The snow fell soft that Christmas Eve in 1945, blanketing the hills of Fayetteville, West Virginia, in white silence. Inside the two-story timber frame house two miles north of town, laughter bounced off wooden walls as children tore through wrapping paper, their squeals of delight piercing the winter night. Marion, nineteen and working at the local dime store, had surprised her younger sisters—Martha, Jennie, and Betty—with toys she’d saved up to buy. The girls begged their mother to let them stay up late, their eyes shining with the kind of joy that makes parents forget the rules.

Jennie Sodder, her dark hair pulled back from her face, smiled at her husband George across the room. They had built something here, hadn’t they? Ten children between 1923 and 1943, a successful trucking business, respect in their community. George had come to America as a thirteen-year-old boy from Sardinia, Italy, alone after his older brother turned back at Ellis Island. He never spoke much about why he left, but whatever ghosts chased him across the ocean, he’d outrun them. Or so he thought.

That night, Jennie finally gave in to the children’s pleas and let them stay awake a little longer. Around midnight, most of the family drifted to bed, exhausted from celebration. But something felt wrong from the start.

The Night Everything Changed

Jennie woke to the sound of something rolling across the roof. A thud, then a rolling noise, like a ball or something heavier bouncing against the shingles above her head. She opened her eyes in the darkness, listening. The house settled back into silence. She told herself it was nothing—maybe an animal, maybe the wind playing tricks. She pulled the blankets tighter and tried to fall back asleep.

An hour later, she woke again. This time, smoke poured through the doorway, thick and black and choking.

“George!” Her scream cut through the night. “Fire! The house is on fire!”

George bolted upright, his mind struggling to catch up with what his eyes were seeing. Flames crawled up the walls, already devouring the staircase that led to the second floor where five of their children slept: Maurice, fourteen; Martha, twelve; Louis, nine; Jennie, eight; and Betty, five. The heat pushed against them like a living thing.

They ran through the house, grabbing whoever they could reach. Marion, George Jr., John, and little Sylvia made it out, coughing and crying in the snow outside. But the five upstairs—there was no way to reach them. The stairs had become a wall of fire.

George ran to get a ladder he kept leaning against the house. It was gone. He always kept it there, always in the same spot. Tonight, of all nights, it had vanished.

His trucks—he could drive one underneath the window, climb up, break through. He sprinted to where he’d parked them, his heart hammering against his ribs. He turned the key. Nothing. The other truck—same thing. Both dead, though they’d been running fine just hours before.

Jennie was screaming now, her voice raw and breaking, calling out the names of her babies trapped inside. George ran to his neighbor’s house to call the fire department. The line was dead. Another neighbor tried—same result. By the time someone reached the fire chief, precious minutes had bled away.

The Fayetteville Fire Department didn’t arrive for hours. When they finally came, they found George and Jennie standing in the snow, watching their home collapse into ash and ember, their surviving children huddled around them in shock. The firefighters would later explain the delay: so many young men had died in the war, just ended three months prior, and the volunteer force didn’t have enough equipment or manpower.

By dawn on Christmas morning, the house was gone. Just a smoking crater remained, a black scar against the white landscape. And somewhere in that ruin, five children should have been.

But when George and Jennie searched the ashes, they found nothing. No bones. No teeth. No remains at all.

Questions Without Answers

Chief F.J. Morris stood in the rubble and told the Sodders what he believed: the fire had been so hot, so intense, that it cremated the children completely. Their bodies had simply burned away to nothing.

Jennie stared at him, her face hollow with grief and something else—disbelief. She’d spoken to a crematorium worker in town. He told her that even when a body is burned at 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit for two hours, bones remain. Large fragments, pieces that can’t be destroyed by heat alone. The Sodder house had burned for forty-five minutes and collapsed.

How could five children vanish so completely in less than an hour?

The police inspector declared the cause to be faulty wiring. George challenged this immediately. He’d never had problems with the electricity before. Just weeks earlier, the power company had inspected the house and found everything in working order. And what about the ladders? What about his trucks that wouldn’t start?

The coroner’s inquest on December 26 sided with the inspector. Faulty wiring. Accidental fire. Case closed. Death certificates were issued for Maurice, Martha, Louis, Jennie, and Betty Sodder on December 30, 1945.

But George Sodder wasn’t ready to accept that his children were dead. Neither was his wife.

