The afternoon sun blazed over Immokalee, Florida, on January 10, 2009, when a little boy with bright brown eyes and a hesitant smile stepped outside to play. His name was Adji Desir, though those who loved him called him “Ji Ji”. At just six years old, standing only three feet tall and weighing forty-five pounds, Adji was smaller than most children his age. But his size wasn’t what made him vulnerable that day. It was something far more terrifying: Adji could barely speak, functioning at the mental capacity of a two-year-old, and he was deathly afraid of strangers.

Within thirty minutes of stepping outside his grandmother’s home, Adji vanished. Not a single scream. Not a single cry for help. Just gone. And sixteen years later, despite over twenty-five hundred investigated tips, massive searches spanning thousands of acres, and the deployment of more than thirteen hundred law enforcement agencies across Florida, no one knows what happened to the little boy who couldn’t speak for himself.

A Mother’s Promise, A Grandmother’s Watch

Marie Neida’s life had never been easy. She left Haiti in 2001, seeking a better future in the United States, driven by dreams of opportunity and the promise of providing a safe life for her future children. During a three-month return trip to Haiti, she became pregnant with Adji. When he was born on October 15, 2002, Marie’s heart filled with a fierce, protective love. But as Adji grew, it became clear that he faced challenges that would make his world far more complicated than most.

Adji was diagnosed with a mental disability that left him almost entirely nonverbal. While he understood Haitian Creole—the language whispered in his home, the language of his heritage—he couldn’t speak it. He couldn’t even say his own name, though somewhere deep inside, he knew it. In English, he could manage only a few scattered words. When he wanted to communicate “yes” or “no,” he would shake or nod his head, his primary bridge to the world around him. Due to his disability, experts feared that if Adji ever found himself in danger, he wouldn’t be able to ask for help.

By 2009, Marie had built a new life in Immokalee, working as a nurse and living with her husband, Antal Elant, Adji’s stepfather. Immokalee was a small agricultural community in Collier County, Florida, known for its vast tomato fields and its population of immigrant and migrant farmworker families. The town’s name itself, derived from the Mikasuki language, meant “your home”. For Marie, it was supposed to be exactly that—a safe place where Adji could grow up protected.

On that Saturday in January, Marie had to work. She dropped Adji off at his grandmother’s house in Farm Workers Village, a residential community in the 800 block of Grace Street. Farm Workers Village, built in 1999, was home to three hundred fifteen units designed to house the families who worked Immokalee’s fields. It wasn’t a gated fortress, but it was a tight-knit community where neighbors knew each other, where children played together in the yards, where watchful eyes were supposed to keep everyone safe.

Adji’s grandmother had watched him many times before. That afternoon, he ate lunch with her, then drifted in and out of the house, joining the neighborhood children who gathered outside to play in the fading winter light. It was an ordinary day. A safe day. Or so everyone thought.

Thirty Minutes to Disappear

At approximately 5:15 p.m., Adji’s grandmother looked out the window and saw him playing outside with the other children. He was wearing a blue t-shirt with thin yellow stripes, blue shorts decorated with pink flamingos down the sides, and two-tone blue sneakers that his family would later provide photos of to investigators. Everything seemed normal—kids laughing, running, living in that suspended bubble of childhood where time stretches endlessly and danger feels impossibly far away.

But sometime before 5:45 p.m., that bubble shattered.

When Adji’s stepfather arrived around 5:00 p.m. to pick him up, the family realized with growing horror that Adji was nowhere to be found. His grandmother checked the house. She called his name—though she knew he might not respond even if he heard her. She asked the other children where Adji had gone. They didn’t know. One child, Adji’s younger sister, told investigators she had been playing with him outside with several other kids before he disappeared. She said Adji walked down the street, and that was the last time anyone saw him.

Panic set in quickly. The family searched for two hours, their voices growing hoarse, their fear mounting with every passing minute. They combed through the streets of Farm Workers Village, knocked on neighbors’ doors, checked every corner where a small, frightened boy might hide. But there was nothing. No sign. No trace.

At 7:00 p.m., they called the police.

The Search That Found Nothing

The Collier County Sheriff’s Office launched an immediate and massive response. Hundreds of deputies flooded into Immokalee, joined by K-9 units, search-and-rescue teams, and volunteers from the community. They scoured thousands of acres surrounding Farm Workers Village, extending their search into the dense, wild terrain near the Florida Everglades that bordered the town. The Everglades—a vast, unforgiving wilderness where a small child could vanish without a trace among the sawgrass marshes, alligator-infested waters, and tangled vegetation.

For a week, the search continued. Investigators interviewed everyone who had been in the area that afternoon. They reviewed timelines, mapped out Adji’s last known movements, tried to piece together those fatal thirty minutes when a little boy who couldn’t call for help simply ceased to exist in the world his family knew.

But they found nothing. No clothing. No footprints. No witnesses who saw anything unusual. It was as if Adji had been plucked from the earth by invisible hands.

Marie Neida, devastated and clinging to desperate hope, told WINK News that it wasn’t like Adji to wander far from home. “God will give him back to me,” she said, her voice breaking. “I think he will come home”.

