding what drove him to commit such evil.

Carla’s family could finally, truly move forward knowing that her killer had been caught, convicted, and was now gone. The question mark that had hung over Carla’s grave for 46 years was finally erased.

What This Case Teaches Us

The resolution of Carla Walker’s case offers several profound lessons about crime, justice, and the intersection of old evidence with new technology.

First, it reminds us that evil often looks ordinary. Glen Samuel McCurley wasn’t a monster in appearance. He was someone’s husband, someone’s father, someone’s grandfather. He lived in the community, went to work, attended church, probably seemed perfectly normal to his neighbors. This is perhaps the most unsettling aspect of his case—the reminder that people capable of horrific violence can hide behind facades of normalcy for decades. The person sitting next to you at a restaurant, or serving you at a store, or living down the street could be harboring terrible secrets. Evil doesn’t always announce itself with obvious warning signs.

Second, it shows that families of victims never truly move on without resolution. Jim Walker’s testimony about watching his mother suffer through “really dark times” for decades illustrates the ongoing trauma of unsolved murders. It’s not just the initial grief—it’s the perpetual wondering, the feeling that justice has been denied, the knowledge that somewhere the person responsible is living freely. Resolution doesn’t erase the pain, but it does provide a form of closure that allows families to process their grief differently.

Third, the case demonstrates that technology changes everything. Evidence collected in 1974 by investigators who had no idea DNA analysis would ever exist became the key to solving Carla’s murder in 2020. This has profound implications: it means that how we collect and preserve evidence now will matter for decades to come. It also means that cold cases should never be considered truly closed—they’re just waiting for technology to catch up.

Fourth, it proves that persistence matters. The Walker family never stopped advocating for Carla’s case. The Fort Worth Police Department kept the evidence carefully stored for 46 years. Cold case detectives continued to review the file whenever new technology became available. That persistence—that refusal to give up—ultimately led to justice.

And finally, it sends a powerful message to anyone who has committed a violent crime and thinks they’ve gotten away with it: DNA doesn’t forget. Science only gets better at finding you. The passage of time is no longer protection. What couldn’t be proven in 1974 can absolutely be proven in 2024. The forensic tools available today are extraordinary, and they’re improving every year.

There are an estimated 250,000 unsolved murder cases in the United States. Many of them have DNA evidence that was collected and stored but never successfully analyzed because the samples were too degraded or the technology didn’t exist. Companies like Othram are changing that equation, applying advanced sequencing techniques to cold cases that were thought to be permanently unsolved.

For families like the Walkers, this represents hope—the hope that no matter how much time has passed, justice might still be possible.

Carla Jan Walker was seventeen years old when she went to a Valentine’s Day dance and never came home. For 46 years, that was where her story ended—with darkness, with questions, with injustice.

But then science whispered Glen Samuel McCurley’s name, and Carla’s story got a different ending. Not a happy one—there are no happy endings when a seventeen-year-old is murdered and a family spends half a century grieving.

But a just one.

Finally, finally.