Four days after the fire, George hired a bulldozer and buried the basement under five feet of dirt. He told people he wanted to create a memorial, to plant flowers where his children had died. But the truth was more complicated. He couldn’t bear to look at it anymore. And part of him—a part that grew stronger with each passing day—didn’t believe his children were in that ground at all.

The Threads That Didn’t Add Up

As the shock began to fade and grief hardened into something sharper, George and Jennie started piecing together the strange events that had preceded the fire. Individually, they seemed like odd coincidences. Together, they formed a pattern that chilled them both.

In October, two months before the fire, an insurance salesman had come to their door. George had turned him away—they already had insurance, didn’t need more. The man’s face had darkened. He looked at the house, then back at George. “Your house is going up in smoke one of these days,” he’d said. Then he’d pointed to the wiring. “And your children are going to be destroyed. You are going to be paid for the dirty remarks you have been making about Mussolini”.

George had been vocally opposed to the Italian dictator, and it had caused friction within Fayetteville’s tight-knit Italian immigrant community. Some saw his criticism as betrayal, as turning his back on the old country. But George hadn’t thought much about the insurance man’s threat at the time. People said things when they were angry.

Now, standing in the ruins of his home, those words echoed differently.

A few days before Christmas, a stranger had stopped by asking for directions. Nothing unusual about that. Except the man had lingered, staring at the house, watching the children play in the yard. He’d pointed at the two middle boys and said something under his breath before driving away.

And then there was the night of the fire itself. That noise on the roof that woke Jennie—what was it? Years later, people would speculate it might have been an incendiary device, something thrown to start the blaze. The missing ladder. The trucks that wouldn’t start, though they’d been fine hours before. The cut phone line.

One thing after another, each detail engineered to prevent rescue, to buy time while the fire consumed everything.

George hired a private investigator. What the investigator found made the mystery deeper.

The fire chief’s report stated that the fire had started on the roof or in the attic. But electrical wiring ran through the walls, not the roof. How could faulty wiring cause a fire to start from above?

Several witnesses came forward with stories they’d been afraid to tell. A bus driver reported seeing balls of fire being thrown at the Sodder house that night. A woman who’d been driving past around 1 a.m. said she saw the children looking out from an upstairs window after the fire had started. Another woman claimed she’d driven by around the same time and noticed the lights were still on in the house—odd, if the fire had already destroyed the electrical system.

But the most disturbing testimony came from a man who worked at a nearby crematorium. He told Jennie that he’d been approached by the local fire chief shortly after the blaze. The chief showed him what he claimed was a human heart, found in the debris of the Sodder home. He asked if the man would bury it for him in a special box.

The crematorium worker agreed, but something about the “heart” bothered him. So he took it to a pathologist for examination. The pathologist’s conclusion: it was beef liver, probably from a cow, and it had never been subjected to fire. Someone had planted it.

Why would the fire chief fabricate evidence? Unless he was trying to convince the Sodders their children were really dead, to stop them from asking questions, from searching.

A Mother’s Unshakable Faith

Jennie Sodder refused to mourn. She kept the children’s rooms exactly as they’d left them, their clothes hanging in closets, their toys gathering dust on shelves. She waited.

George threw himself into the investigation. He tracked down every lead, every whisper, every half-formed rumor. Someone had seen children matching the description of the Sodder kids getting into a car on the morning after the fire. Another person claimed to have spotted them at a hotel in Charleston, South Carolina. Each thread led nowhere, but George pulled at them anyway.

In 1949, four years after the fire, the Sodders decided to excavate the site. They wanted to search the ashes one more time, to find any evidence that might have been missed. They brought in experts.

The excavation turned up small bone fragments. Finally, proof. Except when the bones were analyzed, they belonged to someone at least sixteen years old. Betty had been five. Louis had been nine. The youngest child who’d disappeared was eight. And the bones showed no signs of having been burned.

The pathologist concluded the fragments had likely come from the dirt George used to fill in the basement—dirt he’d bought from another site. Someone else’s remains, deposited there by accident or by design.