Theories, Suspicions, and Dead Ends

As the initial search yielded no results, investigators began exploring darker possibilities. Could Adji have wandered into the Everglades and become lost in its treacherous expanse? Given his mental disability and his fear of strangers, would he have run and hidden if someone tried to help him? Or had something far more sinister occurred?

One theory emerged early: that Adji had been taken to Haiti. His biological father, Yves Desir, still lived there, along with extended family members. Investigators examined this possibility thoroughly, looking for any evidence that someone had smuggled the boy out of the country and back to the Caribbean island where his mother’s journey had begun. But the investigation turned up nothing to support this theory. No suspicious travel records. No credible sightings. No proof.

Suspicion briefly turned toward the family itself, as it often does in cases of missing children. But authorities cleared Adji’s mother, stepfather, and grandmother shortly after his disappearance. There was no evidence of foul play by any family member, no signs of abuse or neglect, no motive that investigators could uncover. These were people who loved Adji, who were as desperate to find him as the strangers searching through the swamps.

The official conclusion from law enforcement was chilling in its ambiguity: Adji had either wandered away on his own or had been abducted by a non-relative. Both scenarios were nightmares. If Adji had wandered off, his inability to communicate meant he couldn’t tell anyone who he was or where he came from, even if someone kind found him. If he had been taken, his silence made him the perfect victim—a child who couldn’t scream, couldn’t identify his abductor, couldn’t ask for help.

A Family’s Grief, A Community’s Memory

The years passed with excruciating slowness for Marie Neida. She and her husband had another daughter, whom they named Adjiani—a living tribute to the brother who never came home. Adji’s grandmother moved out of Farm Workers Village, unable to bear living in the place where her grandson had vanished, and now shares a home with Marie and Antal.

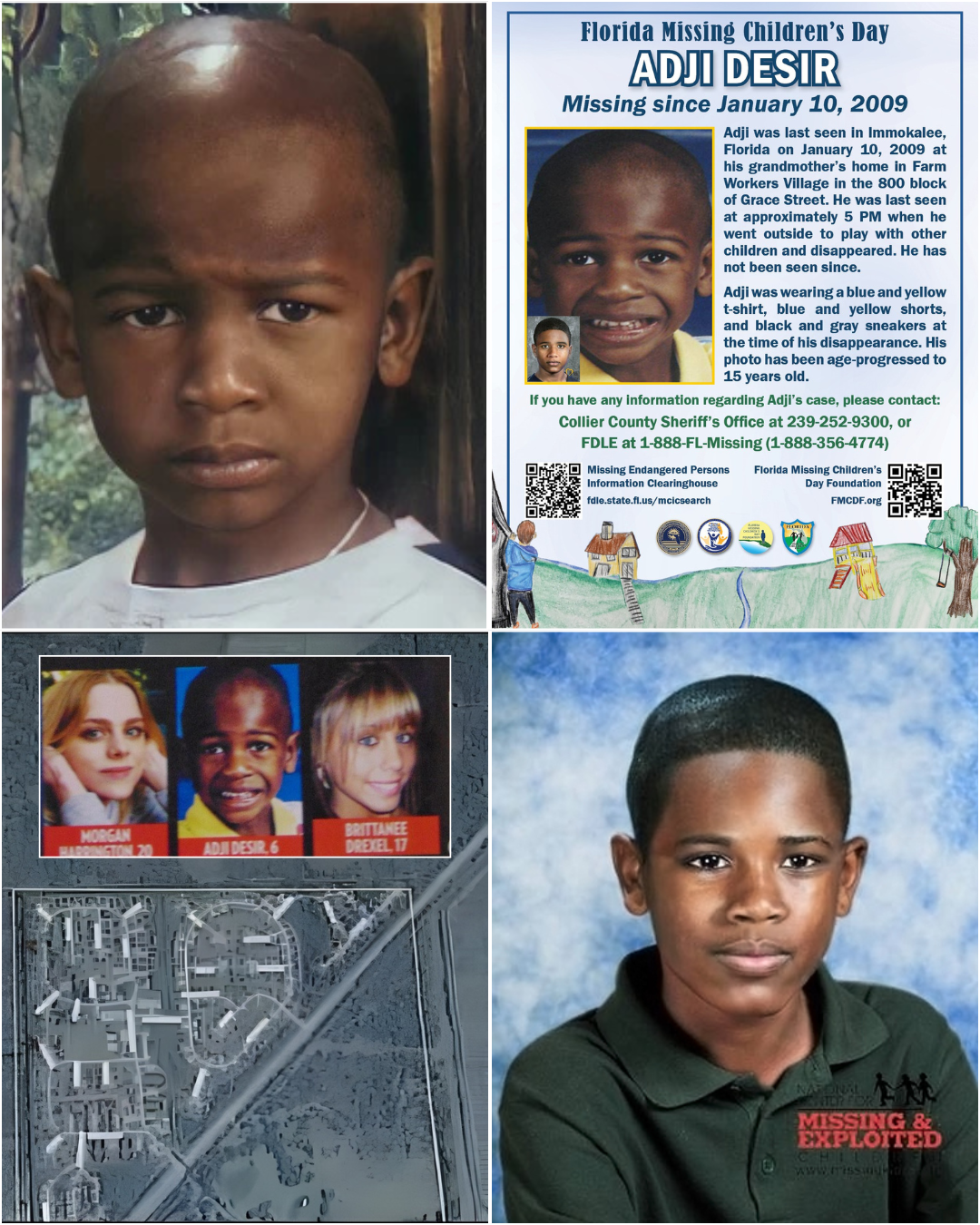

Every birthday that passed without Adji was another wound. Every January 10th marked another anniversary of that terrible afternoon when thirty minutes changed everything. The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children created age-progression images showing what Adji might look like at fifteen, then older. The photos show a young man with Adji’s eyes, imagining a future that may never exist.

Over the years, more than thirteen hundred law enforcement agencies have been deployed throughout Florida to search for any trace of Adji Desir. Seven hundred Collier County Sheriff’s Office deputies alone have worked on the case. Twenty-five hundred tips have been investigated and completed. Each one brought a flicker of hope. Each one ended in disappointment.

Then, in 2023, something happened that sent shockwaves through the investigation.

A Voice from Texas

Fourteen years after Adji vanished, authorities received a tip that the boy—now a young man of twenty-one—had been spotted in Midland, Texas. Someone claimed they had seen him, that he matched the description, that after all this time, Adji Desir might still be alive.

Investigators rushed to Texas. Hope, that dangerous and necessary thing, surged through everyone connected to the case. Could it really be him? Could a child who disappeared without a trace have survived, grown up, and somehow ended up over a thousand miles away from where he was last seen?

But the claim turned out to be negative. It wasn’t Adji. Just another ghost. Another dead end.

The disappointment was crushing. And yet, the tip raised haunting questions that still linger today. If Adji was taken, could he still be out there somewhere? At twenty-three years old now, would he have any memory of his life before that January afternoon? With his mental disability and his inability to speak, would he even know his real name if someone said it to him?

These are the questions that torment Marie Neida when she lies awake at night. These are the nightmares that have no resolution.

What the Silence Hides

The most terrifying aspect of Adji Desir’s disappearance isn’t just that he vanished—it’s that his disability made him uniquely vulnerable in ways most people can’t fully comprehend. A six-year-old child who could barely speak, who couldn’t say his own name, who was afraid of strangers and would likely hide rather than seek help.

If someone took Adji, his silence would have made him the perfect victim. He couldn’t scream for his mother. He couldn’t tell anyone who his family was or where he came from. He couldn’t describe his abductor or ask a passerby for help. Even if someone genuinely tried to help him, his fear of strangers might have made him run and hide.

If Adji wandered off and got lost, the outcome would have been just as tragic. Unable to communicate with anyone who found him, unable to explain that he had a mother who loved him and a home he came from, Adji could have ended up in a system that had no way of identifying him. He could have been placed in foster care or an institution under a different name, forever separated from the family desperately searching for him.

And if the worst happened—if Adji didn’t survive that day—his inability to cry out might mean that no one heard him in his final moments.

Immokalee Remembers

Immokalee, Florida, has never forgotten Adji Desir. In June 2025, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement posted on social media: “Where is he? Over 16 years ago, 6-year-old Adji Desir went missing after he went outside to play with other kids on January 10, 2009, in Immokalee”. The post was a reminder that this case remains open, that authorities haven’t given up, that somewhere, someone might know something.

Farm Workers Village, where Adji disappeared, still stands on Grace Street. Children still play in its yards, just as they did that Saturday in 2009. But the community remembers the little boy with the yellow-striped shirt and the flamingo shorts who walked down the street one afternoon and never came back.

Sergeant Raul Roman of the Collier County Sheriff’s Office, who has worked extensively on the case, told reporters that the search continues. Every tip is still investigated. Every lead, no matter how unlikely, is still pursued. Because until they find Adji—or find out what happened to him—this case will never truly be closed.

The Boy Who Couldn’t Speak

What makes Adji Desir’s case so haunting isn’t just the mystery of his disappearance. It’s the knowledge that a child who already faced such profound challenges in communicating with the world became even more invisible when he needed to be seen most. It’s the thirty-minute window that changed everything, leaving behind only questions and grief.

It’s the image of a three-foot-tall boy in two-tone blue sneakers, walking down a street in a Florida farmworker village, heading toward a fate that no one has ever been able to uncover.

In the files of the Collier County Sheriff’s Office, Adji’s case number is 09-942. His NCMEC case number is 1113684. His NamUs case number is 3878. These numbers represent thousands of hours of investigation, heartbreak measured in years, and a family’s unending vigil.

Marie Neida’s daughter Adjiani is now a teenager, growing up in the shadow of an older brother she never knew. Does she wonder what Adji would have been like if he were still here? Does she dream of the impossible reunion, the brother who walks through the door after all these years and finally comes home?