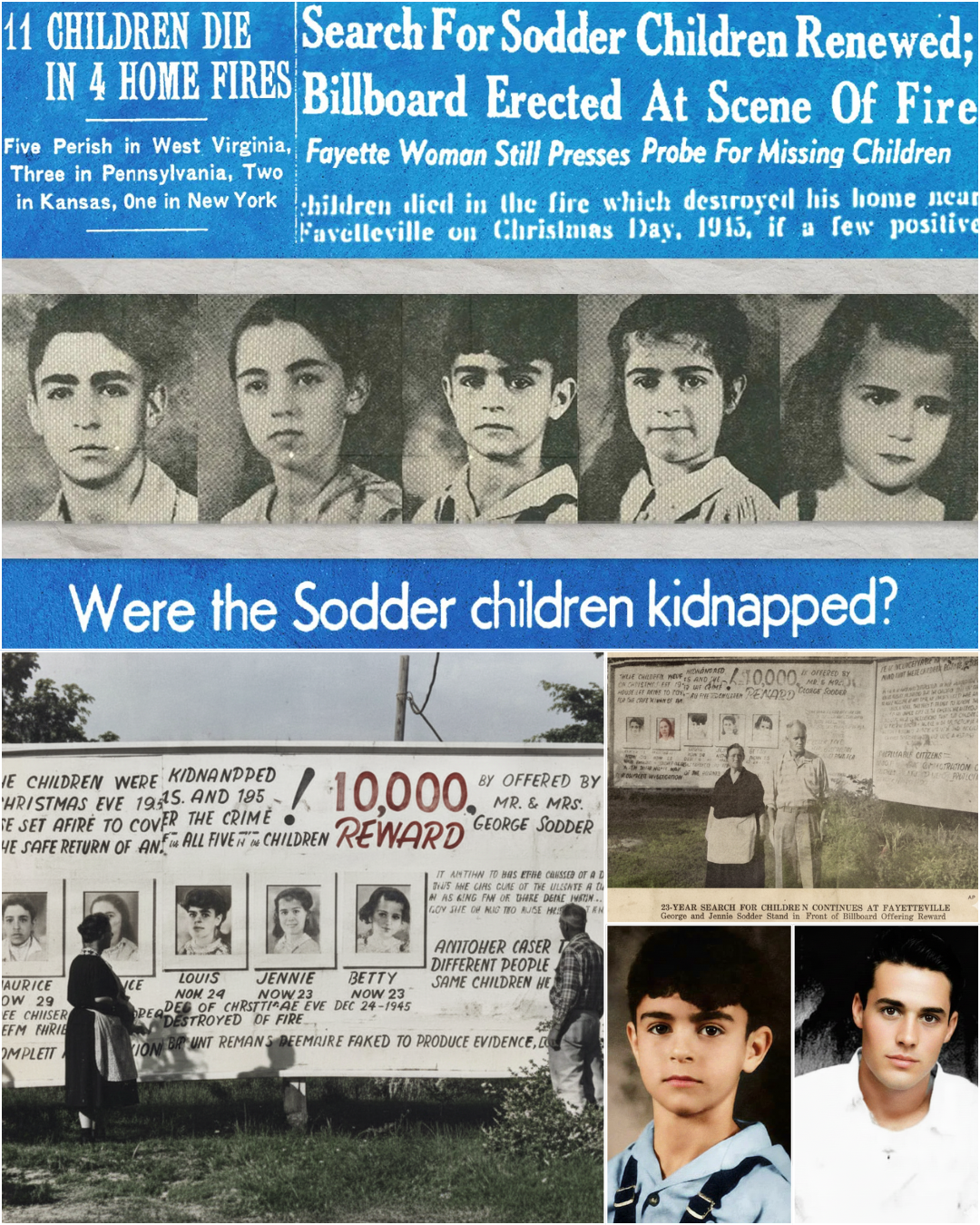

The Sodders built a new house on the same property, directly over where the old one had stood. They erected a billboard along Route 16, the main highway through town. The sign displayed enlarged photographs of the five missing children, asking anyone with information to come forward. The billboard stayed up for decades, a constant reminder to everyone who drove past that the Sodders were still searching, still believing.

George spent thousands of dollars on private investigators over the years. One detective claimed to have found the children living in a small town, but when George rushed to the location, no one was there. Another investigator took his money and vanished. The disappointments piled up, but George never stopped.

Jennie wrote letters to the FBI, to police departments across the country, to anyone who might listen. Most went unanswered. Those that did respond offered sympathy but no help. This was a local matter, they said. Not federal jurisdiction.

The community of Fayetteville split into camps. Some believed the fire had killed the children, that the Sodders were trapped in denial, unable to accept the horrific truth. Others whispered about kidnapping, about organized crime, about secrets buried deeper than the ashes. Every Christmas, the debate reignited. People went over the evidence again, choosing sides, arguing theories.

But for George and Jennie, it wasn’t a debate. It was their life, bleeding out one day at a time.