Adji Desir would be twenty-three years old now. If he’s still alive, he’s a grown man—though his mental disability means he likely still functions at the level of a young child. He might have no idea who he really is, where he came from, or that thousands of people have been searching for him for more than half his life.

Or he might be gone entirely, his story ended in those thirty minutes back in 2009, his fate known only to whatever darkness swallowed him that day.

Sixteen Years of Silence

On January 10, 2025, it will be sixteen years since Adji Desir disappeared. Sixteen years since he walked outside to play and never came home. Sixteen years since a family was shattered by thirty minutes they can never get back.

The Collier County Sheriff’s Office continues to ask anyone with information about Adji’s whereabouts to call them at (239) 793-9300. They still believe someone out there knows something—saw something, heard something, or has kept a terrible secret for far too long.

Because somewhere, in the heart of Florida or perhaps far beyond it, there might be answers. There might be a young man who doesn’t know his real name is Adji Desir, who doesn’t know his mother never stopped looking for him, who doesn’t know that he was loved fiercely before he vanished and has been loved fiercely every day since.

Or there might only be silence—the same silence that defined Adji’s short life, the same silence that has defined this case for sixteen years.

The boy who couldn’t speak still can’t tell us what happened to him. And until someone breaks that silence, his disappearance will remain one of Florida’s most heartbreaking unsolved mysteries—a little boy in flamingo shorts who walked into the late afternoon and disappeared from the world entirely, leaving behind only questions, grief, and the desperate hope that someday, somehow, the truth will finally be found.

Author’s Note: Adji Desir’s case remains unsolved and actively investigated by the Collier County Sheriff’s Office. If you have any information regarding his disappearance or current whereabouts, please contact the Collier County Sheriff’s Office at (239) 793-9300 or the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children at 1-800-THE-LOST (1-800-843-5678). Every tip matters. Every piece of information could be the one that brings Adji home.

The Community That Couldn’t Forget

Farm Workers Village wasn’t just a collection of apartments—it was a lifeline for families like Marie Neida’s. Built in 1999 by the Collier County Housing Authority, the community provided affordable housing for the agricultural workers who kept Immokalee’s economy alive. Three hundred fifteen units spread across the development, home to families who worked from sunrise to sunset in the tomato fields, the orange groves, the vegetable farms that stretched for miles beyond the town’s borders.

These were tight-knit families, many of them immigrants from Haiti, Mexico, and Central America, who understood the value of community and the necessity of watching out for each other’s children. In a place like Farm Workers Village, everyone knew everyone. Children played together while parents worked grueling shifts. Neighbors looked out their windows and kept an eye on the kids running through the streets.

That’s what made Adji’s disappearance so incomprehensible. How does a six-year-old boy vanish in broad daylight from a community where watchful eyes were everywhere? How does a child disappear in thirty minutes without anyone seeing anything, hearing anything, noticing anything wrong?

The truth, investigators would later realize, was that those thirty minutes created the perfect storm of vulnerability. It was late afternoon on a Saturday—a time when parents were coming home from work, when families were transitioning between day and evening routines. It was that liminal hour when attention fragments, when the collective vigilance of a community has natural gaps. Children were playing outside, but supervision was diffused among multiple adults, each assuming someone else was watching.

And Adji, with his mental disability and his inability to call out, could have been led away or wandered off without making a single sound to alert anyone.

The Investigation Deepens

As days turned into weeks, the Collier County Sheriff’s Office faced a mystery with almost no physical evidence. There were no witnesses to an abduction. No signs of a struggle. No vehicle seen speeding away from Farm Workers Village with a small boy inside. The K-9 units that searched thousands of acres surrounding Immokalee found no scent trail leading into the Everglades. It was as if Adji had simply ceased to exist the moment he walked down Grace Street.

Investigators conducted extensive interviews with everyone in the neighborhood. They spoke to the children who had been playing outside with Adji that afternoon, trying to extract memories from young minds about what they had seen. Adji’s younger sister, who had been playing with him shortly before he vanished, told them she saw him walk down the street—and then he was gone. But where had he gone? Why had he gone? What had drawn him away from the safety of the other children?

These questions had no answers.

The investigation also examined Adji’s family history with microscopic intensity. Marie Neida’s journey from Haiti to the United States was documented and analyzed. Her relationship with Adji’s biological father, Yves Desir, who remained in Haiti, was scrutinized for any possible motive or connection to the disappearance. Investigators looked at her marriage to Antal Elant, searching for any signs of domestic issues that might have played a role.

They found nothing. Marie was a dedicated mother who worked hard to provide for her children. Antal was a supportive stepfather. Adji’s grandmother, who had been watching him that day, was devastated by his disappearance and cooperated fully with authorities. There was no evidence of abuse, no financial motive, no custody dispute that would explain why anyone in the family would want to harm Adji or make him disappear.

CNN covered the case extensively, with Nancy Grace featuring Adji’s disappearance on her show in March 2011, more than two years after he vanished. Speaking to viewers, she emphasized the heartbreak of the case: a nonverbal child who couldn’t ask for help, a family desperate for answers, and a complete absence of clues about what had happened.