A Letter From Kentucky

Twenty-three years passed. Twenty-three Christmases came and went, each one a fresh wound that never quite healed. George’s hair turned white. The lines deepened around Jennie’s eyes. Their surviving children grew up, married, had kids of their own. But the five who vanished remained frozen in time—Maurice at fourteen, Martha at twelve, Louis at nine, Jennie at eight, Betty at five.

Then, in 1968, something happened that reignited everything.

Jennie walked to the mailbox on an ordinary afternoon and found an envelope addressed only to her. No return address. The postmark read Kentucky. Her hands trembled as she tore it open.

Inside was a photograph of a young man, probably in his mid-twenties. Dark hair, strong jaw, eyes that seemed familiar in a way that made her chest tighten. She flipped the photo over. On the back, someone had scrawled a message in cramped handwriting: “Louis Sodder. I love brother Frankie. Ilil Boys. A90132”. Or maybe it said A90135—the numbers were hard to read.

Jennie stared at the photograph until the image blurred. Louis would have been thirty-two years old in 1968. This man looked about the right age. The resemblance to her lost son was undeniable. But could it really be him?

She showed George. He studied the photo in silence, his jaw working, emotions flickering across his face too fast to name. Hope hurt worse than grief sometimes. Hope was dangerous.

“Brother Frankie”—that had to be their son Frank, one of the survivors. But what did “Ilil Boys” mean? And those numbers at the end—were they a code? An address? A case number? The Sodders spent days trying to decode the message, arranging and rearranging the letters and numbers, searching for hidden meaning.

They couldn’t publish the photo, couldn’t ask the public for help. What if doing so put Louis in danger? What if whoever had taken the children was watching, waiting? So they kept it private, shared it only with close family and trusted investigators.

George hired another private detective and sent him to Kentucky to follow the lead. They gave him money, gave him every detail they had. Days turned into weeks. They heard nothing. The detective vanished completely, took their money and disappeared into silence.

Still, they amended the billboard on Route 16, replacing Louis’s childhood photo with this new image of what he might look like as an adult. They hung an enlarged version over their fireplace. Jennie looked at it every day.

“Time is running out for us,” George told a reporter who came to interview them that year. His voice carried the weight of two decades of searching, of hope deferred and leads gone cold. “But we only want to know. If they did die in the fire, we want to be convinced. Otherwise, we want to know what happened to them”.

A year later, in 1969, George Sodder died. He never got his answer.

Theories That Haunted a Family

Over the years, the surviving Sodder children—along with their own kids and grandkids—developed theories about what really happened that Christmas Eve. They talked to old-timers in Fayetteville who remembered things, who’d heard whispers, who knew more than they’d ever told police.

The most persistent theory involved the Sicilian Mafia.

George Sodder had been approached multiple times over the years by men claiming to represent certain “interests”. They wanted him to work with them, to use his trucking business for their purposes. George refused every time. He was a proud man, built his business from nothing, and he wasn’t about to hand it over to criminals.

There had been attempts to extort money from him too. Pay up, or face consequences. George called their bluff. He believed this was America, not the old country. Here, you could stand up to bullies. Here, the law meant something.

And then there were his political views. George despised Mussolini, spoke openly against the dictator and against fascism. In the Italian immigrant community of Fayetteville, this made him enemies. Some saw him as a traitor, as someone who’d turned his back on Italy when it needed solidarity.

What if the fire wasn’t meant to kill the children at all? What if someone burst through the unlocked front door that night, told the five kids the house was burning and they needed to leave immediately, promised to take them somewhere safe? Children would trust an adult they recognized from the community. They would go.

Maybe whoever took them intended to use them as leverage against George—a way to force his cooperation or extract money. Maybe the plan went wrong. Maybe the children were killed that night, or maybe they were taken far away, hidden where George could never find them.

Some family members believed the children might have been taken back to Italy. Shipped overseas, given new names, raised by strangers who told them their real parents were dead. It would explain why they never came home, even as adults. If they believed George and Jennie had died in the fire, if they’d been told lies and raised in a world where seeking the truth was dangerous, they might never have tried to find their way back.

But there was another theory, darker and simpler. Maybe the fire was exactly what it appeared to be—arson, committed by someone with a grudge. Maybe the children died that night after all, their bodies destroyed in ways the family couldn’t accept. The Mafia connection, the strange photograph, the cryptic messages—maybe those were just cruel hoaxes, ways to torment grieving parents, to keep hope alive when it should have been buried.

George and Jennie’s granddaughter, also named Jennie Henthorn, grew up hearing the stories. She watched her grandfather chase leads until his body gave out. “Right before my grandfather died, my dad took him to Texas to follow up on a lead,” she told a reporter decades later. “He was very sick, and my dad drove him the whole way to Texas—and he was so disappointed that it didn’t pan out that they literally turned around and drove back”.

That was George’s life in the end—driving across the country on tips that led nowhere, arriving too late or at the wrong place, always one step behind answers that slipped through his fingers like smoke.

The Community That Couldn’t Forget

In Fayetteville, the Sodder case became something more than a tragedy. It became an obsession, a ghost story told and retold, a mystery that defined the town in ways both troubling and profound.

Every Christmas, people drove past the billboard on Route 16 and felt the weight of those five faces staring out, asking wordlessly what happened, demanding to be remembered. Parents held their children a little tighter. Doors that used to stay unlocked at night got bolted shut. The fire changed how people thought about safety, about trust, about what horrors could unfold in small-town America.

Some townspeople believed the Sodders, thought there was truth to the kidnapping theory. Others rolled their eyes, considered George and Jennie delusional, unable to accept that their children had burned to death. Arguments broke out at diners and church socials. Families stopped speaking to each other over disagreements about what really happened.

The case attracted investigators, journalists, true crime enthusiasts from all over the country. They came with cameras and notebooks, asked questions, dug through old records, interviewed anyone who’d been alive in 1945. Some stayed for weeks. Some wrote books and articles that kept the story circulating. But none of them solved it.

In 1950, the state of West Virginia officially declared the case closed. Governor Okey L. Patterson and State Police Superintendent W.E. Burchett met with the Sodders and told them their search was “hopeless”. They needed to accept reality and move on.

George and Jennie nodded politely. Then they went back to searching.

A Widow’s Vigil

After George died in 1969, Jennie built a fence around their property. She added a series of rooms onto the house, extensions that made the structure sprawl in odd directions, as if she was trying to fill space that five missing children had left empty. She wore black every day for the next twenty years. Not in mourning—she never mourned—but in defiance. Black was a statement: I have not given up. I am still waiting.

She tended the memorial garden George had planted over the buried basement. Every morning, rain or shine, she walked out there with flowers. She talked to her children, told them about the family they’d missed, the grandchildren they’d never met, the life that should have been theirs.

The billboard stayed up. Weather battered it, faded the photographs, but Jennie had it repainted again and again. Drivers who took Route 16 regularly could recite the details from memory—five faces, five names, the offer of a reward, the plea for information. It became a landmark, part of the landscape, impossible to ignore.

Jennie answered every letter that came, followed every new lead no matter how implausible. Someone claimed to have seen Betty working in a diner in Ohio. Jennie got in the car and drove there. It wasn’t Betty. A woman called saying Martha was living under an assumed name in Florida. Jennie investigated. Another dead end.

Hope was a muscle she’d exercised for so long it had become involuntary. She couldn’t stop believing any more than she could stop breathing.

In 1989, Jennie Sodder died. She was ninety-one years old. She’d outlived her husband by two decades. She’d spent forty-four years—nearly half a century—searching for her children.

Only after her death did the family finally take down the billboard. It felt wrong, like giving up, like admitting defeat. But the surviving children were elderly themselves by then. They couldn’t maintain it anymore. And maybe, some of them thought, it was time to let their parents rest.

The Legacy of Unanswered Questions

Today, more than eighty years after the fire, the Sodder children case remains officially unsolved. The files sit in storage somewhere in West Virginia, yellowed and brittle, full of testimonies that contradicted each other and evidence that raised more questions than answers.

Modern investigators have looked at the case with fresh eyes, armed with forensic techniques that didn’t exist in 1945. Some have suggested DNA testing—if any distant relatives of the Sodders could be located, their DNA might be compared against unidentified remains from the era. But the Sodder house burned so completely, and the investigation was so badly botched from the start, that there’s likely nothing left to test.

The photograph sent to Jennie in 1968 remains a mystery. Was it really Louis, reaching out after decades of silence? Or was it a cruel prank, someone exploiting a mother’s grief for reasons known only to themselves? The handwriting has never been analyzed. The numbers and cryptic message have never been decoded. The man in the photograph was never identified.

Descendants of the Sodder family continue to search for answers. Jennie Henthorn, George and Jennie’s granddaughter, has kept the story alive through interviews and advocacy. She posts on social media, responds to amateur sleuths who think they’ve found new leads, shares family photographs and documents that might trigger someone’s memory.