The Haiti Theory

Despite the lack of evidence, the theory that Adji had been taken to Haiti persisted for years. It made a certain terrible logic: Haiti was where Adji’s roots were, where his biological father lived, where extended family members might have had their own ideas about where the boy should be raised.

But investigators who pursued this angle found themselves facing dead ends at every turn. There were no records of Adji being taken out of the United States through any legal channels. No passport had been issued in his name after January 10, 2009. No one reported seeing Marie Neida or any family member traveling with a small child matching Adji’s description in the days and weeks after his disappearance.

Could Adji have been smuggled out of the country illegally? It was possible, investigators acknowledged, but extraordinarily difficult to prove or disprove. The U.S.-Haiti corridor had been used for human trafficking before, but those cases typically involved older children or adults. Moving a six-year-old child with a severe mental disability across international borders would have required careful planning, multiple co-conspirators, and a level of organization that didn’t fit the profile of Adji’s family or their circumstances.

Moreover, Yves Desir, Adji’s biological father, was cooperative with investigators and expressed genuine shock and grief when informed of his son’s disappearance. There was no evidence that he had orchestrated any kind of kidnapping or that he had any contact with Adji in the years since Marie had left Haiti.

As the months and years passed, the Haiti theory gradually faded from the forefront of the investigation, though it was never completely discarded. Somewhere in the files of the Collier County Sheriff’s Office, it remained a possibility—remote, unproven, but never entirely dismissed.

The Everglades Hypothesis

The other major theory investigators explored was even darker: that Adji had wandered into the Everglades and perished there. Immokalee sits on the northern edge of the vast wilderness area known as the Big Cypress National Preserve, which is part of the greater Everglades ecosystem. The landscape is unforgiving—sawgrass marshes that stretch to the horizon, cypress swamps thick with vegetation, and waterways teeming with alligators and other predators.

For a small child, especially one with Adji’s mental disability and fear of strangers, the Everglades would have been a death trap. If he had wandered away from Farm Workers Village and somehow made it to the wild areas beyond the town, he would have been facing dozens of lethal dangers. Alligators that could strike without warning. Venomous snakes hidden in the grass. Deep water channels where a three-foot-tall boy could drown in seconds. Exposure to the elements in a subtropical climate that could be brutally hot during the day and surprisingly cold at night in January.

Search teams combed thousands of acres of wilderness surrounding Immokalee in the days and weeks after Adji’s disappearance. They used helicopters, all-terrain vehicles, boats, and tracking dogs. They searched through areas so dense and difficult to navigate that experienced outdoorsmen struggled to move through them.

They found nothing. No clothing. No remains. No sign that Adji had ever been there.

This absence of evidence was both hopeful and terrifying. Hopeful because it meant Adji might not have died in the wilderness. Terrifying because if he wasn’t in the Everglades, then where was he?

The Predator Possibility

The theory that haunted investigators most—and that they were most reluctant to discuss publicly—was that Adji had been abducted by a predator. The statistics were grim: children with developmental disabilities are seven times more likely to be victims of abuse than their neurotypical peers. A nonverbal child who couldn’t identify an abductor, couldn’t call for help, and would likely be too afraid to approach strangers for assistance would be a predator’s ideal victim.

Immokalee in 2009 was a community with its share of problems. As an agricultural town heavily dependent on migrant labor, it had a transient population—people who came and went with the seasons, workers who might spend a few months in the area before moving on to the next harvest. This created a situation where a stranger could enter the community, commit a crime, and disappear without leaving much of a trace.

Investigators looked at registered sex offenders living in and around Immokalee at the time of Adji’s disappearance. They interviewed individuals with histories of crimes against children. They examined anyone who had been in the area that day who might have had the opportunity to take Adji.

Again, they found nothing conclusive. No suspect emerged. No evidence pointed to any specific individual. The predator, if there was one, had been extraordinarily careful—or extraordinarily lucky.

A Mother’s Endless Vigil

For Marie Neida, the years since Adji’s disappearance have been an exercise in sustained grief punctuated by moments of desperate hope. She moved out of the apartment where she had lived when Adji was taken, unable to bear the memories. Her mother, Adji’s grandmother, also left Farm Workers Village, and the two women now live together with Marie’s husband and their daughter Adjiani.

Every year on Adji’s birthday, October 15, Marie marks the passage of another year without her son. Every January 10, she relives the nightmare of the day he disappeared. The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children has created multiple age-progression images of Adji, showing what he might look like at different ages. Marie keeps these images close, studying them, trying to recognize her son in the face of a teenager, then a young adult, imagining futures that may never exist.

The decision to name her younger daughter Adjiani was both a tribute and a prayer. The name keeps Adji’s memory alive in the family, ensures that his existence isn’t forgotten, that the hole he left behind is acknowledged every time Marie calls her daughter’s name. But it’s also a kind of magical thinking—a belief that by honoring Adji, by keeping him present in their lives, somehow the universe might return him to them.

Marie has participated in numerous media appeals over the years, appearing on local news broadcasts and national television programs, holding up photos of Adji and begging anyone with information to come forward. Her pain is raw and undimmed by time. In every interview, she expresses the same desperate hope: that Adji is still alive somewhere, that he will be found, that God will bring him back to her.