“We just want to know what happened,” she’s said, echoing the exact words her grandfather spoke six decades ago. “That’s all we’ve ever wanted”.

The house where the fire occurred is gone now. The Sodders rebuilt on the same spot, and that structure has since been torn down too. The land is empty, just grass and trees and wind. But people in Fayetteville still know the story. They point out where the billboard used to stand on Route 16. They remember Christmas Eve 1945, even if they weren’t born yet, because stories like this don’t die. They get passed down, generation to generation, kept alive by the sheer impossibility of forgetting.

What Really Happened?

The truth is, we may never know. Every theory has holes. Every piece of evidence can be interpreted multiple ways.

Maybe the Mafia did kidnap the children, spirited them away to punish George for his defiance or his politics. Maybe they died that night, far from the fire, their bodies hidden where they’d never be found. Maybe some lived, grew up believing lies, and died old without ever knowing who they really were.

Or maybe the fire was exactly what officials claimed—a tragic accident caused by faulty wiring, made worse by equipment failures and bad luck. Maybe the heat was intense enough to cremate five children completely, physics be damned. Maybe all the strange details—the missing ladder, the dead trucks, the cut phone line—were just coincidences, the universe’s cruel way of making a tragedy feel like a conspiracy.

What we do know is this: five children disappeared on Christmas Eve 1945. Their parents spent the rest of their lives searching. A community was forever changed. And somewhere, in the space between what we believe and what we can prove, the truth waits.

Remembering the Children

Maurice Sodder would have turned ninety-three in 2024. Martha would have been ninety-one. Louis, eighty-eight. Jennie, eighty-six. Betty, eighty-three.

They would have lived through the Korean War, Vietnam, the moon landing, the fall of the Berlin Wall, 9/11, the digital revolution. They would have had children, grandchildren, maybe great-grandchildren by now. They would have voted in elections, worked jobs, fallen in love, experienced heartbreak, celebrated Christmases surrounded by family.

Instead, they remain forever young in photographs, their lives reduced to a single terrible night. They exist now only in memory and mystery, in the questions that refuse to die, in the hope that someday, somehow, someone will finally tell their story’s end.

The case has been featured in countless documentaries, true crime podcasts, and articles. It’s been dissected by amateur detectives on internet forums, analyzed by forensic experts, debated by historians. Everyone has a theory. Everyone thinks they know what happened.

But George and Jennie Sodder, who knew those children better than anyone, who loved them more fiercely than anyone could imagine, died without answers. They died still searching, still hoping, still believing against all evidence and reason that their babies were out there somewhere.

And maybe that’s the real tragedy—not what happened on Christmas Eve 1945, but what happened in all the years after. The slow, agonizing torture of not knowing. The way hope can keep you alive and kill you at the same time. The realization that some questions don’t have answers, some mysteries don’t get solved, some stories don’t get endings.

The Questions That Remain

Why did the fire chief lie about finding a heart in the ashes? What was the insurance salesman’s real connection to what happened? Who were the men seen taking children into a car the morning after the fire? Why did both of George’s trucks fail to start that night? Where did the ladder go? Who cut the phone line? What was that noise on the roof that woke Jennie?

And most importantly: Where are Maurice, Martha, Louis, Jennie, and Betty Sodder?

The FBI declined to investigate, calling it a local matter. Local police closed the case in 1950, declaring it hopeless. The state of West Virginia issued death certificates and moved on. But the family never did. The community never did. The people who drive past that empty stretch of Route 16 where the billboard once stood never did.

Because some stories demand to be remembered. Some mysteries deserve better than silence. And some families deserve answers, even if those answers come eighty years too late.

The Sodder children case is more than just an unsolved mystery. It’s a testament to the power of a parent’s love, the resilience of hope in the face of despair, and the terrible truth that sometimes the worst thing that can happen isn’t losing someone—it’s never knowing what you lost.

On Christmas Eve every year, people in Fayetteville still think about them. They imagine those five faces in the photographs, frozen in childhood, never aging, never changing. They wonder what Maurice would have looked like at fifty, what career Martha might have chosen, whether Louis grew up to look like the man in that mysterious photograph, what Jennie’s laugh sounded like, whether Betty would have had children of her own.

They wonder if, somewhere, in some small town or big city, someone is walking around with the Sodder name buried in their past, with stories their parents told them that never quite added up, with a nagging feeling that their life isn’t quite what it seems.

And they hope—just like George and Jennie Sodder hoped for forty-four years—that someday, somehow, the truth will finally come home.