“I think he will come home,” she told reporters in those early days after his disappearance. Sixteen years later, she still believes it.

The Tips That Led Nowhere

Over twenty-five hundred tips have been called in to the Collier County Sheriff’s Office regarding Adji Desir. Twenty-five hundred potential leads, each one investigated and documented, each one carrying the possibility of being the breakthrough that solves the case.

Some tips were well-intentioned but vague—people who thought they might have seen a child resembling Adji years ago but couldn’t remember exactly where or when. Some were based on age-progression images, with callers reporting that they had seen a teenager or young adult who looked like the digitally created photos. Some came from psychics claiming to have visions about what happened to Adji, describing locations where his body might be found or scenarios about his fate.

Each tip, no matter how unlikely, was followed up. Investigators traveled to different parts of Florida, chasing sightings that turned out to be other children. They dug in locations suggested by psychics, finding nothing. They interviewed people who called in with theories, trying to separate genuine information from well-meaning speculation.

The frustration of this process—the endless cycle of hope and disappointment—took its toll on everyone involved. For the investigators, it meant years of following leads that went nowhere. For Marie Neida, every phone call from the sheriff’s office sent her heart racing, wondering if this was finally the call that would bring news of her son.

But the news never came. The tips, for all their volume, yielded nothing substantial. Adji remained missing, his fate unknown.

The 2023 Texas Sighting

Then came 2023, fourteen years after Adji’s disappearance, and a tip that seemed different from all the others. Someone in Midland, Texas—more than a thousand miles from Immokalee—claimed to have seen a young man who matched Adji’s description and age progression.

The tip was specific enough to warrant serious investigation. Midland is a mid-sized city in West Texas, in the heart of the Permian Basin oil country. It’s not the kind of place one would automatically associate with a missing child from Florida. But that randomness actually lent the tip a certain credibility—it wasn’t following an obvious narrative, wasn’t trying too hard to connect dots.

Investigators responded immediately. The possibility that Adji could have survived, could have been taken to Texas, could still be alive as a twenty-one-year-old young man, was too important to ignore. If there was even a chance it was him, they had to pursue it.

The investigation was thorough. Authorities in Texas cooperated with Florida law enforcement, tracking down the individual who had been reported as possibly being Adji. They compared physical characteristics, looked for any identifying marks or features, tried to determine if this young man in Texas could be the little boy who had vanished from Farm Workers Village so many years ago.

But in the end, it wasn’t him. The young man in Texas was someone else entirely. Another dead end. Another crushing disappointment.

Still, the Texas tip raised haunting questions that investigators and the family continue to grapple with. If Adji was abducted, could he have been taken far from Florida? Given his mental disability and inability to communicate, could he be living somewhere under a different identity, completely unaware of who he really is or that people are searching for him? Could he have been integrated into another family, perhaps told a different story about his origins, unable to contradict it because he can’t speak?

These scenarios, while heartbreaking, at least offered the possibility that Adji was alive. And for Marie Neida, that possibility—no matter how remote—was better than the alternative.

The Silence That Speaks Volumes

What makes Adji Desir’s case profoundly different from other missing children cases is the cruel intersection of his disability and his disappearance. Most missing children, if they’re found alive, can eventually tell their story—where they were taken, who took them, what happened to them. They can identify themselves to authorities, ask for help from strangers, or find ways to escape and return home.

Adji couldn’t do any of those things. His mental disability left him functioning at the level of a two-year-old in a six-year-old’s body. He couldn’t say his own name. He couldn’t tell anyone where he lived or who his mother was. The few English words he knew weren’t enough to communicate danger or ask for rescue. And his understanding of Haitian Creole, while better than his English, didn’t translate into the ability to speak it.

This meant that if someone took Adji with the intention of keeping him, they had the perfect victim. A child who couldn’t identify them to police. A child who couldn’t describe where he came from or call out his real name. A child who, because of his fear of strangers, might actually hide or run away from people trying to help him.

It also meant that if Adji simply wandered away and became lost, the consequences would be equally tragic. Any Good Samaritan who found him would have no way of knowing who he was. Even if they took him to police or a hospital, Adji couldn’t provide the information needed to reunite him with his family. He could have ended up in the foster care system, in a group home for children with disabilities, or in any number of institutional settings under a different identity, forever separated from the mother desperately searching for him.

The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children has documented numerous cases of missing children with disabilities, and the statistics are sobering. These children are more likely to be victimized, less likely to be able to seek help, and more likely to have their disappearances dismissed as runaways or wandering incidents rather than potential abductions. Adji’s case embodied all of these tragic realities.

The Investigators Who Won’t Quit

Sergeant Raul Roman of the Collier County Sheriff’s Office has become one of the public faces of the ongoing investigation into Adji’s disappearance. In interviews over the years, he has emphasized that the case remains active, that every tip is still taken seriously, and that the Sheriff’s Office is committed to finding answers no matter how much time has passed.

“We haven’t given up,” Roman told reporters on one of the many anniversaries of Adji’s disappearance. “Every piece of information we receive is investigated thoroughly”.

The scope of the investigation has been staggering. More than thirteen hundred law enforcement agencies across Florida have been involved in the search for Adji at various points over the past sixteen years. Seven hundred Collier County Sheriff’s deputies alone have worked on the case in some capacity. The man-hours devoted to searching, interviewing, analyzing evidence, and following up on tips number in the tens of thousands.

Yet for all this effort, the fundamental mystery remains unsolved. The evidence—or lack thereof—hasn’t changed since those first desperate days in January 2009. There are still no witnesses to an abduction. No physical evidence of what happened to Adji. No confession from anyone involved in his disappearance. Just a three-foot-tall boy in flamingo-decorated shorts who walked down a street and vanished into thin air.

The Florida Department of Law Enforcement continues to publicize the case, posting about Adji on social media and asking the public for help. In June 2025, they shared his story again, reminding people that this case is far from forgotten, that somewhere out there, someone might know something that could finally break this case open.

What Psychology Tells Us

Experts in child development and trauma have weighed in on Adji’s case over the years, offering insights into what might have happened and what his life might be like now if he’s still alive. Dr. Mary Pulido, a psychologist specializing in missing children with disabilities, explained in a 2011 interview that children like Adji face unique challenges that make them especially vulnerable.

“A child who can’t communicate is a child who can’t advocate for themselves,” Dr. Pulido explained. “They can’t tell you they’re in danger. They can’t tell you they need help. And in many cases, they can’t even tell you their own name”.

This vulnerability extends beyond the moment of disappearance. If Adji is alive today at age twenty-three, his mental disability would likely mean he still functions at a very young developmental level. He might have no clear memories of his life before January 10, 2009. The trauma of whatever happened to him—whether abduction, becoming lost, or something else—could have further impacted his already-limited cognitive abilities.

If someone took Adji and raised him as their own child, he might have accepted whatever story they told him about his origins, unable to question or verify it. He might think of his abductor as his parent, completely unaware that a mother in Florida has never stopped searching for him.

This possibility—that Adji could be alive but completely unaware of his true identity—is perhaps the most heartbreaking scenario of all. It means he could be out there somewhere, living a life, while Marie Neida grieves the son she lost. Two parallel realities existing simultaneously, never intersecting, separated by silence and unknowing.

The Community That Changed

Immokalee has changed in the sixteen years since Adji disappeared. The farmworker community continues to grow and evolve, shaped by economic pressures, immigration policies, and the constant ebb and flow of people who come to work the fields. Farm Workers Village still stands, still houses families, still sees children playing in its streets.

But the collective memory of Adji Desir lingers. Parents who lived in Immokalee in 2009 tell their children about the little boy who vanished, using his story as a cautionary tale about staying close to home, about not talking to strangers, about how quickly safety can turn to danger. Newer residents learn about Adji from neighbors, from local news coverage on anniversaries of his disappearance, from the occasional poster or flyer that still circulates asking for information.

The case has had a lasting impact on how the Collier County Sheriff’s Office handles missing children cases, particularly those involving children with disabilities. The lessons learned from the massive search effort—what worked, what didn’t, what might have been done differently—have informed protocols and training for years afterward.

But perhaps the most significant change has been in awareness. Adji’s disappearance highlighted just how vulnerable children with developmental disabilities are and how important it is for communities to have systems in place to protect them. It sparked conversations about supervision, about neighborhood watch programs, about the specific needs of children who can’t speak for themselves.

These are important conversations, necessary conversations. But they came at a terrible price—the loss of a six-year-old boy who deserved protection and got none.

The Age Progression Images

The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children has created several age-progression images of Adji over the years, using forensic artistry and computer modeling to predict what he might look like as he ages. These images show a progression from the six-year-old boy with round cheeks and bright eyes to a teenager, and eventually to a young man in his early twenties.

Each new age progression is shared widely—posted on social media, distributed to law enforcement agencies, featured in media coverage of the case. The hope is that someone, somewhere, will see the image and recognize it as someone they know. A neighbor. A coworker. A person they’ve seen in their community who doesn’t quite fit, who seems to have a disability, who might match the description of the boy who went missing from Florida sixteen years ago.

But age progression has its limitations. It can predict general facial structure, the likely shape of features as a person matures, but it can’t account for environmental factors—how someone styles their hair, whether they have facial hair, how life experiences might have changed their appearance. And for someone like Adji, whose disability might affect how he presents himself to the world, the age progressions are educated guesses at best.

Still, Marie Neida treasures these images. They’re the only photographs she has of what her son might look like now. When she imagines Adji as a young man, these are the faces she sees. She studies them, looking for traces of the little boy she knew, trying to find her son in the features of a stranger’s face.

The Questions That Haunt the Night

There are questions about Adji Desir’s case that may never be answered. Questions that investigators have grappled with for sixteen years, that Marie Neida asks herself every day, that haunt everyone who has followed this story.

If Adji wandered off, why did the search dogs find no scent trail? If he went into the Everglades, why was no trace of him ever found despite extensive searches? If someone took him, how did they do it so quickly and quietly that no one saw anything? If he was taken to Haiti, how was it accomplished without leaving any evidence? If he’s still alive, why hasn’t anyone recognized him from the age-progression images or the thousands of missing persons reports?

These questions multiply and compound, creating a labyrinth of possibilities with no clear path to the truth. Every answer generates new questions. Every theory has gaps that can’t be filled. And at the center of this labyrinth is a little boy who couldn’t speak, couldn’t ask for help, couldn’t tell anyone what happened to him.

The most haunting question of all might be this: If Adji is alive somewhere, does he remember? Does some part of him recall a mother who loved him, a home he came from, a life before whatever happened on January 10, 2009? Or has that all been erased, leaving him a blank slate, forever disconnected from the family that grieves for him?

Marie’s Unending Hope

Marie Neida is now sixteen years older than she was when she last saw her son. She has raised another daughter, Adjiani, in Adji’s shadow. She has endured sixteen birthdays without him, sixteen Christmases with an empty place at the table, sixteen years of wondering and hoping and grieving.

In interviews, she still speaks of Adji in the present tense. Not “he was” but “he is”. Not “I loved him” but “I love him”. For Marie, Adji is not a memory of the past but an ongoing presence, a missing piece that must someday be found and returned to where it belongs.

“God will give him back to me,” she said in those early days, and she has never stopped believing it. This faith—whether based in religion, denial, or simply the fierce love of a mother who refuses to give up—has sustained her through years that would have broken many people.

Her life now revolves around the possibility of Adji’s return. She answers every call from the Sheriff’s Office, no matter how many times it’s been a false alarm. She participates in media appeals, knowing that the next interview could be the one that reaches someone who knows something. She keeps his memory alive in her home, in conversations with her daughter, in the way she moves through the world always watching, always hoping to see a familiar face in a crowd.

This is what it means to be the parent of a missing child—to live in a permanent state of suspended grief, unable to fully mourn because death hasn’t been confirmed, unable to fully hope because so much time has passed. It’s a unique form of torture, and Marie Neida has endured it for sixteen years.

The Case That Won’t Close

As of November 2025, Adji Desir’s case remains open and active with the Collier County Sheriff’s Office. It’s case number 09-942 in their files, but it’s far more than just a number. It represents one of the most baffling missing persons cases in Florida history, a disappearance that defies explanation and resists resolution.

The Sheriff’s Office continues to maintain a dedicated tip line for any information about Adji. They still follow up on every credible lead, no matter how many years have passed. The investigation has evolved over time—different detectives have worked on it, new technologies have been applied to old evidence, fresh eyes have reviewed the case files looking for something that earlier investigators might have missed.

But the fundamental facts haven’t changed. A six-year-old boy with a severe speech disability left his grandmother’s house on a Saturday afternoon in January 2009. He was seen playing with other children around 5:15 p.m.. By 5:45 p.m., he was gone. And in the sixteen years since, despite one of the most extensive missing persons investigations in Florida history, no one has been able to definitively say what happened to him.

The case file is massive—thousands of pages of interviews, search reports, tip follow-ups, and investigative notes. It represents countless hours of work by dedicated law enforcement professionals who want nothing more than to give Marie Neida the answers she deserves. But answers, it seems, are in short supply.

A Mystery Without Resolution

Sixteen years is a long time to wait for answers that may never come. Long enough for a six-year-old boy to become a twenty-three-year-old man—if he’s still alive. Long enough for hope to dim, for leads to dry up, for the world to largely forget about the little boy in the flamingo shorts who vanished from Immokalee.

But Marie Neida hasn’t forgotten. The Collier County Sheriff’s Office hasn’t forgotten. And the people of Immokalee, many of whom still remember that terrible day in 2009, haven’t forgotten either.

Somewhere in the world, there might be a young man who doesn’t know his name is Adji Desir. Or there might be someone who knows exactly what happened on January 10, 2009, and has kept that terrible secret for sixteen years. Or the truth might be buried somewhere in the Florida wilderness, lost forever to the passage of time and the reclamation of nature.

Until answers are found, Adji’s case will remain what it has been for sixteen years—a heartbreaking mystery, a family’s unending nightmare, and a stark reminder of how vulnerable the most innocent among us can be.

The boy who couldn’t speak still can’t tell us what happened. His silence, which made him so vulnerable in life, continues to be the defining feature of his case in death or disappearance. And that silence—profound, complete, and utterly heartbreaking—may be the only answer we ever get.

If You Know Anything

Adji Desir would be twenty-three years old today. He is African-American, was three feet tall and forty-five pounds when he disappeared, with black hair and brown eyes. He has a scar on his left leg. Due to his mental disability, he functions at a much younger developmental level and is nonverbal or nearly nonverbal.

If you have any information about Adji’s disappearance or current whereabouts, please contact the Collier County Sheriff’s Office at (239) 793-9300. You can also reach the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children at 1-800-THE-LOST (1-800-843-5678).

Every piece of information matters. Every tip could be the one that finally brings Adji home. Sixteen years of silence is long enough. It’s time for someone to speak.